Vivienne Westwood’s fashion for a better world

The fashion of Vivienne Westwood, who passed away last December, has had such an influence on designers and style enthusiasts since the ’70s that many looks and images seen today can be credited to her.

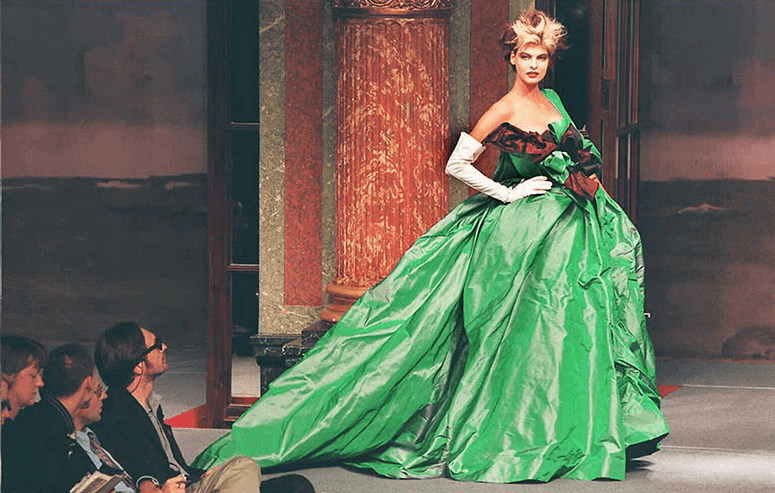

For our own collection at the recent Ternocon, her 17th- and 18th-century reinterpretation of corsets and panniers, underwear as outerwear, Josephine empire gowns and mini crinis—which also inspired Christian Lacroix’s puffball skirts and the bouffant silhouettes of the ’80s—were all incorporated in new versions of the balintawak and terno.

Her iconoclastic style used clothes as a form of her own brand of patriotism, expressing or rebelling against the social and political status quo and shaping group identity. Believing that “orthodoxy is the grave of intelligence,” she used what she called her “built-in perversity” to shape the look of punk by subverting rock iconography, royalty, art, and religion while focusing on the English tradition of tailoring.

Surface decorator and restorer Tats Manahan was able to meet Westwood in 1977 at the London’s King’s Road shop, which attracted her while meandering in the area. Greeting her were the partners Westwood and Malcolm McLaren, who started the boutique in 1974 when it had its first and most notorious identity: “SEX,” proffering fetish wear for those with underground tastes and young proto-punks. It was later renamed “Seditionaries: Clothes for Heroes” in 1976, when there were still risqué pieces like bondage trousers with bum flaps and hobble straps but there were also more accessible pieces like jeans with studs, which Tats took a liking to but had to “torture” herself struggling into because of their impossibly tight design. The only way to get into them was lying down on a bench, which was provided in the fitting room.

Tats found Westwood pleasant and friendly enough “but with an underlying edge.” “I must have been a curiosity,” she recalled, “this Asian totay who just wandered into punk territory.” But Westwood, with her long red hair in rock ’n’ roll disarray, must have found a kindred spirit in the Pinay, who sported a frizzy hairdo. She even introduced Tats to her nephew, Timothy Westwood, who was gracious enough to take her on a picnic at one of the city’s sprawling parks.

The pieces at Seditionaries had highly charged imagery like swastikas and the Queen with a safety pin through her lips; naked breasts and pornographic cowboys printed on frayed T-shirts and muslin tops. Westwood’s signature of clothing yet unclothing the body had its beginnings here with “nippled” shirts using bunched fabric, typical of the wardrobe of The Sex Pistols, the punk rock band managed by McLaren. Festooned in razor blades and chains, the group delivered aggressive songs like Anarchy in the UK, reflecting the nihilism of the country in the ’70s.

The runway has always been her political platform, with models carrying placards demanding fair legal trials for Guantanamo Bay prisoners in 2008.

Born Vivienne Isabel Swire in 1941 to Gordon and Dora (Ball) Swire, both blue-collar factory workers, the designer actually had “an incredibly happy childhood in the rolling hills of Derbyshire, the most beautiful place in the world,” as she told her brother, Gordon Swire, in a video interview. Moving with the family to London in 1957, Vivienne, who already had sewing classes at age eight, attended the Harrow School of Art and later took a job as a teacher in a primary school where she was already unconventional, taking her eight-year-old students to watch Battleship Potemkin, the 1925 Eisenstein film about proletariat revolution.

She married Ben Westwood, a toolmaker, in 1962, but left him just a few months after giving birth to their son, Ben, and divorced him in 1965 when she met McLaren, a friend of her brother. Their son, Joseph Corré, was born in 1967. Their romantic relationship ended in 1981, although they remained business partners, presenting the New-Romantic inspired Pirate Collection of frill-sleeved blouses and stiff felt hats before parting ways in 1984 when the shop became Westwood’s own.

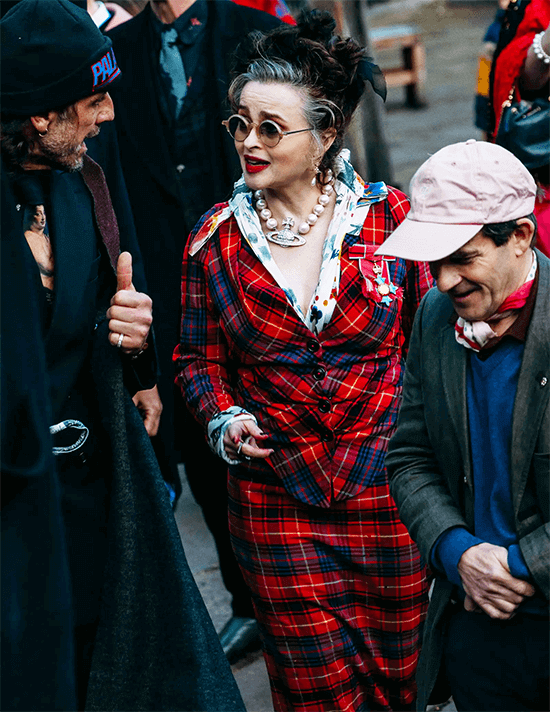

She would create some landmark collections that changed the way people looked, marked by the mini-crini combining the Victorian crinoline with the miniskirt in 1985 and her diffusion line Anglomania in 1993 with tartan derriere padding.

“I was messianic about punk, seeing if one could put a spoke in the system in some way,” she said. “I realized there was no subversion without ideas. It’s not enough to want to destroy everything.”

She was credited for reviving the British fashion scene in the ’80s, and named one of the six most influential designers of the 20th century by WWD publisher John Fairchild. She met Austrian fashion student Andreas Kronthaler in the late ’80s, married him in 1992, and partnered with him on the Westwood label.

Her name would be linked to some memorable moments in fashion, like Naomi Campbell tumbling down the runway from sky-high purple python platforms in 1993 and famously receiving her OBE from the Queen in 1992 sans underwear, remarking, “I wished to show my outfit by twirling my skirt but as the photographers were practically on their knees, the result would be more glamorous than I expected.”

She became a dame in 2006 when her designs would be worn by clients as diverse as Camilla, who is now Queen Consort, and pop star Miley Cyrus, who got married in a Westwood gown.

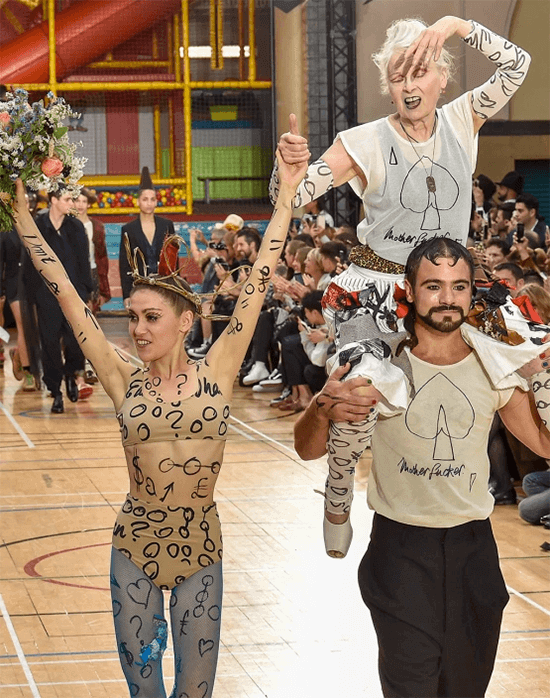

The runway has always been her political platform, with models carrying placards demanding fair legal trials for Guantanamo Bay prisoners in 2008. For climate change, a 2013 show had a banner calling for a revolution and in 2014 she shaved her head. At other times she would show support for US whistleblower Chelsea Manning and Wikileaks founder Julian Assange, as well as environmental charities like Cool Earth and Greenpeace.

She had always been independent, she told Time in 2009: “I own my own company so I don’t have businessmen telling me what to do or getting worried if something doesn’t sell. I’ve always had my own access to the public, because I started making clothes for a little shop and so I’ve always had people buying them. I could always sell a few, and somehow my business grew because people happened to like it.”

At the recent memorial in London, fellow designers, friends and fans came in full force wearing their favorite Westwood pieces—a virtual retrospective of her oeuvre. Helena Bonham Carter, who gave a eulogy, owns no fewer than seven of the cocotte dresses alone and admitted, “I have an obscene amount of her clothes. She’s a genius. She gives us instant body engineering with no lipo or diet… a true feminist and lover of women who understood the power of protest and empowerment. While Karl Lagerfeld tried to marry his cat, she drove a tank onto the prime minister’s front lawn as part of an anti-fracking protest.”

But the most moving statement came from Westwood’s life partner till the end, Kronthaler, who also summed up the revered designer’s life that would guide him and the company forward: “What she really wanted more than anything was to make the world a better place.”