Reclaiming ‘Bading’

I realized I was bading through other people's disapproval.

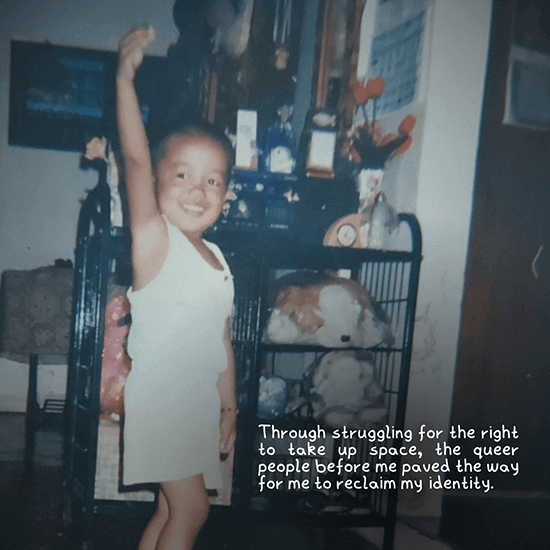

Before receiving scowls, tsk-tsks, and raised eyebrows for the Barbie dolls I chose to play with or for obsessing over Angel Locsin's Darna, my effeminacy and femininity were simply a state of being. I didn't even have a label yet for who I was, nor did I feel the need to have one, until the people around me started to maliciously interrogate me about my sexual orientation. Usually, an accusation and never an innocent question, relatives and strangers would ask me, "Bading ka ba?"

Since the badings I saw on the streets were usually made fun of and ridiculed, I learned at a young age to distance myself from the identity. Bading, bakla, bayot, and beki, usually interchanged by bullies, were words I never wanted to be associated with because attached to them were feelings of shame and guilt. In the streets, they were weapons used to humiliate. At home, they were warnings meant to keep me in check.

This led me to hate myself for who I was. On multiple occasions, I would fervently pray to a powerful being asking them to change me. I didn't want to be a bading who was the butt of the jokes. I wanted to be someone who didn't have to earn other people's respect and the right to exist. I wanted to freely pursue my happiness without being ridiculed and humiliated. Most importantly, I wanted to be someone who was not going to disappoint the people I love just because I didn't fit certain molds.

It pains me to think that this all happened at a time when I was supposed to be playing and having fun as a kid. While my peers were discovering who they were and building their identities, I was destroying mine.

Thankfully, I found community in the local queer sector, progressive groups, and the friends I met through the years. They embraced me and my kabadingan. Never mind that I found them a tad bit late in life; they still gave me a chance to get to know and love myself for who I am, which I didn't really get growing up. Through meeting people who were as bading as I was (maybe even more) and were extremely unapologetic about it, I was liberated from the shame that's been eating at me for as long as I could remember.

Suddenly, being bading, bakla, bayot, and beki was not so bad. They became badges of honor.

Courageously living our truths despite being told that we do not deserve to take up space is our defiance against an unjust system. Being a bading in a cruel world means choosing to love even after years of being subjected to hostility. It means finding beauty in what little the world and its history have offered us.

Queer history across the world is a story of violent erasure and persecution. In Nazi Germany, queer people were incarcerated in concentration camps for their queerness. In the United States, the lavender scare unjustly dismissed countless suspected queer people from their jobs. During the Spanish colonization of the Philippines, queer people were targeted and chased away. To this day, in many parts of the world, queerness is still criminalized.

In all of these cases, queerness is antagonized simply for existing.

However, our story is also that of resistance. The first revolts and uprisings against the Spanish colonization of the Philippines were led by babaylans and asogs, pre-colonial spiritual leaders who were counterparts of modern queer identities. When queerness was criminalized in the United States, it was queer women who threw the first bricks during the Stonewall uprising, the catalyst for the modern gay liberation movement. Today, some of the loudest and most brilliant voices in our fight for equality are queer.

Through struggling for the right to take up space, these queer people paved the way for me to reclaim my identity.

Reclamation is our way of reappropriating the languages that were used to hurt and dehumanize us. It is our protest against institutionalized oppression that turned us into pariahs. We are taking back our identities from years of trauma and societal stigmatization. By asserting who we are on our own terms, we are healing the parts of ourselves that have been besmirched by convoluted morals – morals that foster hatred and historically marginalized us and other groups simply because we were different.

There is nothing wrong with being bading, bakla, bayot, and beki. What is wrong is telling children that who they are is a mistake, and by extension that they don’t deserve to exist, and forcing them into years of self-hatred and pain.

Outside of people’s disapproval, being bading is our endearment to the parts of ourselves that deserve to be loved most. Unapologetically being ourselves is our celebration of centuries of strength, resiliency, and resistance. Bading, bakla, bayot, beki, and all the other words that were used to mock us, are our source of pride and unity.

Courageously living our truths despite being told that we do not deserve to take up space is our defiance against an unjust system. Being a bading in a cruel world means choosing to love even after years of being subjected to hostility. It means finding beauty in what little the world and its history have offered us.

Understandably, however, there are still members of the queer community that do not identify with these words. For them, these are still equivalent to reliving their trauma and abuse. While reclamation can be a source of empowerment for others, it's important to give everyone the space and time to heal their wounds.

Reclaiming our identities is part of a larger process of creating a world where we can thrive in diversity. Living our truths, in all our kabadingan and kabaklaan, is a way of promoting an environment where everyone feels safe to be who they are. Hopefully, by taking back our identities from the people who hurt us, we are building a future where queer kids are allowed to happily exist without having to fight for it.