The women who shaped the Commission on Human Rights

Through the years, the Commission on Human Rights has been hailed for its efforts in looking into human rights violations that are taking place in marginalized and vulnerable areas of the country.

Since its establishment in May 1987 under the Philippine Constitution, there are inspiring women who have significantly helped shape the landscape of human rights in the country.

In all of my 33 years working at the Commission, I served under seven chairpersons, five of whom are women. Although all of them did not serve their entire seven-year tenure, they contributed to the growth of the national human rights institution. Characteristically brave and bold, they faced their tormentors and the odds stacked against them, serving as an inspiration for others to go above and beyond for the protection and promotion of human rights.

Mary Concepcion Bautista

Even before becoming the first CHR chairperson, Mary Con—as she is fondly called—had human rights in her heart. She was a feisty lawyer and a women’s rights advocate who rose to prominence when she successfully put to prison the four rapists of actress Maggie dela Riva. She was also known for her crusades for consumer rights as she fought against multinational corporations to protect consumers from dangerous products. To protect poor litigants, she worked for the creation of a free legal aide program. As an active member of the progressive Concerned Women of the Philippines, she campaigned for the rights of political detainees. She was among the few female legal luminaries who raised their voices against the abuses of the government.

After the EDSA Revolution, late former president Corazon Aquino appointed her as a commissioner of the Commission on Good Government. With the creation of CHR, she was appointed as chairperson and served until her untimely death in September 1992.

Her tenure was marked with many firsts such as the first human rights training for the military and the first Philippine country reports to the United Nations Treaty Monitoring Bodies. The report on the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights was jointly prepared by the CHR and the Department of Foreign Affairs while the Report on the Covenant on the Eradication of Racial Discrimination was separately prepared by the CHR as insisted by Mary Con herself. Under her leadership, the CHR established its Visitorial Services to implement its constitutional mandate to exercise visitorial powers over all detention facilities. Through this service, CHR was able to secure the release of countless illegally detained persons or persons deprived of their liberties. The Financial Assistance Program for victims of human rights violations was also established to ease the economic burden of complainants in pursuing their cases.

As the CHR navigated the birth pangs of a newly organized and unique institution, Mary Con showed grit and determination to face the challenges of her adversaries as she tested the extent of the powers of the Commission over issues of economic, social, and cultural rights. The greatest legacy of Chairperson Bautista is her defending the independence of the CHR from the powerful Commission on Appointments. When then Senate president Jovito Salonga asked Bautista to submit her appointment papers, she refused to subject herself in the confirmation process of the CA. Instead, she elevated her case to the highest tribunal where she argued her position against Senator Salonga and the Commission on Appointments Committee on Social Justice, Human Rights, and Judicial Bar. The Supreme Court ruled in her favor that the chair and members of the Commission who are appointed by the President (Cory Aquino) do not need confirmation by the Commission on Appointments, which set the precedent for the succeeding members. In affirming the independence of the Commission, the SC likewise ruled that the tenure of the Chair and members of the HR Commission is not at the pleasure of the president. They could be removed from office only for cause.

Aurora Navarette-Recina

A retired Regional Trial Court judge, Chairperson Recina was appointed in the 1990s, taking over the helm from her predecessor, Chairperson Sedfrey Ordonez who served the remaining term of Bautista. A soft-spoken lady who looked frail and unassuming, she was actually firm in her decisions and actions. Under her leadership, the Commission implemented a reorganization that upgraded the 12 field units into regional offices and the central support services into departments without going through of the Department of Budget and Management. Having been admitted as a member of the Constitutional and Fiscal Autonomy Group, the CHR invoked fiscal autonomy and asserted its power to create new offices specifically the regional offices to have wider reach—the poor people in the grassroots. Unfortunately, the upgrading of the salaries with the use of savings was questioned by the employee association, which filed a case to stop its implementation. The case dragged on until the SC decided in favor of the employees in 2014 long after Recina’s time. In its ruling, the SC clarified that the CHR, created by the 1987 Constitution, has limited fiscal autonomy and that such upgrading requires the approval of the DBM. This was a big blow to the independence of the Commission which has been working within a limited budget and a lean organizational structure of only 800 personnel at that time. While the upgrading of salaries stopped, the Commission did not waver and continued to service the regions as full-fledged offices it created with limited budget. The Commission has since took the bitter pill of being subjected to the approval of DBM for its requests for additional funds for expansion and upgrading.

It must be emphasized, however, that elevating the field units as regional offices was necessary and is a significant initiative to enable the CHR to have a stronger position, not mere presence, in the regions. The CHR regional offices have been recognized and able to participate in regional inter-agency bodies and present the CHR positions in all human-rights related issues at the same level as their regional counterparts.

During Recina’s administration, the Commission embarked on a grassroots human rights program, called the Barangay Human Rights Action Officer. With her leadership in the Soroptimists International, the Commission partnered with this women’s group to reach out to as many barangays as possible to establish Human Rights Action Centers manned by the BHRAOs. The Centers could receive complaints of human rights violations which would be referred to the Regional Offices. The BHRAOs also serve to provide basic human rights information and operate a referral system for other human rights services.

When she stepped down as chair in July 2002, the seven-year term of office of the chair and commissioners was reiterated and finally put to clarity. The chair and commissioners are appointed every seven years since 1987. The term starts from May 5 of the appointing year and ends on May 4 on the seventh year. Thus, when her successor was appointed, the appointment paper stipulated that as Chair, Purificacion Quisumbing would serve only the remaining years of the seven year term, which was to end on May 4, 2008.

Purificacion Valera-Quisimbing

Before becoming the chair, Prof. Puri Quisumbing, as she was known internationally was appointed as Commissioner of the Third Commission. She was the representative of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and served as a Director at the Center for Human Rights in New York from 1995 to 1997.

Steeped in international human rights laws, Puring, to local friends, widened the international perspective of the CHR and introduced institutional reforms to respond and adapt to the dynamic changes in human rights amidst global developments. Under her leadership, the CHR embarked on an organization-wide reform program to strengthen its capacity to respond to its mandate as an independent national human rights institution. The Commission went into a re-engineering mode in three ways: defining its clients and stakeholders and then re-defining its roles vis-a-vis the stakeholders—human rights victims, the government, and the civil society; reorganization of its structure to respond to specific clients such as women, children, indigenous peoples, persons deprived of liberties, and other vulnerable sectors, as well as to the evolving human rights issues such as the right to development; and refining its work systems and processes to improve its programs and services. These reforms provided the template for the next succeeding institutional developments within the CHR.

Chair Quisumbing introduced the concept of the CHR as Ombud for women and children and created the Women’s Human Rights Center separate from the Child Rights Center. Aside from the institutional overhaul, the Commission pioneered in the adoption of the Rights-Based Approach to governance and development. The CHR, through the RBA program, has been a catalyst in mainstreaming human rights in development planning and ensuring that development and government activities across the board are informed on human rights principles.

Under her leadership, CHR forayed into the dual but anti-thetical roles of a national human rights institution: as critique or watchdog and as adviser and assister. She championed the role of the CHR as monitor of the government in complying with its human rights treaty obligations.

With Quisumbing’s UN exposure and international network, CHR was able to secure a medium term-funding assistance for its advocacy and institutional development programs. This first big-budget project was the European Commission-assisted project, “Enhancing the Role of National Human Rights Institutions for the Development of an Asean Human Rights Mechanism.” Through this, the Commission facilitated the institutionalization of the ASEAN NHRI Forum, a sub-regional body consisting of the national human rights institutions of five countries, namely, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Timor Leste.

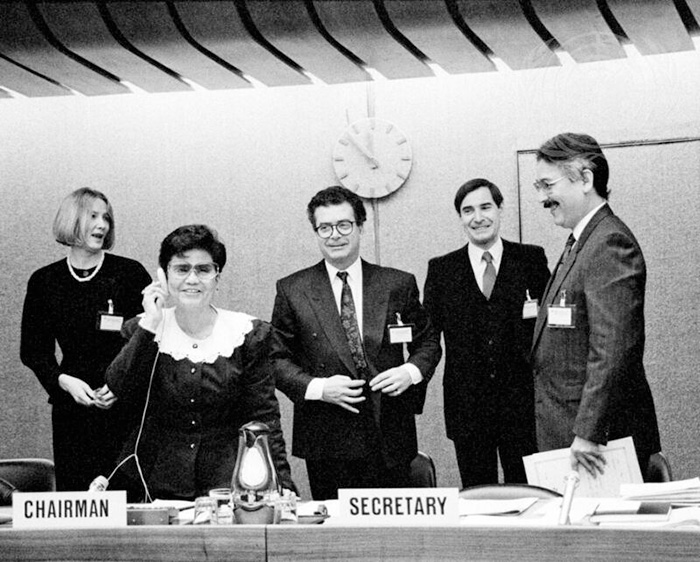

After her stint at the CHR, she was appointed as chairperson of the Human Rights Committee Advisory Council of the United Nations Organization and represented the Philippine State as a human rights expert. She was also elected Chairperson of the 46th Session of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, Geneva, Switzerland in 1990.

Leila Norma de Lima

Former Senator Leila de Lima earned the ire of her political enemies when as the chairperson of the Commission on Human Rights from May 2008 to 2010, she investigated the spate of extrajudicial killings in Davao City by the so-called Davao Death Squad. De Lima braved the dangerous investigation process that brought her to the “killing fields” and faced threats and warnings amid the uncooperative instance of the local government. The Commission later on came up with a report implicating then Davao mayor Rodrigo Duterte as the mastermind of the unsolved killings in the city. The congressional hearings on Duterte's drug war last year confirmed the findings of the CHR.

When she was appointed to head the CHR, de Lima humbly admitted to not being a human rights expert, but she learned very fast. With her strong grasp of human rights concepts and principles, international laws, and the work of a national human rights institution, she steered the CHR through challenging investigations, such as the Maguindanao Massacre, and new territories, such as elections.

Under her helm, the Commission was able to initiate electoral reforms to eliminate disenfranchisement of vulnerable groups such PWDs, detainees, senior citizens, and Indigenous Peoples. The staff admired her for writing her own speeches and reviewing papers and documents thoroughly with the eye of an eagle.

Elected as senator in 2016, de Lima chaired the Committee on Human Rights and Justice, where she called out Duterte’s war on drugs that claimed the lives of thousands of innocent victims. She authored several bills, four of which were passed into law: the Magna Carta of the Poor, the 4Ps Act or the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program, the Community-Based Monitoring Act, and the National Commission of Senior Citizens Act. She also sponsored or co-authored more than a hundred bills, some 23 of which have been passed into law.

Unfortunately, when she was accused of receiving drug bribes, some made a mockery of her personal life by using a fake sex video to tear her down. What is most appalling to us, CHR people who knew her personally, was the way her colleagues including the women in Senate turn a blind eye to her vilification at the hands of misogynists, and ultimately, ousted her as chair of the Senate committee on justice and human rights. During her six-year incarceration, she did not stop to call the attention of the government to the raging issues on corruption, injustice, human rights abuse, poverty. Inside the bare, damp cell, she wrote her reflections and statements in free hand.

As the first nominee of the party list Mamayang Liberal, Manay Leila hopes to continue her legislative work to provide those in the “laylayan” more access to basic services and protection from abuse.

Loretta Ann Rosales

When de Lima resigned as chairperson of CHR in 2010 to become the Justice Secretary, then President Noynoy Aquino appointed Loretta Ann “Etta” Rosales as her successor. She is perhaps the only living poster girl for victims of martial law. She was tortured and harassed, and suffered indignities as a woman when she was incarcerated during the martial law regime. As the founder of the Alliance of Concerned Teachers (ACT), she was branded a communist and a threat to the country.

A woman of steely guts, Etta eventually became a member of the House of Representatives as the first nominee of the AKBAYAN. There, she authored and co-authored human rights laws such as the Human Rights Victims Compensation Law, the Abolition of the Death Penalty, Anti-Torture Law, Declaration of National Human Rights Week Celebration, among others.

Under her watch, the CHR exposed and investigated the “Wheel of Torture,” a game to select the form of torture on detainees to extract information and to force them to confess. As a result of CHR’s investigation, six policemen of the Laguna Police were convicted and dismissed. Among the notable human rights violation cases investigated or resolved during her time were the complaints of abuses of the mining corporations, such as the Oceana Gold Mining in Didipio, Quirino and the violations of Indigenous People's rights.

One of the highlights of her tenure at CHR is the inclusion of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights as one of the thematic concerns of the agency. BHR requires is the conduct of a human rights impact assessment of development projects and industrial programs. The CHR facilitated the pilot of a human rights impact assessment tool used in the Tampakan Copper-Gold Mine Project in Southern Mindanao in 2012-2013.

Chair Etta also clinched a multi-year funding from the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation to strengthen the CHR as the national human rights institution of the country. The Fortaleza project eventually gave impetus for the expansion of its regional services and improvement of its facilities with the construction of its own office buildings.

Now turning 86 years old, Etta is truly a survivor and a living legend, a historical figure whose faithful narrative of the horrors of martial law cannot be disputed. With most of her comrades having gone to the great beyond, Etta is an inspiration to the young and old as she continues to keep the fires of human rights advocacy burning.