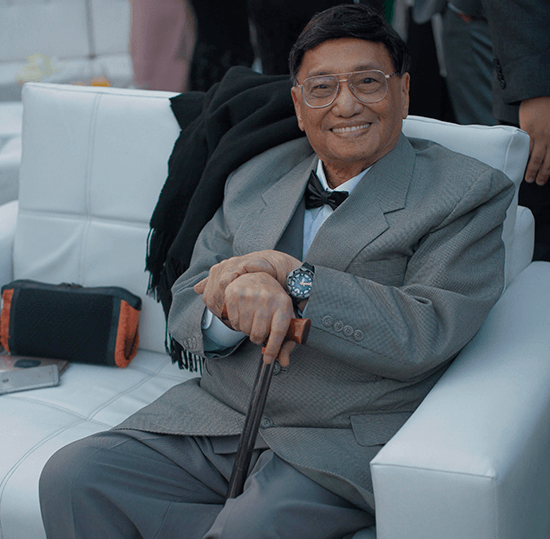

To Laki with love

To me, he was Laki.

“Laki” being Pangasinense for grandfather, or “lolo.” All these things about Laki’s accomplishments I learned later in life, but knowing the man you wouldn’t think he was capable of such things. Larry Henares was always so inappropriate. One time I brought my friend, a former sexy actress to his house to borrow suspenders, and he asked her what she did. “I’m an actress,” she said. “You’re not one of those actresses who likes to show her tits, are you?” She was dumbfounded, and I silently told her “he doesn’t know” as I slowly ushered her out. Another time he was talking to my American friends, telling them that he’d been to “all 50 states! I’m more American than you!” He then proceeded to tell them how much he hated Republicans because they were fascists. I’m pretty sure half of them were Republican.

To piss him off, I’d tell him that I was thinking of becoming a priest. The first time I did it, he banged the table and dropped his utensils. “You can’t be a priest! You’re a Henares, you’re malibog!” He’d regale the lunch table with stories of my lolo on my mother’s side and how they’d all call him “kabayo” because he was well-endowed. One time he asked my college girlfriend about the size of my you-know-what, and she came running to me completely red in the face. When a friend had a sex video scandal, Laki showed up to lunch with a pirated DVD of the sex video and asked my friend to sign it. I was literally rolling on the floor as Laki started asking him things like, “How does she do that? I’ve never seen such things! What a whirling dervish!”

Whirling dervish. The man spoke like a character from 1940s comic strips. He’d say things like “Jiminy Krautz” or “by gum,” and half the time I didn’t know if he was making it up. He would memorize passages from Shakespearean plays or William Wadsworth Longfellow, just casually dropping them in his booming voice during conversations. He’d tell us stories of the war, of raising a crazy household of six children, of the love of his life: his wife Cecilia, our Bae. When you would visit Laki, it would always be a show. And he didn’t even have to be talking to you. He’d be typing his latest article with two fingers (and to think after around eight books you’d have learned to properly type by now), just laughing out loud or reacting to what he’d been writing, as if he wasn’t the one writing it. Even when he’d go to the bathroom you’d hear him exclaim, “ay t*ng ina, ang ganda!” when he’d have a good bowel movement.

Larry Henares taught me how to write. He taught me how to enjoy the humanities — art, literature, cinema. Most importantly, he taught me how to live.

And he always had time for his grandchildren, all of whom he loved dearly, even if he would often forget our names and just call us “Henares.” For elocution contest in grade school he would tirelessly rehearse with me, and while my classmates would recite pieces entitled “Busy Buzzy Bee” or “All Things Bright and Beautiful” he would have me declaim the most violent passages from Shakespeare: Blood and destruction shall be so in use, and dreadful objects so familiar, that mothers shall but smile when they behold their infants quarter’d with the hands of war. When I got into comics he’d get into comics with me, and my first ever article co-written with Laki, came out for Metro magazine. I was 11 years old. We would watch movies like Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria and Ernst Lubitch’s Ninotchka, and even while we weren’t he would describe movies like Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times with so much detail and fervor that it felt like you were watching them.

As I type this, I realize that Laki might have been the most influential figure in my life. He taught me how to write. He taught me how to speak in public. He taught me how to enjoy the humanities—art, literature, cinema. Most importantly, he taught me how to live. Up until his last moment he always looked at the world through rose-colored glasses. There was always something to laugh about, to gleefully enjoy, to be inappropriate about.

Usually, when one writes tributes like this, they end with some profound quote about death. Funnily enough, mine comes from none other than Laki himself, from his essay “To Cecilia with Love,” written after the passing of Bae:

If one did not believe that there is a just and merciful God, and that immortal souls will meet again after death, life on Earth would be intolerable. It would have no purpose, no everlasting love, no ultimate justice. Life would not be worth living. But we do believe, and hope and pray that someday in God’s own time, we will be reunited with our beloved ones’ departed. It is this hope of reunion for all eternity that sustains us in this hour of loss and bereavement.

“I like you, grandson,” he told me once, in one of those normal days where I’d watch TV as he’d type away on his computer. “I love you. That is my obligation. But I don’t need to like you. And yet, I do.”

I like you too, Laki. And I love you so much. ’Til we meet again.