Inspiring dreams with embroidery

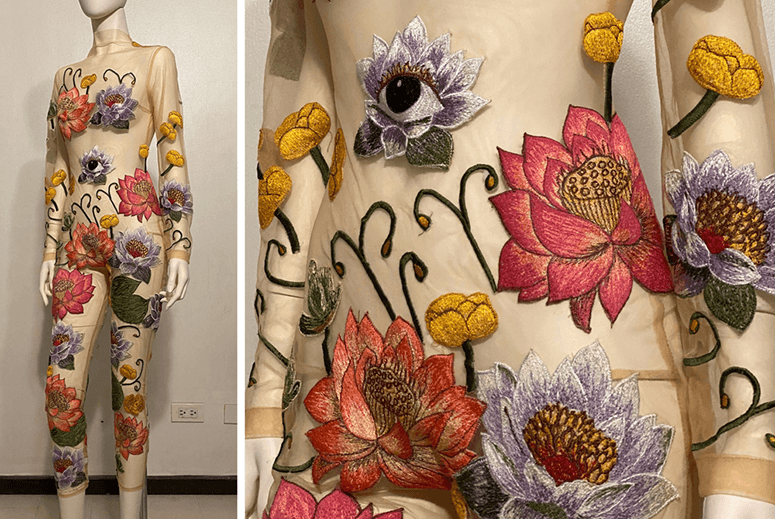

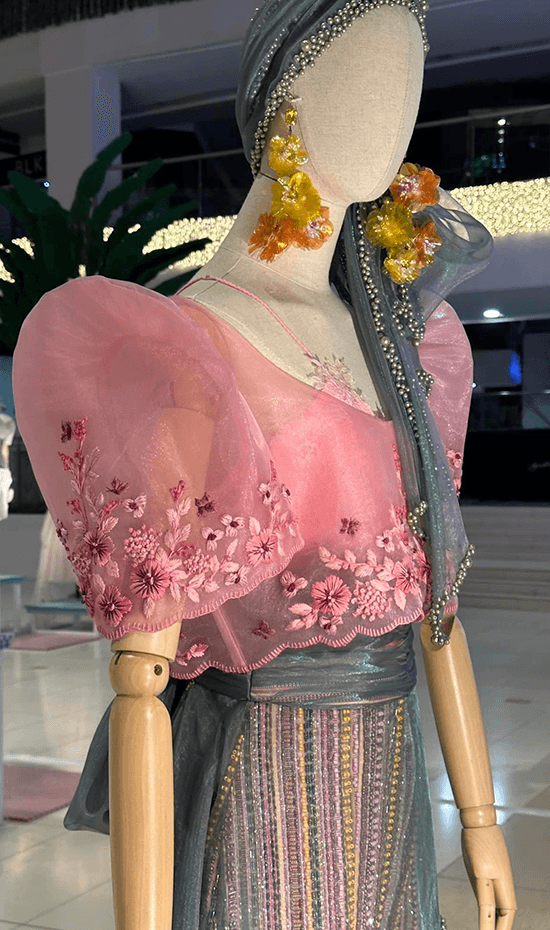

Viewing the Ternocon exhibit recently at Glorietta, we realized that one thing all the winners of this year’s edition share is the use of burda or embroidery which no doubt made their pieces look special because of the time and care taken in creating surface decoration that adds another dimension to an otherwise flat print.

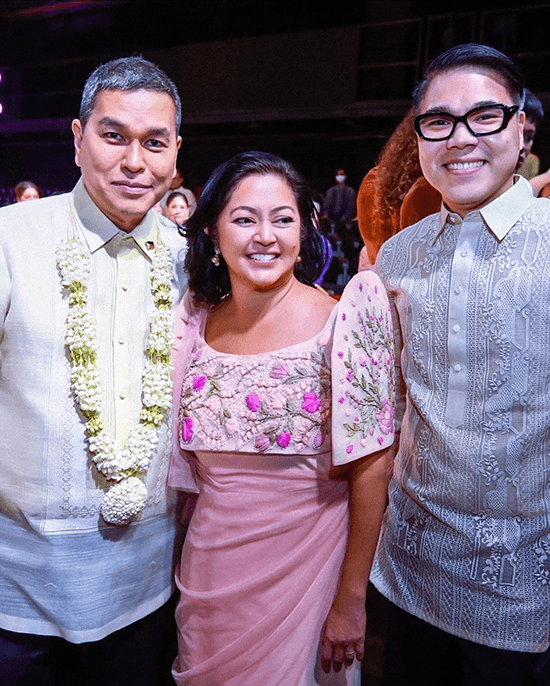

Yssa Inumerable, who got the top Pacita Longos Award, turned to her ancestral town’s famed artisans of burdang Taal to create lively florals pulsating from the boleros of her balintawaks. Pura Escurdia awardee Gabbie Sarenas had delicate sampaguita buds strewn about her versatile separates. Glady Rose Pantua, Ramon Valera awardee, who always admired her lola’s embroidered pieces in Zamboanga made it the centerpiece of her winning balintawaks that she lovingly embroidered with pink flowers in one and symbols of Philippines culture in another.

Embroidery is one of our most revered crafts, after all, with indigenous traditions from the Itneg of Abra in the north to the Mandayas and T’bolis in Mindanao as well as the Taal and Lumban embroiderers of the barong. Some of the most exquisite examples can be found in the great museums of the world—from the Victoria & Albert Museum in London to the Metropolitan Museum in New York. When we designed the Philippine Pavilion for the Canadian National Exposition and borrowed pieces from the Royal Ontario Museum, the curators showed us some of their most precious collections of Philippine weaves and embroideries which were not even on display but protected in vaults.

The need to adorn fabrics can actually be traced back to Cro-Magnon era or 30,000 BC as revealed by fossilized remains of hand-stitched and decorated clothing at a recent archaeological find. The earliest surviving embroideries are Scythian, dated between the 5th and 3rd centuries BC. From around 330 to the 15th c., Byzantium produced embroideries ornamented with gold. Chinese embroideries have been excavated, dating from the T’ang Dynasty (618-907 AD), but the most famous extant specimens are the imperial silk robes of the Ch’ing Dynasty (1644-1911/12).

By 1500 AD, embroideries had become more lavish in Europe as well as other areas of the world. This was passed on to the Philippines during the Spanish colonial era when it became a much-valued skill. In Lumban, Laguna, the beginnings of their craft can be traced to the arrival of the Spanish missionaries, with some designs dating back to the 1600s.

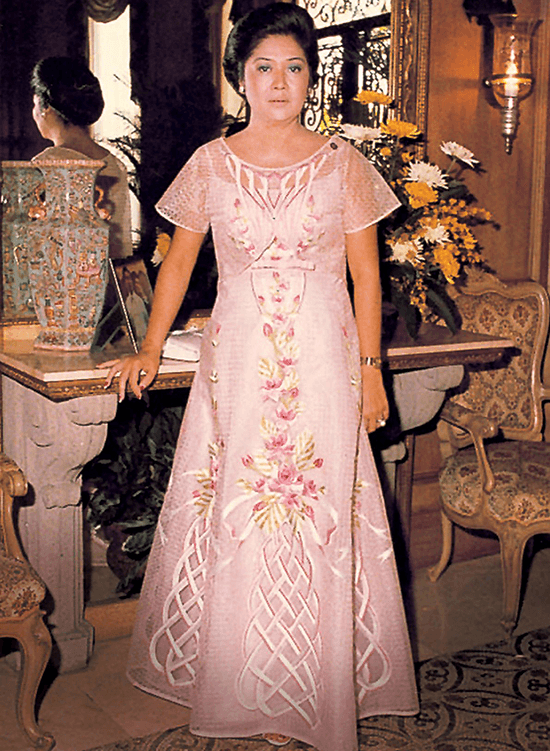

Needlework was taught to the community to keep housewives busy during their spare time and also to girls in religious houses and schools. Their work is prized for the intricate designs as well as the calado latticework which is done on piña and jusi to be made into barongs and ternos. The home-based industry reached its peak in the 1970s when the embroidered barong was the prescribed outfit of government officials attending formal functions during the administration of President Ferdinand Marcos. Their wives and other society ladies would also follow the lead of First Lady Imelda Marcos who wore ternos with hand embroidery designed by Christian Espiritu and later Joe Salazar.

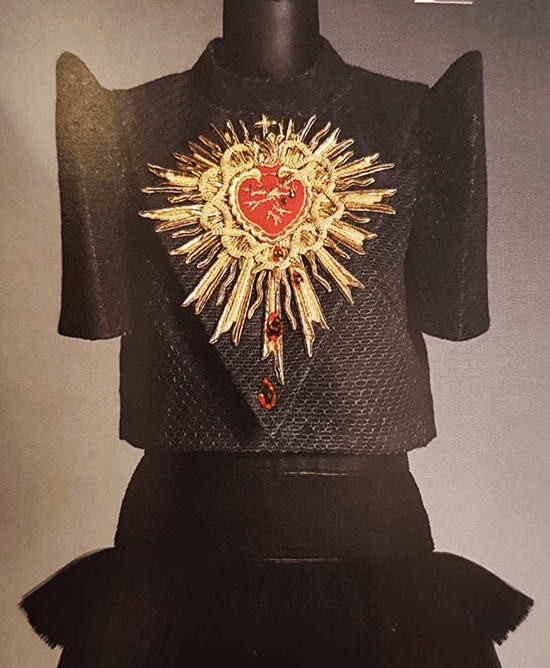

Another type of embroidery inherited from Spanish colonial times is the high-relief embroidery using gold bullion thread to adorn vestments of santos with floral and plant motifs. Known as inuod from the Tagalog word for worm, the painstaking and costly craft is practiced to this day with ateliers such as Bordados de Manila of the actor Arnold Reyes who was fascinated with the garments of the santos as a child. Collaborating with the artist Rafael del Casal who designs the patterns and the bordadora Zeny Mataya, they work on pieces that have dressed the La Naval de Manila which took nine months to create, as well as the Santo Niño de Pandacan that was sent to the Vatican. For Ternocon 2, Philip Rodriguez commissioned the atelier to execute the scapulars and other embellishments for his ternos.

In Paris, haute couture could not survive for the past century without François Lesage of the city’s oldest embroidery atelier, Maison Lesage. Originally Michonet, founded in 1858, before François’ parents took over in 1924, the workshop produced orders from Napoleon III and couture houses like Worth. In 1948, François opened a studio on Sunset Boulevard and created embroideries for film-studio couturiers in Hollywood until his father’s death a year later brought him back to France where under his leadership the maison became the preferred embroiderer from Pierre Balmain and Cristobal Balenciaga to Christian Dior and Hubert de Givenchy.

Like Elsa Schiaparelli, Yves Saint Laurent worked only with him since they met in 1963, with a collaboration lasting 44 years and producing famous pieces like the Van Gogh Irises and Sunflowers of the summer 1988 collection, each requiring 600 hours of work. Coco Chanel never worked with Lesage because Schiaparelli was a rival, but after she died and Karl Lagerfeld took over in 1983, François started collaborating with the German designer, producing many memorable pieces like the one inspired by Coco’s coromandel screens. His vast archives were an endless source of inspiration but when a Vionnet sample was coveted by Azzedine Alaïa, John Galliano for Dior, and Lagerfeld for Chanel, he refused each time and firmly told them “This is Vionnet.”

The maison’s collab with Vionnet was a very important one—to accommodate the delicate fabrics like chiffon which the designer favored for her signature bias-cut dresses, Lesage had to create designs that did not weigh down the fabric and adopt a technique known as Tambour where a tambour hook is used for bead embroidery, catching the thread on the backside of the fabric and pulling it to the front side to attach beads and sequins.

Lesage’s professionalism and dedication were something all the top couturiers appreciated. Whichever theme they decided on, he would respond with up to 30 designs, of which the designer chooses but a few. Each design is stored in the archives which have accumulated over 70,000 samples, representing over nine million hours of hard work. It was a vocation of which he said, “I never forget. I am only an embroiderer and my imagination should be framed in simple materials—silk, sequins, stones. But they give birth to a firebird dream that I just want to catch on the tail. But the dream can’t be caught—it’s always in front, making our life more beautiful.”