A dog’s world, after all

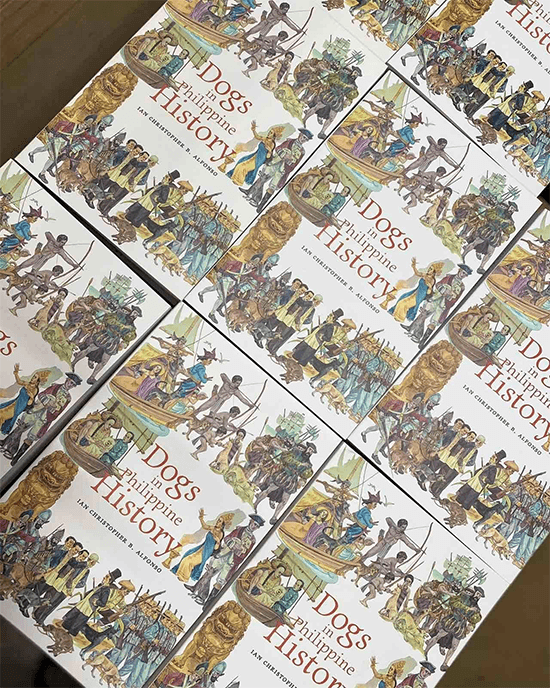

Launched on Aug. 5 at the NHCP Presidential Car Museum, Dogs in Philippine History by Ian Christopher B. Alfonso has quickly drawn interest for its unique topic.

Contrary to any presumption that it can’t but be a slim book, the author’s overarching passion for his subject has resulted in a weighty volume of over 700 pages.

The End Notes and Bibliography alone total 77 pages. Preceded by a Dedication, Acknowledgments, a couple of Prefaces, three Forewords, and a Prologue, the book’s 28 chapters that are also heavily complemented by visuals form a web of intriguing readability.

A senior researcher at the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP), Alfonso states at the outset: “This book chronicles the Filipinos’ cultural and historical encounters with dogs since the earliest documented existence of a domesticated dog in the Philippines about 4,000 years ago. It hopes to be of help in understanding Filipino culture and in fostering responsible ‘furrenthood.’ History attests to how our culture loves dogs.”

Cultural historian Felice Prudente Sta. Maria provided my copy as one of the Foreword writers. She disclosed: “The young historian did research over 10 years without funding. And people he didn’t know but whom he contacted helped with research. No bitching. No rivalry. Sheer appreciation for his effort.”

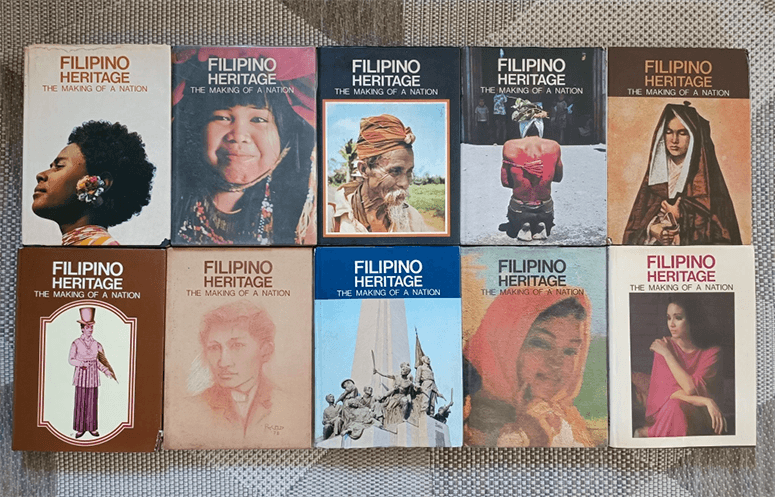

“A dogged effort it was,” chimed in Mol Fernando, who was also at the launch. The book is dedicated to his mother, Gilda Cordero Fernando, whose writings helped inspire the author. Alfonso fondly recalls her “The Philippine Aso: The Life and Hard Times of an Underdog,” anthologized in 1977 in Filipino Heritage: The Making of a Nation. “She exposed the sorry state of the Philippine Aso… She also tried reconstructing the origins of Philippine dogs and ennobled us to acknowledge our culture’s imperfections and appreciate the worth of our very own dogs.”

Ever humble and generous with his acknowledgment of sources, inspiration and intimations, Alfonso makes sure to credit all precedents and references he uncovered throughout his labors. Beyond published or written materials, these include anecdotes and a myriad of leads he encountered along the way, often by way of serendipity.

“It is a widely accepted theory that during the peopling of the Philippines, dogs were brought along by our seafaring ancestors called Austronesians as companions in hunting.” From there, as he explains, the chapters are “arranged in a convergent chronology.” From the Philippine aso to our aspins (asong Pinoy, our diverse if beloved mongrels), later known as askals (for asong kalye or street dog), the book spreads its net wide to assimilate sundry comparisons to foreign breeds.

In Chapter 7, “Melting Pot of Dogs,” a section leads off: “Our Ancestors Still Chose Aspin.”

“The earliest and most in-depth documentation about the Philippine native dog or Aspin is no less than Fr. Francisco Ignacio Alcina, SJ’s Historia de las Islas e Indios de Bisayas in 1668. A chapter in the book is dedicated solely to how the ancient Visayans regarded native dogs. In fact, Alcina noted how our ancestors looked down on the dogs brought to the Philippines by the Spaniards. They found European dogs useless, especially the small ones, most likely in hunting. The imported Spanish hunting dog mastinado (Spanish mastiff) was disliked by the Visayans because of its diet of three times an Ayam (Cebuano for dog) and proven pathetic in hunting…”

This book chronicles the Filipinos’ cultural and historical encounters with dogs since the earliest documented existence of a domesticated dog in the Philippines about 4,000 years ago. It hopes to be of help in understanding Filipino culture and in fostering responsible ‘furrenthood.’ History attests to how our culture loves dogs.

Another section billed as “Manila Dogs in America” details:

“The Galleon Trade, which lasted from 1565 to 1825, may have also introduced native Asian dogs to America, and from there to Europe. In 1808, scientist Alexander von Humboldt, in his famous work Ansichten der Natur (Aspects of Nature), recorded that Spanish colonies in the Americas had developed a fascination for a hairless Chinese dog called Perro Chinesco or simply Chino. (In 1836, the term entered the Cuban Spanish vocabulary as perro chino.)

It is actually the Chinese Crested Dog. Perro chino became popular in Cuba despite the existence of two hairless dog breeds in South America: the Peruvian Inca Orchid and Mexican Xoloi or Xoloitzcuintle, which Filipino kids familiar with the Disney Pixar animated film Coco (2017) would know as Dante. The belief was that the perro chino breed originated either from Manila or Canton (Guangzhou).”

Most fascinating are the middle chapters—Foo Dogs, Before Shih Tzus, Dark Age, Sigbin, Asong Gubat and Betsin. “Dark Age” covers the onset of rabies in the 18th century, from the West to local shores, when “mass killings … became the default option in Europe.” The same was true in the Philippines, as heartlessly ordered by the British occupiers of Manila from 1762 to 1764. But in 1863, Queen Isabella’s Royal Order on Rabies Prevention and Health Protocol took a more humane approach, allowing some Filipino gobernadorcillos to courageously take exception to orders from higher authorities.

Albularyo (healers) cures for rabies are also discussed. It wasn’t until 1885 that an anti-rabies vaccine was developed by Louis Pasteur, but lack of refrigeration facilities in Manila delayed its local use until almost a decade later.

The earliest known dog policy of the US in the Philippines was issued in 1899. With the aim of licensing dogs, especially in Manila, “this measure had nothing to do with rabies but to address the ‘nuisance’ of dogs’ ‘barkings and howlings,’ which ‘disturbed the slumber of citizens.’ Especially the American soldiers.

But some of these soldiers still took matters into their own hands, such as in Misamis Occidental, where the residents were scandalized by seeing native dogs shot everywhere. It led to the court martial of a Captain James Ryan, who had given the order for canine extermination.

The chapters on Sigbin (the aswang’s pet, or which it can even turn into) and Asong Gubat (the reputed “witch dog” with brinded fur) are ample in their contextualization within the matrix of Filipino folklore.

The Betsin chapter is amusing, even as it also allows for the introduction of strychnine as poison balls for street curs.

“Addressing the myths lurking around like the betsin-thingy is somehow gratifying. It’s like unlocking a piece of knowledge from the past that has been waiting to be released and shine its light on fake news-prone Filipino society. That Filipinos believe that betsin can kill a dog is a fragment of our national memory, which has been torn and crumpled, a memory of when street dogs were eradicated using mataperro, as the colonial authorities in the Philippines since 1861 had ordered it. This is why students must develop the skill of critical thinking as well as an appreciation of primary sources and historical methods. These competencies will help them discriminate against what is tsismis (hearsay). Knowledge of History is indeed power.”

With his indefatigability as a rigorous researcher, Alfonso deftly weaves a latticework of historiography, with its sustaining web of sources, cross-references, factoids and trivia. The author avers: “Although the book is entitled Dogs in Philippine History, it covers a wide range of topics: anthropology, archaeology, phylogenetics, folklore, ethnography, historical linguistics, art history, natural science, and religion. All these helped in shaping Philippine dog history.”

Jointly published by the Philippine Historical Association, Project Saysay, Inc., and Alaya Publishing, the book is available at the NHCP office or by linking up with bit.ly/AsoBookOrder