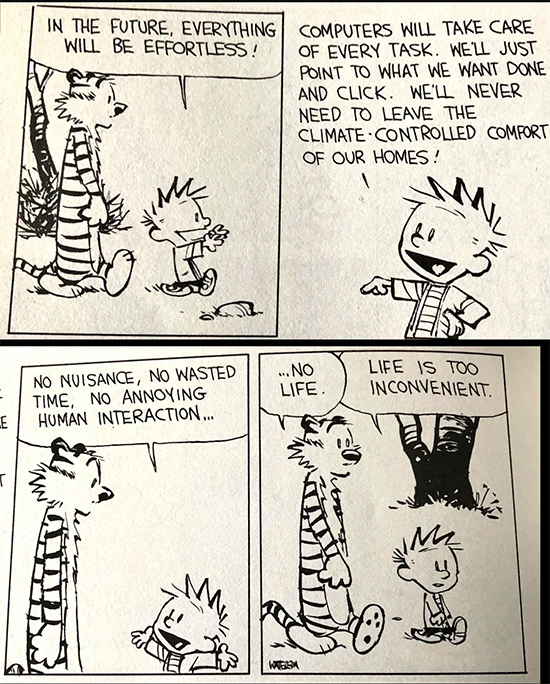

In praise of inconvenience

In one Calvin & Hobbes issue, Calvin goes on a short monologue: “In the future, everything will be effortless. Computers will take care of every task. We’ll just point to what we want done and click. We’ll never need to leave the climate-controlled comfort of our homes! No nuisance, no wasted time, no annoying human interaction… Life is too inconvenient.”

Four frames, each fully loaded.

Since seeing that comic strip, I’ve talked to some young people, mostly of the Gen Z crowd, to pick their brains on these thought-provoking Calvinisms.

Well, yes and no on things being effortless. Computers are a big help, for work, but cell phones are the real lifelines.

“I can’t survive a day without my phone,” said one researcher from a Catholic university.

She told me that one time, she left her phone in her father’s car and spent the whole day fretting he might see her private files (never mind that it has both numeric and biometric security), while constantly reaching in her back pocket for her absent phone like a sorely missed phantom limb.

A former colleague, who’s had three employers in as many years since getting his economics degree, equated his phone with his life: “It contains everything that matters to me—contacts, photos, e-wallets, mobile banking and ridesharing apps, games, social media, even my application letters and CVs.”

He smirked when I asked why he didn’t save them in an external drive or his laptop. “They’re backed up in the cloud.” Duh.

The Cloud. It’s better if you say it the way the Little Green Men chanted “The clawwww” in Toy Story.

For tech dinosaurs, the cloud is as esoteric as, say, 3-D printing or NFTs. So, I turned to some Gen-Xers for perspectives on an “effortless future.”

Most of them can’t quite wrap their heads around the genius behind touch screens, but they appreciate how they can order anything or book a ride online without leaving their La-Z-Boys.

“It’s liberating,” one retired friend said, “that I don’t have to rely on my kids, or my grandkids, for that matter.”

But these old-timers generally miss the golden days before call center menus and chatbots started messing up our lives. They lament that in this age of countless ways to communicate, there’s less and less actual conversation; one glance around the Sunday dinner table and you’ll understand what they mean.

In an unexpected move, the Zamboanga City government recently tried a “no phone weekends” campaign to force families to actually look at each other and use their outside voices while dining.

The initiative drew mixed results faster than a meme: some folks were thrilled about reviving the art of conversation (or convo for you Gen Zs) instead of having to sit through their cousin’s vacation slideshows. Others grumbled it was intrusive, impractical, and unfair; after all, what’s a family weekend if you can’t take group selfies or document every beautifully plated dish for Insta? Displeased Chavacanos might simply say: “¡Qué horror!”

It’s the missed trains, the awkward conversations, the canceled Grab bookings, the unexpected rain showers that drench our plans but give us stories to tell.

Evidently, real human connection feels rarer than ever. As the character San in the anime production of Princess Mononoke said, “I’m not afraid to die. I’d just rather not lose my humanity.”

Technology was supposed to make our lives easier and unlock our potential. But as the German philosopher Martin Heidegger warned, it can also trap us in a mindset he called “enframing,” a system that turns everything, including ourselves, into mere resources to be used. We’ve become “human capital,” constantly generating data that algorithms harvest, optimize, and sell. Along the way, we lose touch with real experiences and a sense of who we are.

It reminds me of the Pixar film WALL·E, where obese humans glide around on floating recliners, screens inches from their faces, oblivious to the beauty and mess of the real world. And in Netflix’s Black Mirror, every convenience in dystopian societies has a hidden cost: our data, our privacy, sometimes our empathy.

This age of frictionless living is not new in spirit. Erasmus warned us about it five centuries ago. In his In Praise of Folly, he mocked the vanity of those who believed themselves too wise, too refined, too efficient for human folly. Perhaps our modern folly is believing that convenience equals progress, that effortlessness is evolution.

Centuries later, Jun’ichirō Tanizaki explored this in In Praise of Shadows, grumbling how Japan’s traditional candlelight and aged patina were being replaced by Western modernity’s harsh gleam. For Tanizaki, true beauty existed in shadows, imperfection, and the quiet interplay between light and dark. The same could be said of modern life: In chasing brightness and clarity, we’ve lost the shadows that give human experience its necessary depth.

And then there’s Bertrand Russell, whose In Praise of Idleness dared to suggest that the cult of busyness was a trap. He argued that leisure — the freedom to think, create, and simply be—was the true measure of civilization. It’s hard not to think of him when we see people panic at a few minutes of unoccupied time, reaching unconsciously for their phones as if silence were a void to be filled.

Perhaps Calvin (not John Calvin, the Swiss Protestant Reformer after whom the rambunctious and inquisitive boy was named) was right all along: Life is too inconvenient. It’s the missed trains, the awkward conversations, the canceled Grab bookings, the unexpected rain showers that drench our plans but give us stories to tell.