Bumping against the walls of heaven

This isn’t the definitive Anthony Bourdain documentary. How could it be?

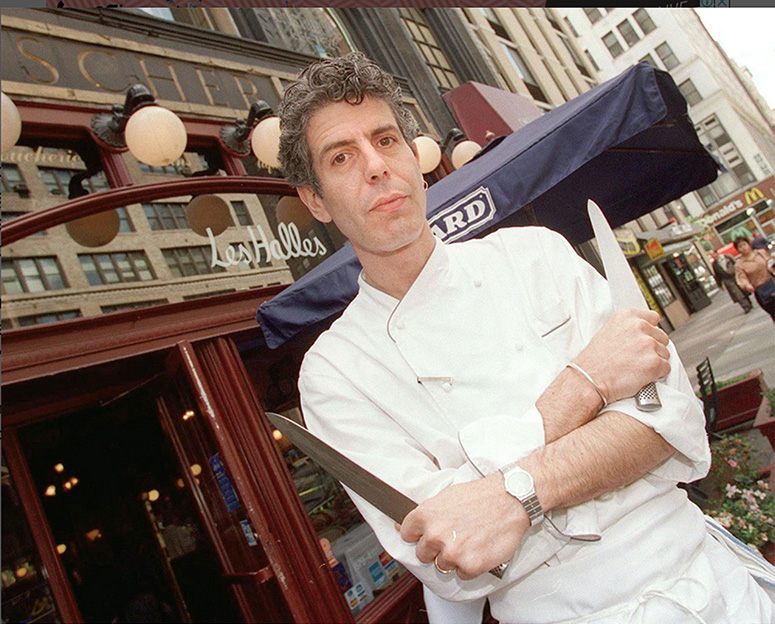

With a title like Roadrunner: A Film About Anthony Bourdain, Morgan Neville’s mix of behind-the-scenes footage and present-day interviews with friends, ex-wives, producers, musicians and painters could only be an impressionistic take on the iconic chef-turned-author-turned-celebrity’s life, not the final word. (Controversially, Neville even uses AI technology to conjure up Bourdain’s voice from “beyond” in a few segments.)

Who knows if Bourdain even liked the Jonathan Richman song that blasts over the opening titles? Who knows if he would have liked the ascending guitar coda of Television’s Marquee Moon as it plays over a montage of his rise to celebrity? It doesn’t matter. It’s the music we might like to hear playing over those moments. (For the record, chef and friend David Chang claims that Bourdain’s favorite song was Anenome by The Brian Jonestown Massacre.)

Roadrunner touches down on the many tangents of Bourdain’s life, the people left behind, like interviewees from Citizen Kane. Even they seem baffled by why the food guru took his own life in 2018.

“I don’t know,” shrugs friend/musician John Lurie when asked by the director. “That’s why I’m here.”

At the end, Tony felt alone and that he couldn’t talk to anybody about the pain that was going on inside him.

From teenage rebel to dishwasher in Manhattan to cook to chef to junkie to writer to global celebrity, “one thing led directly to the other,” he says in that instantly recognizable voiceover; Kitchen Confidential — the “obnoxious but wildly successful memoir I wrote” — became a calling card to adventure, fueled by his misadventures.

TV soon beckoned. From his initial shyness when A Cook’s Tour began shooting in 2000, suddenly “a switch flipped,” says one of his producers, and flights of fancy took off:

“This is bumping right up against the walls of heaven,” he rhapsodizes in Bangkok, chopsticks in hand, lifting a chunk of crab roe wrapped in noodles. “We’ve reached the mountaintop.”

Next stop: international food guru. Culinary rock star. Icon.

He does seem to have 'shifted addictions,': from opioids to fitness, travel to romance, family to the open road, celebrity to solitude. Perhaps he feared that he’d lucked into this life, and wasn’t sure he deserved it.

Was it enough? Bourdain got married, had a daughter whom he doted on. Tried to lead a “normal” life. Something kept pulling from the other direction, though: the road.

He does seem to have “shifted addictions,” as Chang puts it: from opioids to fitness, travel to romance, family to the open road, celebrity to solitude. Perhaps he feared that he’d lucked into this life, and wasn’t sure he deserved it.

Or perhaps Bourdain’s life was simply a mad, desperate race to find something to believe in — whether it was food, or culture, or love, or family, or legacy, or people all over the world who had their own problems — and maybe a well-paid TV host who ate food with them wasn’t the answer to their problems, but Bourdain might believe, for a while, that his unique platform could mean something for them, too.

We don’t get a final answer to the director’s question. But there are hints. His relationship with Asia Argento fizzled out, and he seemed unmoored in France, shooting a segment with chef Éric Ripert. Within the next few days, he hung himself. Why? The abyss, finally, refuses to answer back.

The movie ends with emotional breakdowns from each filmed subject; it still feels raw. His longtime director Michael Steed believes that, “at the end, Tony felt alone and that he couldn’t talk to anybody about the pain that was going on inside him.” (The next shot flashes a Suicide Hotline 1-800 number onscreen.)

The film nearly ends on a lonely shot of Bourdain, in voiceover, walking away from the camera along some frigid Provincetown beach. His painter friend, David Choe, rejects that image: “He would have ****in’ hated that.”

Instead, the assembled supply their own endings: Queens of the Stone Age guitarist Josh Homme cranks out some rebel rock; Choe defaces a smiling mural of Bourdain with spray paint. Instead of a meditative solo walk, we’re left with a drunken Irish wake.

But is this just one cliché substituted for another? The thing about an ending that replaces one desired coda with another is that it makes it seem like suicide is a problem for us to solve about the person. When, all along, it was really a problem that they tried, but couldn’t, solve for themselves.