Modern Makati 50 years hence and going forward

Like many young graduates of the 1970s, I started my professional life working in Makati.

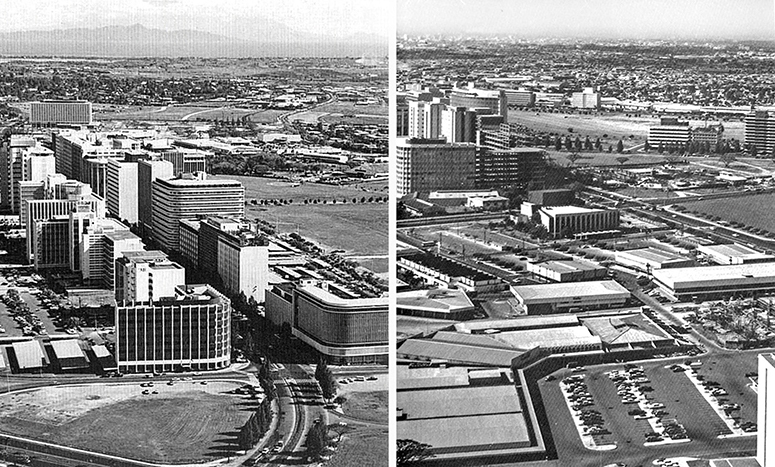

From our office windows, we could view what already was the premier Central Business District of the country. Behind us, Salcedo Village was only starting to fill up. Most of the taller 12-story buildings lined the two-kilometer stretch of Ayala Avenue. A few decades hence, Makati’s skyline has transformed to rival the best in the world.

This transformation is told in a new book published by the Makati Central Estate Association, better known as MACEA. The evolution of the Makati Central Business District (CBD) is the story of modern Philippine business, as told within the frame of a visionary master plan. This vision was fulfilled through the collaboration of its main developer and property owners representing the top business institutions of the country. MACEA is the embodiment of this collaboration.

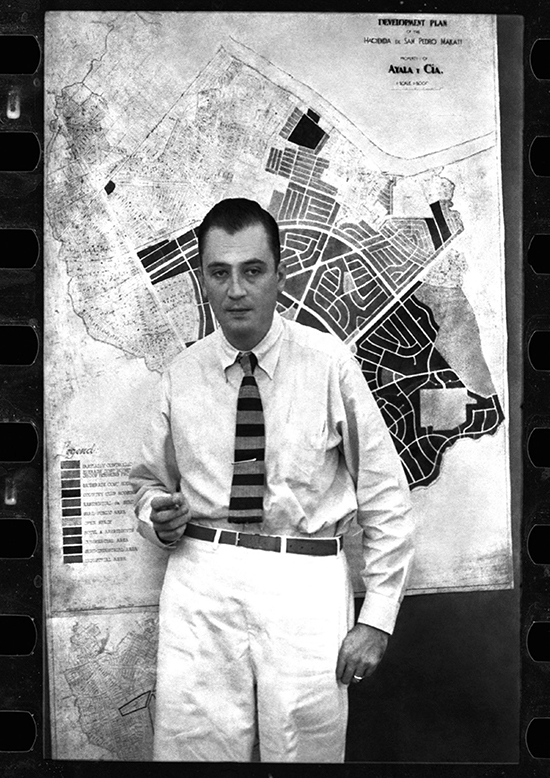

The book starts with three introductory sections. The first, by Fernando Zobel de Ayala, chairman of Ayala Land Inc., also concurrently the president and CEO of the Ayala Corporation, credits the current vibrancy of Makati, as well as the success of Ayala Land’s enterprise, to the vision of Col. Joseph McMicking. It was a vision that, together with fellow pioneers Alfonso Zobel de Ayala and Col. Jaime C. Velasquez, produced the master plan that Makati assiduously followed from the late 1940s to today.

Zobel de Ayala notes that the Makati CBD master plan worked because of three key elements. First was zoning, a concept from the US that dedicated spaces to housing, light industrial, retail, commercial, and recreational activity. Next was the strategy of phasing development to allow for continuous improvements. Finally, he highlights the essential role that MACEA played in the district’s governance.

The next section was penned by architect William V. Coscolluela. As chairman and president of MACEA, he narrates its saga, from its birth in 1963 with just 39 members to today’s 390-strong membership.

Coscolluela cites the association’s key role in “upholding the standards and policies established by (the Makati CBD master plan).” He also notes MACEA’s partnerships with the City of Makati, as well as the Ayala Corporation. This allowed MACEA to achieve its goal of safeguarding the interests of its landowners, of achieving an environment of prosperity, and solidifying the reputation of Makati as the nation’s premier CDB district.

The third section, Makati Through the Years, gives readers a concise chronology of Makati’s evolution, from the Hacienda de San Pedro Makati of the mid-19th century to today’s premier business district. The place’s history is of course intertwined with that of the Ayala Corporation that developed it, and which had its start in Casa Roxas, the precursor of Casa Ayala—the oldest business house in the Philippines.

The book tells the story of modern Makati in three main chapters. Each chapter is authored by Lisa Nakpil, whose elegant prose provides a singular and consistent voice. She provides a narrative that is easy to follow, but substantive enough for those in the know. Her text is beautifully augmented by fantastic images, both archival and current. I took great interest, especially in the black and white photography of Nap Jamir from the ’50s and ’60s, as well as the contemporary and dramatic documentation of the district’s landmarks from the ground and from the air by Wig Tysmans and his associates.

The first main chapter narrates the genesis of today’s Makati based on the foundations that started in the late Spanish-colonial period. This gained impetus after the devastation of the Second World War. Post-independence Philippines needed a new financial capital in 1946 and this was laid out in a visionary master plan by Col. Joseph McMicking.

This master plan introduced rational planning through the concept of zoning. Residential “villages” were established to provide needed housing, not just for executives and captains of industry, but also for an expanding middle class. Forbes Park and the various villages built from the late 1940s to the 1970s formed a greenbelt that surrounded a business district that grew from 12-story buildings on Ayala and Paseo de Roxas Avenues to today’s skyscrapers that rise district-wide. The chapter presents fascinating black-and-white images of the district’s beginnings as a tabula rasa pricked by the first few multi-story buildings of the Monterrey Apartments, the Insular Life Building, and the Rizal Theater.

The photo montages in the book continue with a showcase of the many layers of architecture, from the ’60s international style, to the post-modernism of the ’80s and ’90s, to today’s “green” buildings that tower over central spaces of the Ayala Triangle Gardens and the two green oases in the midst of Legazpi and Salcedo Villages.

The book also highlights the district’s emphasis on access and mobility. In 1997, MACEA started a Pedestrianization Plan to make the CBD a walkable district via an elevated walkway system, underpasses, and improvements of existing sidewalks. Over the last two decades the association has built 1.2 kilometers of elevated pedestrian walkways, eight underpasses, and improved kilometers of sidewalks, re-paving these with granite and modern pavers to make it comfortable underfoot, while planting native trees to provide welcome shade.

Today the system, as shown in the book’s pictorials, is an extensive network intertwined by parks and open spaces, including the Triangle Gardens, the Legazpi Active Park, Washington SyCip Park, and Jaime Velasquez Park. In the last few years, these have been augmented by 50 urban patios, welcome nooks recovered from underutilized road infrastructure, and which provide safer crossings between street corners. These have then led (especially since the pandemic) to the creation of “parklets” that allow al fresco dining on key streets like Rada and Esteban in Legazpi Village, and Leviste in Salcedo Village.

The whole pedestrian system is made more navigable by an innovative “way-finding” system that provides clear and readable information for passersby to get to their destination.

The second chapter deals with Communities & Narratives, showcasing the softer side of a district more outwardly defined by glass, steel, and concrete. Countering this, Makati CBD’s mise en scene is made more distinctive by an embarrassment of riches in public art and sculpture. Monuments figurative and abstract, along with murals and installations, are found in key public and private spaces. The works of Arturo Luz, Ed Castrillo, Jose Mendoza, Impy Pilapil, Peter de Guzman, Leeroy New, and many others make traversing the district outside, indoors, and even underground (via fantastic ceiling murals) a gallery-like experience enjoyed by everyone.

This enjoyment is made more complete because the district also offers a wide range of cultural, as well as culinary delights.

Makati CBD hosts several performance venues, from the now historic Insular Life auditorium to the 450-seat Carlos P Romulo Auditorium at the RCBC Plaza. Complementing these are the Yuchengco Museum and the Ayala Museum. Other venues host seasonal art festivals, while open spaces like the Greenbelt Park and Triangle Gardens offer perfect backdrops for art installations and celebratory displays.

Until the 1980s, one had to get to the Makati Commercial Center to dine or drink. The advent of mixed-use zoning from the 1990s onwards has brought a wide range of options for the best in F&B district-wide. Hip cafés and al-fresco dining are available on select streets, while gourmet menus to tickle high-end tastes are offered in dozens of penthouse destinations.

The Makati lifestyle was made more complete over the last few decades with the introduction of high-rise living. The Philippines’ first high-rise condominiums were introduced along Ayala Avenue in the 1960s. They are now distributed throughout the district, helping redefine the whole area as a complete live, work, and play city.

But complete, the Makati CBD is not. With MACEA’s guiding hand, the district is still evolving and improving. The book’s third chapter paints an exciting picture of the future. This vision of the future echoes the mantra of “relevance, resilience, and responsiveness.” This is shown best in MACEA’s communication and transport infrastructure projects, starting with an enhanced fiber-optic network for world-class connectivity. The district is also in the process of connecting to new subway transport networks that are already being built.

The book ends with a chapter on sustainability that follows international protocols for green building. It presents a final pictorial featuring a slew of new towers and complexes in varying stages of planning and construction. These include the Ayala Triangle Gardens Tower 2, the new BDO Campus, the Alveo Financial Center, the 54-story Estate Makati, as well as the BPI Head Office Redevelopment at the corner of Ayala and Paseo de Roxas Avenues—all taller, shinier, and more modern.

The book clearly presents an avenue to the future, as well paved by MACEA. Jaime Zobel de Ayala noted in 1975, “Anticipation of the future is based on the past—and on the present. The elements of yesterday serve as the foundation of today and the direction of tomorrow… Ayala Corporation could not carry out the entire project alone. The support of others, individuals and firms alike, was necessary. Those who believed in the credibility of our projects willingly joined forces with us. With them—and also for them—objectives were attained.”

The quote and this book clearly acknowledge the main force for the district’s development is channeled through and embodied in the Makati Central Estate Association. It is an invigorating force that will fuel the district’s even more progressive transformation in the next 50 years.