Juan Luna to son Andres: ‘I will never leave you again’

Against the background of one of Paris and Manila's most notorious crimes of passion, filmmaker Martin Arnaldo looks into a poignant letter Juan Luna wrote to his son Andres.

Feb. 7, 1893. The Southern courtroom of the Palais de Justice. Seated beneath the Christ of Bonnat, Pillet-Desjardins, the president of the Cours d’Assises de la Seine, addressed Juan Luna de San Pedro: “In 1892, you endured a great tragedy and with the imagination particular to your race, you saw the commencement of a curse that was weighing on you. I am referring to the death of your daughter (Maria de la Paz, or ‘Bibi’), closely followed by that of your father.” Luna trembled in his bench and literally began to sob.

Some newspapers speculated that it was these tragedies that most probably drove Luna and his wife, Paz Pardo de Tavera, apart. Félix Décori, the lawyer of the prosecution, alluded to this separation while reading aloud one of Paz’s letters, dated July 11, 1892: “I don’t know the things that are going on in my head, and since I can’t communicate my ideas to Luna who, as you know, has a very strange character, nor to Mom so as not to hurt her, I have to struggle on my own.”

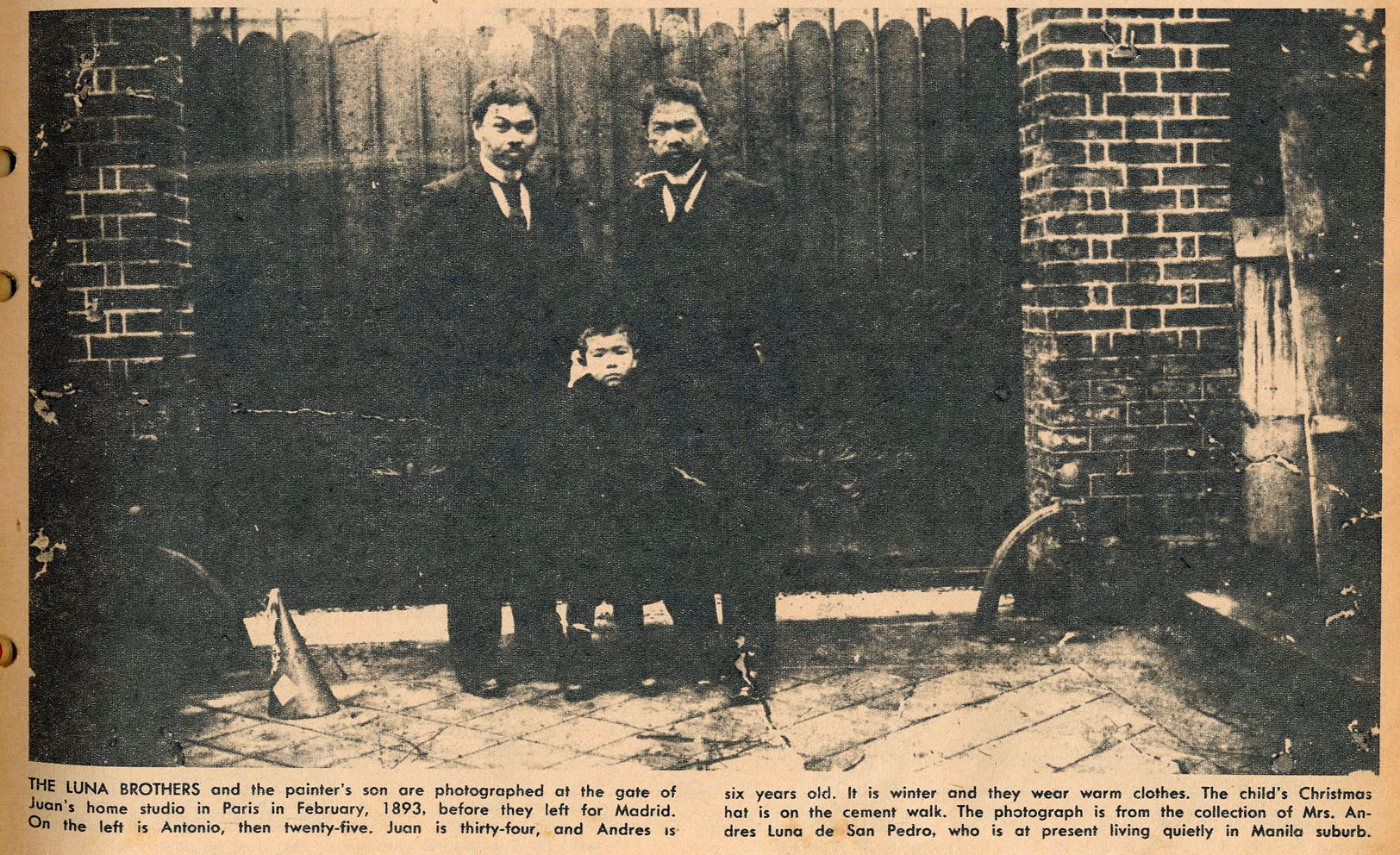

(From left) Antonio Luna, Andres and Juan Luna in Paris

This letter was written just before the doctors prescribed Paz a visit to the thermal waters of Mont-Dore for her asthma. It was said in court that after Bibi’s death, Luna had a difficult time accepting any physical separation from anyone he loved. So it was reluctantly that he saw her off in the early days of August, with their five-year-old son, Andres, and his English nanny. Luna couldn’t go with them because he was working on an important commission in Paris, but Paz promised to write to him every day.

Luna wrote practically every day. His letters resonated with love, passion, and grief for their lost two-year-old, Bibi. This grief also manifested itself in concern about Andres. Luna worried about the tiniest things: that he not catch a cold, for example. After the death of Bibi, Andres became everything for Luna. While waiting for his return, Luna created a small alleyway for him in their garden in Paris and planted a tiny cherry tree that Andres would be able to reach with his tiny hands.

The days went by, and Paz’s letters grew fewer and further between. There were rumors that her familiarities with a certain Monsieur Dussaq were creating quite a scandal at Mont-Dore. Luna decided to immediately call her back to Paris. According to Mademoiselle Gorricho, one of the household maids who testified in court, when Mme. Luna came back, she no longer called Luna by the tender “Loulou.” Luna also noticed that Paz had replaced her mourning clothes with bright dresses, and she spent entire afternoons on solitary promenades.

Sensing that his wife was seeing someone, Luna started following her. On Sept. 10, he was led to the 25 rue du Mont-Thabor, where his suspicions were confirmed. Luna became enraged. He forced a confession out of her at gunpoint, he burned her dresses, and he violently beat her on several occasions. It was too much for Paz’s mother, Doña Juliana, who feared for her daughter’s life. She asked her son, Trinidad, to intervene and separate them.

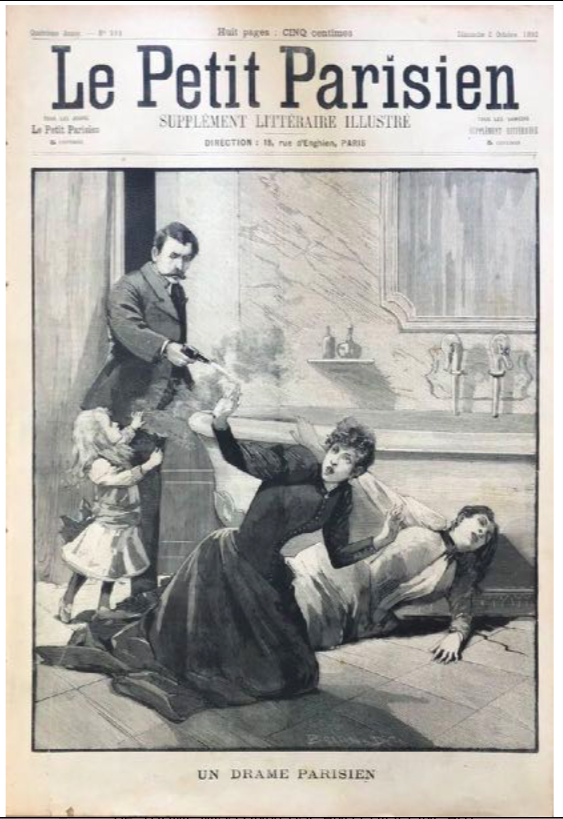

On the fateful morning of Sept. 22, 1892, on Trinidad’s advice, Paz and her mother locked themselves up with Andres in the third-floor bathroom. Luna knocked at the door, looking for Andres, but Doña Juliana refused to open it. This infuriated Luna, and he threatened to get his gun. The women screamed for their lives through the bathroom window, alerting the entire neighborhood.

A few months later, when being tried for the gruesome murders of Paz and Doña Juliana, Luna called this scene a “guet-apens”: a trap to publicly shame him in order to make a divorce possible, which would separate him from the only child he had left. Furthermore, not only had he lost his daughter, he had lost his father as well, and Paz’s affair made him feel that he had lost her, too. He couldn’t afford to lose Andres.

In a gross miscarriage of justice, the jury acquitted Luna on all counts. Luna was greeted with an ovation as he exited the Conciergerie. He climbed into a carriage to fetch Andres, and they dined in a nearby café with Luna’s brother Antonio and a few friends. “Will you return to the countryside, Papa?” asked Andres. “No, I will never leave you again,” answered Luna, holding him in his arms.

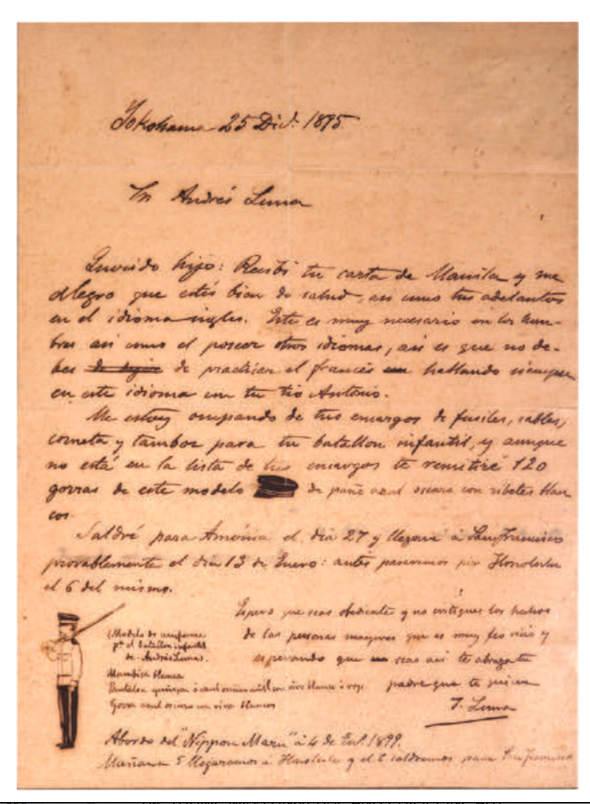

Yokohoma, Dec. 25, 1898. Luna began writing a letter to Andres, who was hundreds of miles away in Manila. It was Christmas Day, but Luna didn’t even mention it. Instead, he drew him a uniform for his collection of toy soldiers. Luna finished his letter on Jan. 4, 1899, on board the Nippon Maru, which was approaching the coast of Hawaii en route to the United States. One can imagine how his promise may have echoed loudly within him. (All rights reserved. Copyright © 2020 by Martin Arnaldo.)

This charming yet heartbreaking letter was written with Juan Luna’s acquittal for the murder of his wife looming in the background. It and other poignant historical papers are highlights of the forthcoming León Gallery Kingly Treasures Auction on Nov. 28, 2020.