Transcending homelands

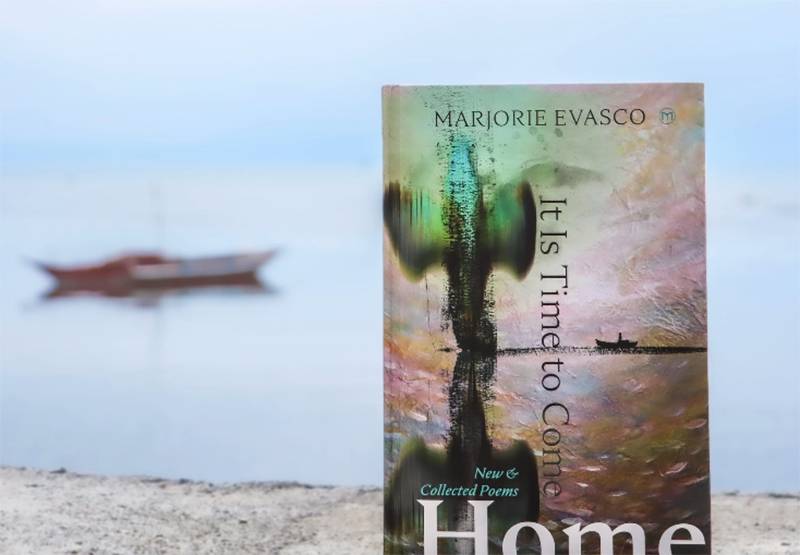

It must have established a record of sorts for a poetry collection, the recent series of “archipelagic” book launchings of Marjorie Evasco’s It Is Time to Come Home: New & Collected Poems, published by Milflores Publishing, Inc. Hardbound at 416 pages, the handsome volume was first presented in conversation with the public last Sept. 17 at the Manila International Bookfair.

On Sept. 21, another launch took place at Amarela Resort in Panglao, to coincide with the author’s 70th birthday celebration. On Oct. 6, the third launch was sponsored by co-publishers DLSU PH and Milflores in the Verdure, Henry Sy Sr. Hall of DLSU. Ten days later, another was sponsored by the Sunday Club Cebu and Cebu Women in Literary Arts Inc. at Casa Gorordo Museum. On Nov. 27, Holy Name University College of Arts and Sciences sponsored the launch at Balay Kabilin: Boholano Studies Center, in Tagbilaran City. And finally, on Dec. 1, 2023, the Ariniego Art Gallery in Dumaguete served as the venue for the launch/discussion/reading sponsored by the English and Literature Department, the Edilberto and Edith Tiempo Creative Writing Center, and the Silliman University Arts Council.

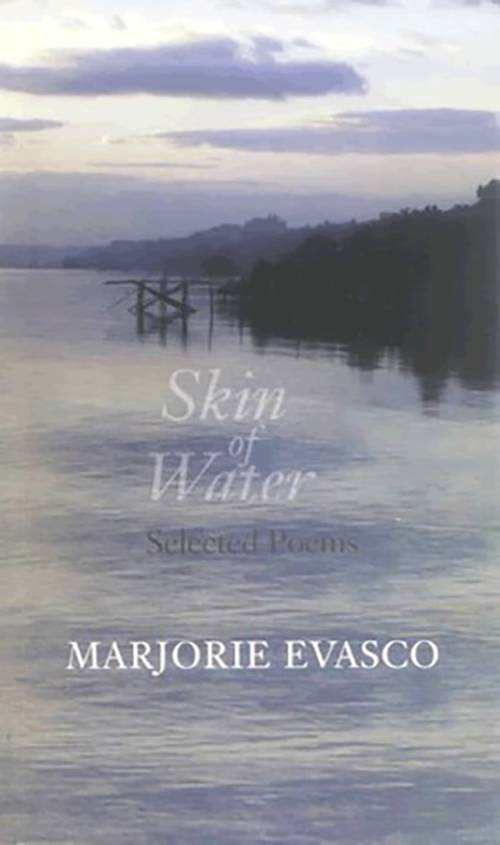

The esteemed poet deserved the love chain that now hooked up her fifth book in a span of five decades. Her previous collections (Dreamweavers: Selected Poems 1976-1986; Ochre Tones: Poems in English and Binisaya; Randi-Huni Ug Liban Pang Mga Balak; Skin of Water: Selected Poems; and Fishes of Light/Peces de Luz co-authored with Alex Fleites of Caracas, Venezuela, a Cuban citizen, poet and journalist) were now all out of print.

She decided “to take a longitudinal view of my work in poetry from the time I made the serious and conscious decision in May 1976 to learn and serve this difficult ‘craft and sullen art’ … as well as “to revisit my self-translation work from English to our mother tongue in my second collection … and revise these into Boholanon-Binisaya. … I hope this volume of new and selected poems will invite the attentive reader to follow the layered paths of my writing life from the time I crossed my home’s threshold in 1973 to go elsewhere, only to return again and again, in various magical and meandering ways, to the kiss of poetry in my forehead.”

The Professor Emeritus of Literature and University Fellow of DLSU-Manila has been involved in several languages: English, Filipino, Binisaya, and Spanish. An inveterate pilgrim, she also had to share her latest blessings in familiar haunts.

Fellow premier poet Merlie Alunan of Tagbilaran concludes in her Prologue: “The poet finds home at last, feet on land, in water, hands on stone, the heart turned to wind and light, as it is meant to be.”

The closing stanzas of the title poem manifest the kinship between favored sites and the images and narratives invoked.

“As the sun slips behind Maribojoc mountains, he comes/ to Bitoon, the deeper part of the river, stops for a chance/ to hear the bell thrown long ago by the people of Malabago/ to defy anger of shamans, priests, and greed of marauders./ No one owns the bell but the river.// … At the mouth of Abatan, children are hook-and-line fishing./ He calls to ask them if they were trying to catch Cogtong,/ giant fish guarding the bell. They laugh and tell him: No, but/ we’ve seen him flash huge red eyes, whip his very strong tail./ The old bell-keeper is alive and well.”

Of this latest thematic collection, I find most endearing “Tierra del Fuego,” whose last part, titled “5. Rites of Returning,” prepares the poet for closure even as she hails predecessors, whose names are familiar as those of dearly departed friends. The four stanzas of exultation through generations must be shared here:

“The moment you left Moto Sur,/ your closest comrade, away in Bhutan,/ dreamed a rustle of wings,/ stealth of white Roses./ Upon waking, Jose Victor told/ of your brief stop-over, your winged guide’s/ fiery eyes singeing each page he wrote on.// I sometimes hear you in the grove/ of my sleep, calling out the names of those/ who taught walkabout rhymes in synchrony/ with birds:// Franz! Estrella! Alejandrino!/ Angela! Edith! Edilberto!// Like you, we trust old hands of Tierra del fuego/ will welcome us at the beach-head of silence/ with libation of bag-ong dawat nga tuba.”

Imagery of home and other destinations, whether as pit stops or way stations, are recurring motifs in Evasco’s poetry. Select places, journeys, and fellow pilgrims distill the effervescence into the ripening wine of memories.

From her first collection, Dreamweavers of over four decades ago, “Ritual for Leaving” pictures the early ports of separation and lasting resonance.

“It is easier to leave/ in the middle of the day—/ The view from the port, postcard-pretty,/ Accented by kitchen smoke/ And blooming Acacia trees—/ An ordinary scene on an October day/ Which will probably be the same/ When you come back: a strange assurance/ Of infinities or that something/ We call indestructible.”

The title poem itself establishes core, groundwork, foundations of devotion, with its opening lines: “We are entitled to our own/ definitions of the worlds// we have in common.”

From Ochre Tones 12 years later, the friendships and allegiances grow, multiplying into extended families favored by the sky’s sacraments, as in the first stanza of the poem “Sylvia”:

“On your way to the sacred mountains/ You remembered me at a difficult pass,/ Seven years untrod except in memory./ Trudging up the bend of the road,/ A grown son ahead of you, forgetful/ Of your presence, stopped to recall/ How a child’s world must have looked:/ The mountains at ease, a wild Sun-/ Flower bursting like laughter, a treetrunk/ Growing Mushrooms after the rain.”

And from Skin of Water a decade later, with all the poems brought back, now side by side with translations into Spanish, her now iconic “Origami” offers another essence of transport:

“The world unfolds, gathers up wind/ To speed the crane’s flight/ North of my sun to you.// I am shaping this poem/ Out of paper, folding/ Distances between our seasons/ This poem is a crane/ When its wings unfold./ The paper will be pure and empty.”

Even in seeming immobility, at rest in isolation, the poet traverses locations by crafting physical, evanescent symbols as metaphors. Ultimately, it is the way Marjorie Evasco transcends homelands.