A plate of lasagna, a dash of Filipina charm, and my 40 wonderful years of public service at the Department of Finance

How was I to know that a 30-day appointment renewed twice would lead to a government career spanning 44 years, 4 months, and 3 weeks?

It all started in the '70s with me helping out two classmates get to where the Department of Finance (DOF) was and it was not the building on Agrifina Circle, but the one located in the new building of the then Central Bank of the Philippines on Mabini Street, in front of the then spanking new mall in Manila—Harrison Plaza. Neither of my friends knew how to get there via public transportation and commuting was one of my early life skills.

Then, fate approached in the form of one of the young clerks there who handed me a blank application form. I turned it away saying that I was not an applicant; only my two friends were. She said, “malay mo; fill up mo lang ito”. The next thing I knew, my friends and I were being treated to a lasagna lunch at the Italian Village restaurant in Harrison Plaza by no less than future NEDA secretary Manny Esguerra who, before he became a professor at the UP School of Economics, worked at the DOF. I credit him as my DOF recruiter. The lunch and the interview that followed were more like recruitment events, and not really a gauge about our fitness to work in the office. It’s a good thing that the lasagna tasted divine.

Don’t sleep, look intelligent, and always use the Oxford comma.

And that’s how my four-decade career as a bureaucrat at the DOF started. With a plate of lasagna.

I started working at the DOF on June 9, 1977, less than two months after graduating from UP. Of course that didn’t mean I got paid in the same month, or the next month either, even if my appointment status expired after the first 30 days, and was just extended. The second 30-day appointment was about to lapse when finally the Civil Service Commission granted me a one-year appointment.

Everybody in the office, from my first boss, then DOF assistant secretary Victor Macalincag, to Reynaldo Palmiery, who headed the Planning Service, my direct boss, Butch Javier, to the rest of my colleagues were ecstatic that I finally got my civil service professional eligibility. They were so happy for me that I could not get to tell them that SGV has just informed me that my long-ago application has been approved and I could report to work as soon as possible.

At one point being the youngest and also the most junior in the office, I got assigned to do a variety of jobs, from compiling statistics for information memorandum of bond issuances, reviewing bond prospectus and loan contracts, and computing net present value of projects.

The Philippines had the dubious distinction of being the only ASEAN country negotiating a deal with the Paris Club.

But I also did more menial tasks such as photocopying documents, preparing meeting agenda documents (including writing of minutes), and acting as a messenger to deliver loan documents to ADB or requests for legal opinion to the DOJ. I was young and all this work was interesting.

With our office then being small, we were assigned to attend inter-agency meetings, whether or not we actually knew anything about the topics. I would call it a sink or swim kind of mentoring that I received at the DOF. And at the end of every meeting we had to write a report about it. The times being in the late '70s, that also meant having to cajole or sweet-talk one of the three secretary-clerks to type out my long-hand reports. Years later I would try to do the same training with younger staff with these instructions: don’t sleep, look intelligent. Even much later I issued a 3rd rule: always use the Oxford comma.

Our salaries and benefits at DOF were then as now, nothing compared to that of our neighbors at the Bangko Sentral, to call it by its new name, or BSP for short. However, what we did have before was an ample opportunity to travel and that would be one perk that never grew stale over the years.

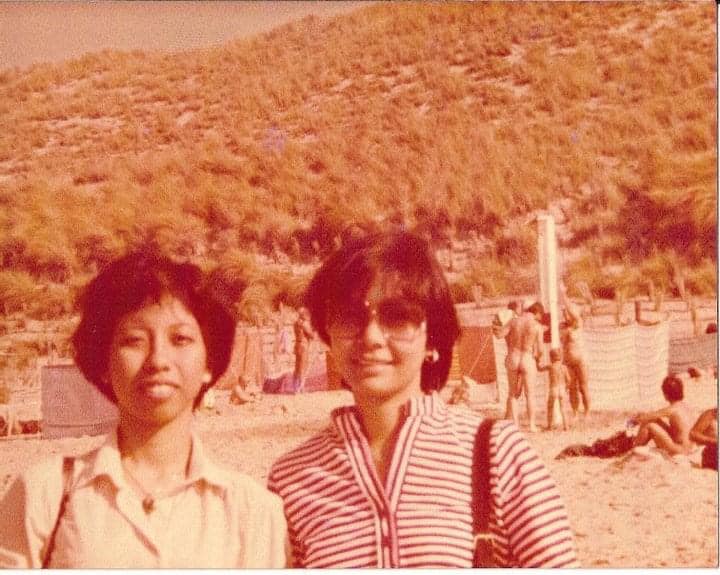

Thanks to DOF, I got a scholarship which funded a masteral degree at the Institute of Social Studies in The Hague, The Netherlands. Studying at the ISS was a character-building exercise. There were tons of reading for each subject and many days filled with being homesick. Lectures on winter days could put you to sleep and writing a thesis demanded a significant amount of personal discipline. On the plus side, I made lifetime friends among the Filipino scholars I was with at the time, and together we enjoyed breaks on student budget tours to Paris, London, Germany, and Scandinavia. Oh, and we conservative Filpina students also got acquainted with the dubious delights of the nudist beach in Scheveningen. The first photo I sent the office from The Hague almost made my boss apoplectic; I was posing with a friend on the beach and behind us all too clearly were naked men and women.

Then sometime later, reality kicked in.

In October 1983, the Philippine Finance secretary wrote our creditors to politely inform them that the government will not be able to pay principal repayments that were falling due on the various foreign loans which the country has incurred. The government would continue to pay interest payments however.

Thankfully for us, no story ever came out of it. It was a missed scoop for that newspaper.

That day started months of intense negotiations with all Philippine creditors—bilateral institutions and multilaterals like the World Bank and ADB—private banks, bondholders, suppliers, contractors. Many were listed in the register of creditors at the Bureau of the Treasury and the BSP; some were not.

If you worked in government then, specially at the DOF, BSP, and the Bureau of the Treasury, you would have become familiar with creditors claiming payments for loans that were not in our books, for government guarantees that were not registered but were covered by full powers from the President authorizing officials to sign. And then knowing that your database was not complete, the government team had to endure meetings with these creditors, negotiating the terms of rescheduling of the debts. The Philippines had the dubious distinction of being the only ASEAN country negotiating a deal with the Paris Club, which is a group of officials from major creditor countries.

It would have been easy to describe us as mendicants then, but the Philippine team was composed of dedicated career people who never gave up on their love of country, never gave up their pride as Filipinos, fought for each and every target included in those agreements with the IMF, bargained for easier terms for the rescheduled loans. We did not beg; we fought.

Much later on in the '90s, I became part of the team facing economists from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) who were tasked to ensure that monetary, fiscal, and financial reforms were being undertaken. Why was this scrutiny necessary? The Philippine creditors needed the IMF's seal of good housekeeping to keep on extending loans to the country.

An IMF team was always underfoot every quarter. Before they came, they always sent ahead a multi-page questionnaire for the Philippine authorities to respond to. This was always confidential and we took care that it was not among the stray documents that nosy reporters can read upside down. One time, as we were busy preparing our responses to how well (or not) we met our revenue projections for the period, we received a phone call from a newspaper desk. Somebody in our staff mixed up the last two digits of a fax number, so that instead of the questionnaire being sent to DBM, it landed in the office of one of the more well-renowned business papers in the 90s.

Our collective hearts stopped mid-beat, and we must all have turned a nasty shade of pale. The colleague who answered the phone was thankfully quick-witted, and with a nonchalant voice told the fellow on the other end to discard the missent document in the trash bin. Thankfully for us, no story ever came out of it. It was a missed scoop for that newspaper.

It would have been easy to describe us as mendicants then, but the Philippine team was composed of dedicated career people who never gave up on their love of country, never gave up their pride as Filipinos, fought for each and every target included in those agreements with the IMF, bargained for easier terms for the rescheduled loans. We did not beg; we fought.

We solved that problem fortuitously: we shared the table for lunch with the Mexican resource person and we introduced ourselves as coming from the Philippines. Faced with the charms of four Filipinas, he was completely disarmed.

We have gone a long way from those days, and it was less because of the kindness of creditors and the IMF, but because of the reforms that the Philippine government had undertaken through the years, the tenacious belief of the Philippine team that we could do this, we would overcome, and for the most part we did.

If I were to look back at the last four decades, the lows in my DOF life, I can count just a few.

One was attending a 1985 ASEAN conference on debt management held in Pattaya. Only the Philippines among the ASEAN countries had a serious debt management problem, and we were described as the only Latin American country in Asia because of that. This point was made very clear by the resource person from Mexico who kept repeating that on all economic indicators, ASEAN countries were doing very well that is, except for the Philippines. The four delegates from the Philippines, which included me, felt like hiding our country name plate and rebooking our flights back to Manila as soon as possible. We solved that problem fortuitously: we shared the table for lunch with the Mexican resource person and we introduced ourselves as coming from the Philippines. Faced with the charms of four Filipinas, he was completely disarmed. From that point, he never mentioned that dreaded phrase “except for the Philippines” again.

Other low moments came close to home: interminable budget hearings and advocating for reforms. I once got home from a plenary budget hearing on the DOF budget at 2 am and then at an 8 am breakfast meeting I was presenting details of our proposed sin tax reform program to an audience of civil society organizations.

This camaraderie has sustained us, and is actually one of the strengths of the bureaucracy.

Those experiences taught me patience and persistence. They have also brought some of our greatest joys and feelings of accomplishment. I also made some of my dearest friends in government because of budget hearings and our various tax reform advocacies.

There’s nothing like being thrown together for those hearings, whether for the budget or for tax bills, that make you feel like foot soldiers fighting in the trenches together. This camaraderie has sustained us, and is actually one of the strengths of the bureaucracy. At one time, we called ourselves who met every budget season as distinguished colleagues of the “ Committee of the Hole,” patterned after the Committee of the Whole in both houses of Congress. Actually, when I first heard that committee referred to during the initial years of our budget hearing saga, I actually thought that the word was really “hole” and always wondered why.

Advocating for reforms exacts a more exquisite kind of pain and requires endurance. One has to understand that the process of reforms is not a sprint but a marathon, if I may paraphrase DOF Sec. Carlos Dominguez in another context.

When the stars align, there is much rejoicing among the bureaucrats, especially when it is a victory against well-entrenched interest groups.

Sin tax reforms which would have indexed tax rates to inflation, unified the tiers, and removed the classification between old and new brands took almost 15 years and 4 presidents. Rationalization of fiscal incentives and rice tarrification were reform ideas that began in the late '80s. In between the time that these and similar reforms were crafted, so many man-hours (or in the case of DOF, mostly woman-hours) would be spent on studying the proposals over and over again, and scenarios will be built upon scenarios. Sometimes a reform bill makes it through the entire legislative process and gets signed into law; and you look at the provisions, bow your head, and sigh, my brainchild has become a mutant. After a period of mourning, we simply hunker down to work and try once more.

Yet when the stars align, there is much rejoicing among the bureaucrats, especially when it is a victory against well-entrenched interest groups. Such was the feeling when the Sin Tax Reform of 2012 and the TRAIN Law of 2017 were passed. Despite these milestone wins, we still maintain vigilance because at anytime in the political process, the winds can blow against us and if we do not watch out, hard-fought changes can be easily overturned.

The author with incumbent Finance secretary Carlos G. Dominguez III (center) and NEDA director-general Karl Chua during a meeting with economists. Photo by Howard Felipe / DOF

When asked in an international seminar I attended midway in my career at DOF how I would describe my work, I said, I spent the first five years of my job negotiating loans with various foreign creditors, then spent the next five years dealing with the same set of creditors and some more, in long drawn-out loan rescheduling meetings, and would probably spend the remaining years of my career at DOF finding ways how to pay for these loans. How prescient indeed! To think it all started with a plate of lasagna.