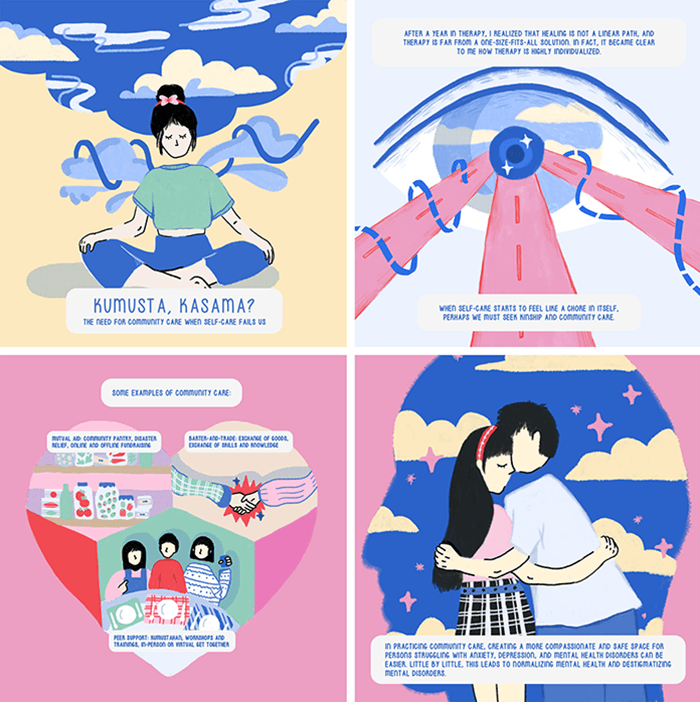

What does community care look like?

From a young age, I was hyperaware that I was overly independent. It was instilled in me to wear independence like a badge of honor, and I was praised for being so good at it.

My personal achievements did make me happy, but I knew deep down that I wanted to celebrate my wins or share how my day went with my favorite people.

Fortunately, even during the peak of my depressive tendencies, I still found warmth and connection. Finding friends and mga kasama to look out for each other was life-saving. We simply checked how we were holding up with our struggles and reaffirmed that we had each other’s back. I remember we would also eat food with the money we pooled relative to what we could give.

But when the coronavirus hit, my depressive tendencies were exacerbated. It may be a little too late, but that was when I was finally allowed to go to therapy and was formally diagnosed with clinical depression.

The pitfalls of individualized wellness

After a year in therapy, I realized that healing is not a linear path and therapy is far from a one-size-fits-all solution. In fact, it is highly individualized.

This individualization of therapy overemphasized my personal responsibility for my overall health. It alienated me for a time and it made me think that the only way to get healed is to bear the brunt of my drawbacks on my own. It also led me to think that I am competing with other people’s sicknesses.

While therapy can be a vital tool for personal growth, it may intensify our impressions that we are incapable of causing harm to others, thus possibly escaping accountability and blaming others.

It may also encourage us to view relationships as stepping stones toward personal gains. The individualized nature of therapy may emphasize what others can do for us rather than the values of giving, nurturing, and being present for others.

I recognize therapy as a helpful tool for a lot of people. Yet I see it more as a Band-Aid solution. It is ultimately a Western practice that may only be effective for a short period within the collectivist Filipino culture. The majority of Filipinos also cannot access therapy services because of poverty and stigma.

So, when self-care starts to feel like a chore in itself, perhaps we must seek kinship and community care.

Community care is a way of challenging the status quo, especially in a world where systems of domination persist and relentlessly offer seductive power over others.

The case for community care

Caring for the community is deeply ingrained in Filipino culture. This is evident when we meet someone new and seek a commonality, or we when describe our relations with others by attaching the prefix “ka” like in kapamilya, kaibigan, and kasama.

Mental health practitioner and writer Gabes Torres said that community care could take the practice of pakikipagkapwa as a response to the desire to connect and empathize with others. For instance, it could be listening to a friend, hosting an open mic for a community, or a mutual aid network of a community pantry.

She noted that it is hard to measure or narrow down community care into one definition because of “how fluid and flexible it can be” as “it varies in iterations, expressions, and scale.”

At its core, however, community care means caring for each other and recognizing one’s needs and limits. It means caring for people because we see them as humans with rights and dignity.

Torres and psychologist AJ Sunglao agreed that community care does not need much resources to be sustainable. Community members only need a shared understanding of and a willingness to support each other.

“There's magic whenever the powers-that-be see people congregate and realize that is threatening to them,” Torres said. “Whenever we get together and have a shared understanding of what we can do, we can do so much with that collective spirit.”

This collective spirit is what makes people flourish even in repressive circumstances. Having people we can cry and laugh with, discuss fears and dreams, or share doubts and shame with renews the meaning of our existence and connects us with purpose and happiness.

Creating an inclusive, compassionate future

For Torres, one way to ensure people with lived experience of mental illness are involved in the community is normalizing mental health and destigmatizing mental disorders.

“We've got to be able to meet (people with mental illness) where they’re at and understand and not judge or characterize them as defective or unable to participate in these movements,” she said.

She emphasized that education helps create a more compassionate space for persons struggling with anxiety, depression, and mental health disorders.

Likewise, Sunglao underscored that people with mental illness must not give up easily in finding their community. He said, “One community might not be able to provide every kind of care you need, but it doesn't mean that community is bad or unhealthy for you. It just means that you might need (another) community that can provide (a certain) kind of care you're looking for.”

With this, those who do not connect with their communities of origin might feel alienation and isolation when traditional sources of support, like families or religious institutions, reject them. Seeking community care within political communities can be crucial in sustaining well-being.

Connection as liberation

In All About Love, bell hooks wrote about the love ethic: “Concern for the collective good of our nation, city or neighbor rooted in the values of love makes us all seek to nurture and protect that good. If all public policy (were) created in the spirit of love, we would not have to worry about unemployment, homelessness, schools failing to teach children, or addiction.”

Connecting with living beings to build a better future together is human. I used to perceive this as a weakness I had to overcome. But the truth is this was a reflection of my authentic self—it goes beyond myself and recognizes our shared struggle and humanity. I just had to love myself for being honest and vulnerable, one day at a time.

Although some of us still struggle to find a tribe, our desire for connection is human. Community care is a way of challenging the status quo, especially in a world where systems of domination persist and relentlessly offer seductive power over others. More than that, community care serves as a reaffirmation to ourselves and the world that we deserve our self-worth, hopes, dreams, and love.