How the COVID lockdown hit different for migrant workers

For Yasmin Ortiga, a UP sociologist and Singapore Management University associate professor who has long studied issues of migration, education and work, the COVID pandemic led to many questions about how we value our overseas workforce—especially when they are suddenly “stuck” without an opportunity to earn.

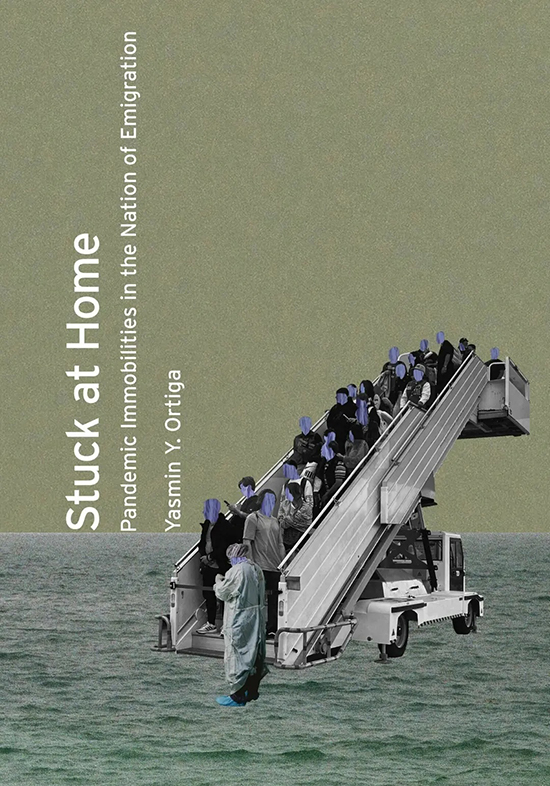

In fact, she authored a book about it—Stuck at Home: Pandemic Immobilities in the Nation of Emigration (Stanford University Press)—which had a Philippines launch recently at the College of Social Sciences and Philosophy at UP Diliman.

In the book, Ortiga studies cases from two groups of Filipino workers—nurses banned from leaving the country and cruise workers who returned home after COVID-19 shut down the travel industry.

PHILIPPINE STAR: How did you become interested in this area of study?

YASMIN ORTIGA: I’ve always been interested in the question of how ideas about “desirable” or “employable” skill determines who gets to migrate and where people end up moving. This book came about during a crazy time when ideas about essential skill actually determined why people did not move or were forced to remain in place. I just thought it was important to write a migration story that was mainly about immobility.

Why did you focus on nurses and cruise ship workers?

These two professions represent two very different kinds of immobility. Nurses were made to stay in place because their skills were considered so essential to the pandemic response. Meanwhile, cruise workers were simply unable to move because their skills had become “dispensable” when global travel stopped to prevent the spread of the virus.

There must have been a cognitive disconnect—being constantly told they were economic “heroes,” yet not having their unique situation as overseas workers addressed?

There was definitely a lot of frustration and anger. I also believe there was an underlying feeling of betrayal. After being celebrated as “bagong bayani” and being encouraged to leave, suddenly nurses and cruise workers were immobilized, with little support from the state that had benefited from their remittances.

(In fact) both groups also faced a lot of judgment for their immobility. Cruise workers felt a loss of status with their sudden unemployment. Meanwhile, nurses were often criticized for wanting to leave the country during the pandemic. Many of them coped with this by turning to support networks and fellow migrants.

Does the “hero” label just end up placing more strain on these workers? Do they feel politically exploited?

I think so! And yes, many of the nurses I spoke to didn’t really buy into that healthcare hero logic. I’d like to note that even at the height of the pandemic, nurses in our COVID-19 treatment centers were still receiving their wages a few weeks late. As one interviewee noted, it’s not as if he can say he’s a “hero” and get exempted from his bills.

During lockdown, people coped by using online workarounds—food delivery, Zoom, SMS, etc. But the skills of nurses and cruise workers are very “frontline.”

Unfortunately, nursing and cruise work are forms of care labor that can never be replaced by technology. These are workers who have to be with the people whose needs they attend to. In this sense, the inability to move to their places of work cannot be solved by technology.

For locally based workers, staying home is the goal. But for migrant workers, it's the opposite: They're at home when they're mobile and working. When do they get to “mesh” socially with the Filipino community?

I argue that this is what makes “migration management” so tricky—and the Philippines is supposed to be the world’s model in handling this task. Most times, the Philippines can facilitate the outmigration of workers with the general acceptance of the Filipino public. Things only become complicated in times of crisis (like the pandemic) or when there are failures to protect migrant workers abroad. The book shows how it can also immobilize people when it is in the nation’s political or economic interests.

What, if anything, has the Philippine government learned from the pandemic lockdown?

In fairness, I think the Philippine state has good people determined to fight for migrant workers’ interests. The government now knows that it needs to put more resources into recognizing migrant workers’ skills upon their return. The plight of nurses during the pandemic has also renewed calls for better work conditions and a proper wage.

What was the main lesson you wished to share in your book?

In many ways, the book is not really speaking to Filipino migrant workers, but Filipinos in general. The lesson is that migration is not just about taking advantage of global opportunity. It’s also about balancing national interests with individual desires to better their lives overseas. And while immobility might make sense from a policy perspective, it is really the migrants who bear the burden of cancelled journeys and missed opportunities overseas.

* * *

Yasmin Ortiga is a faculty member at the School of Social Sciences, Singapore Management University. The launch was hosted by the UP Department of Geography, the UP Population Institute (UPPI), and the Philippine Migration Research Network (PMRN), with the support of the Philippine Social Science Council. This event was also PMRN’s contribution to the celebration of the Month of Overseas Filipinos.