Why #NeverForget: A necessary reflection

I woke up to the grey, drizzly Monday morning of Aug. 15 weighed down by migraine, the now shabby aftershocks of a long night’s bout with gout, and the memory of a story by Harper Magazine contributor, Mark Slouka – “Hitler’s Couch” – found in his book, Essays from the Nick of Time (Graywolf Press, 2010).

Slouka begins by relating his father’s nightmare, and later leaps to his own wide-eyed vision of the unspeakable as still an undergraduate of Columbia College. It was an image so disturbing to the young would-be author that it stood in his memory as a “featuring blow to my life”.

Slouka took a job as caretaker of the elderly and walked to 69th Street off Broadway, to an apartment of one old lady named Beatrix Turner. She was said to have been a former news correspondent through much of World War II.

[*Trigger warning: suicide]

No mention of the last legs of World War II would be complete without any reference to the Reich Chancellery in Berlin where the Nazi Führer, Adolf Hitler, spent his final moments prior to firing a gun on himself. Beatrix Turner claims she was one of few eyewitnesses to the defeat of what was perhaps Europe’s most bloodthirsty tyrant.

To prove her claim, Beatrix Turner gropes in her cabinet of souvenirs and showed Slouka a piece of cloth which not only wore the stitches and designs of the couch where Hitler allegedly breathed his last (as proven by a photograph Ms. Turner pointed out in Life magazine), it also bore the bloodstains stains which supposedly belonged to the Nazi leader.

“What I reacted to – instinctively, I suppose – was the terrible smallness of the thing, the almost vertiginous compaction of the symbol,” Slouka later wrote in 1998 for Harper’s (the essay later on appeared in Best American Essays 1999). “Behind the ridiculous cloth with its vaguely shit-brown stain, I could sense the nations of the dead pushing and jostling for space, for room, for a voice; it was as though all the sounds of the world had been drawn into the plink of a single drop falling from the lip of a loosened drain.”

Slouka “left the apartment soon afterward,” he later recalled. “At the bottom of the unlit, cluttered alley, rising like a canyon to the sky, I pushed open the heavy iron gate to 69th Street and started to run.”

In his Coda in page 20, he thereafter reflects on his experience of seeing the piece of cloth.

“History resists an ending as surely as nature abhors a vacuum; the narrative of our days is a run-on sentence, every full-stop a comma in embryo. But more: like thought, like water, history is fluid, unpredictable, dangerous. It leaps and surges and doubles back, cuts unpredictable channels, surfaces suddenly in places no one would expect […] Recognizing the limits of chronology, resisting its unforgiving dictates, is our duty and our right. There is no contradiction.”

Slouka’s story, I felt after reading it, posts a grim reminder, or better yet, a dour metaphor of our own encounter with aggression, that of Rodrigo Duterte’s “drug war”.

I placed the phrase within quotation marks for the simple reason that I, and perhaps many in my profession, have always thought of it as bogus, a counterfeit blitzkrieg, a sleight of hand aimed at fooling us into believing that the former regime had the public’s benefit in mind.

What it was, in fact, was a bloody war against the poor; worse, an assault against values enshrined in the Bill of Rights and our already fading grasp on justice, with others going on to speculate that it could even be a feud between some of the most powerful drug cartels in the country.

In hindsight, the drug war seems to be a dizzying promotion of violence as a tool to keep the public from being restless, even as one corruption case after the other reared its ugly head.

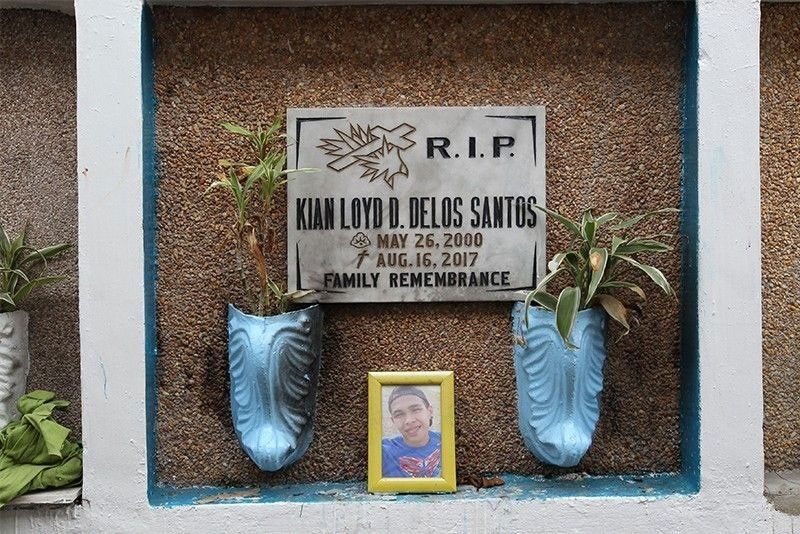

Well, whatever it was, the tens of thousands who were killed outside the little over 6,000 dead – close to 200 being children – the Philippine National Police had logged as the result of police raids is slowly proving to be the prologue of an upcoming sequel.

The murders were so open and flagrant, the impunity so widespread, that it’s almost impossible to think of the drug war as something totally remote from what is counted by many as crimes against humanity.

Senator Ronald "Bato" dela Rosa, former police chief and implementer of the drug war, is currently singing a different tune. Earlier this month, he stopped short of openly admitting that the former regime had triggered and enabled the murder of tens of thousands by favoring the pursuit of justice for drug war victims, that is, outside of the International Criminal Court.

Incumbent president Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr.’s plans to smarten up the drug war by treating drug dependency as a crisis needing humanitarian and medical attention doesn’t in any way, shape or form diminish its haunting brutality.

The thing with having a new administration is that more pressing problems are beginning to drown out older ones. Should Filipinos now set all this aside for the more indispensable issues hogging the headlines: the return of censorship, the red-tagging of authors and national artists, the attempts at historical distortion, or the more superfluous debates on sugar imports and Sen. Robinhood Padilla’s cable cars?

Like that swatch of cloth stained by tyrannical blood, a useless souvenir of days too traumatic to remember, should we leave history open-ended?

“To forget the dead would be akin to killing them a second time,” author Elie Wiesel said of holocaust deniers.

Not only that, but history leaping, surging and doubling back, and surfacing “suddenly in places no one would expect,” is never too far-fetched under conditions of inaction. How easy it would be now for the current administration to take the violent path left by Duterte, the continuing impunity serving as the doorway.

Previous administrations have built their idea of national unity, political reconciliation, and social peace on lip service, bereft of the scaffolds of justice. This was a grievous misstep for which we are now paying the price.

Think of how things are already escalating: just recently, two nuns from the Rural Missionaries of the Philippines have recently been charged with “financing terrorists,” or as reported, “for allegedly providing funds to the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and the New People's Army (NPA).”

The religious organization has long been the target of government harassment, with National Security Adviser Hermogenes Esperon even lodging a perjury complaint against the group early July 2019. The RMP was one of several petitioners against the Anti-Terrorism Law.

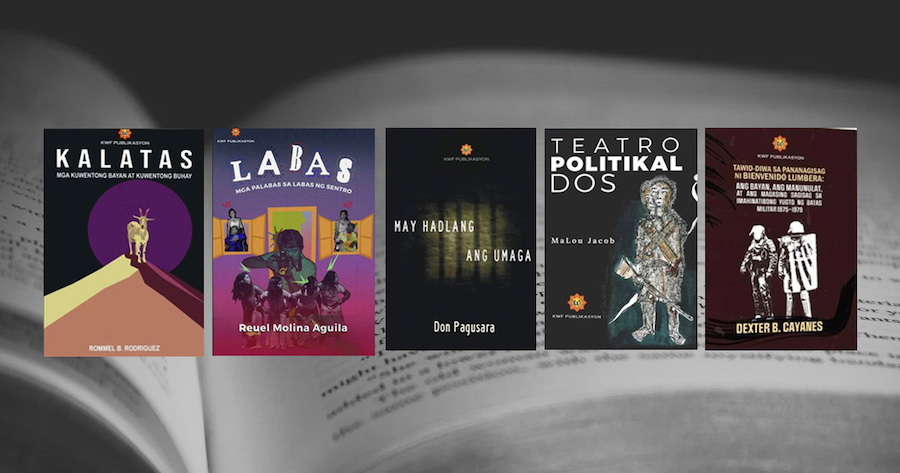

If RMP can be threatened, or the Komisyon ng Wikang Filipino forced to ban books the organization itself had chosen to publish, national artists and writers red-tagged, and two nuns charged for terrorism financing, what else are they poised to do?

Watching all this from a safe distance is never anything but a decision to side with oppressors.

What is, therefore, the enormous value offered by free expression if we will easily, and without any sense of guilt, give in to such threats? We can begin by making an open and clear stand, together drawing the line, or better yet, systematically reminding present and future generations that abuse of power will one day put everyone – including enablers – in harm’s way.

With a stubborn pandemic in tow, in a world turning darker by the minute, the odds are already stacked against them.

Our children deserve our courage.