Ghosts in the machine

The dust may have settled after the recent elections. But not the ectoplasm.

For Pio Abad, whose ongoing exhibit at Ateneo Art Gallery, “Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts,” lays out a “forensic” accumulation of artifacts tied to the conjugal Marcos rule of half a century ago, this means looking at the world, post-2022 election.

“To be honest,” Abad says via email, “at the moment, I’m oscillating between despair — 36 years after their disgraceful exit from Malacañang, the Marcoses are back — while on the other hand, the elections also awakened a civic passion and an urgent need to safeguard history.”

Abad’s parents Butch and Dina were Ateneo activists and trade union organizers during the Marcos years, incarcerated in a military camp and put under “campus arrest” at Ateneo for a year after their release.

This has led Abad to examine the legacy of those years — a narrative threaded through his own family’s story — in numerous art exhibits worldwide. Accumulated and altered artifacts are interlaced with wry, often ironic commentary. The Ateneo exhibit, on display until July 28, is the culmination of 10 years of his archival “research” and was intentionally launched just ahead of the recent elections — perhaps to give people an extra moment of reflection before May 9. We all know how that went.

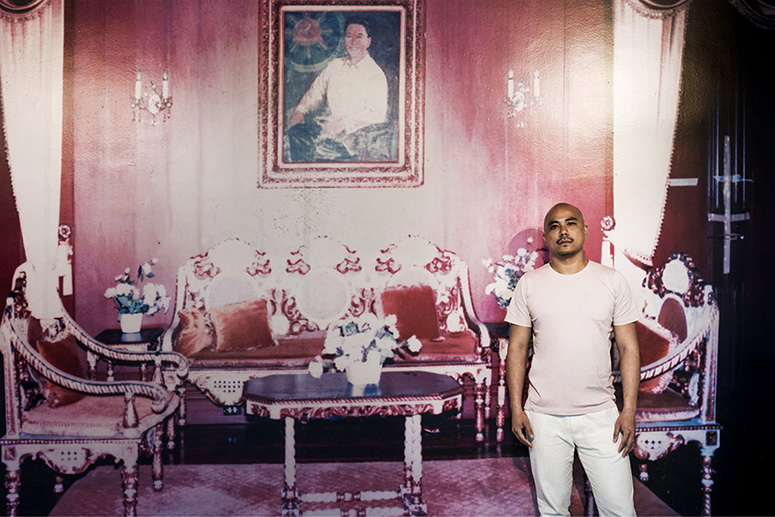

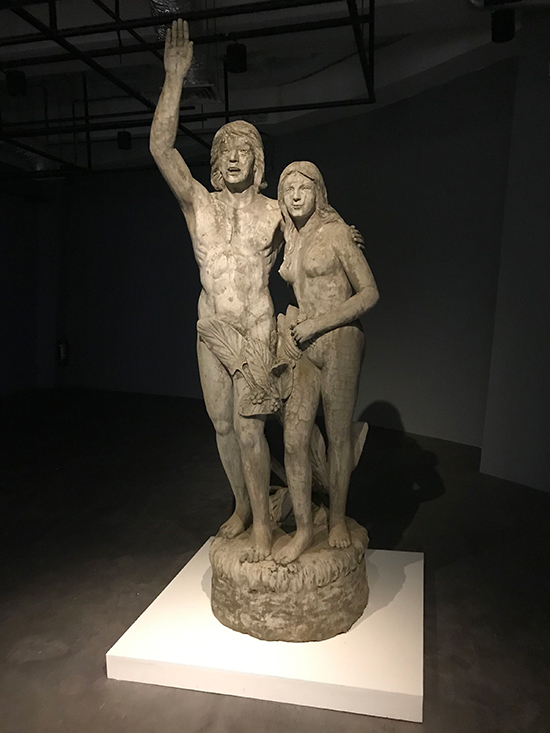

There’s an eerie feel to the three-room show — not surprising, considering its title. You enter upon a darkened chamber where plaster sculptures of mythical Filipino figures Malakas at Maganda, bathed in overhead light, occupy your full attention. On one wall is a vintage photo of Abad’s parents, standing inside Malacañang Palace before a portrait of Ferdinand Marcos in “Malakas” mode, taken on Feb. 25, 1986, shortly after the Marcos couple had been spirited away by helicopter.

The myth-making imagery pervades the opening room — from the video of an artist assistant painting over copies of similar Malacañang portraits with a black paint roller (the blacked-out copies are now displayed in the exhibit) to an actual copy of Si Malakas at Si Maganda, a limited-edition book from 1970 outlining Filipino creation myths in the guise of fanciful Ferdinand and Imelda portraits by artist Leonardo Cruz.

One of the most tragic flaws of the Filipino psyche is our collective inability to distinguish fame from infamy, which has led us to the political culture that we currently have.

The second room, bathed in white, is dedicated to the collections of “Jane Ryan and William Saunders.” Many will note those were the names reportedly used by the Marcos couple when they opened four Swiss bank accounts at Credit Suisse as early as 1968 and deposited an initial $950,000. This room is devoted to images of recovered antiques and baubles, artworks and Regency-era silverware — as Abad notes, it’s an attempt to “disentangle” the individual objects from their collective identity, laying them out “in a forensic fashion to confront the public with its unwieldy scale and terrifying range.”

At the center is a display with stacks of postcards depicting artworks that have been “sequestered from Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos and sold by Christie’s on behalf of the Philippine Commission on Good Government,” as the brochure explains. Among them, images of Goyas, Grecos, Old Masters; on the back are news articles tracing the migration of the artworks through the ‘80s, ‘90s and beyond. Visitors are encouraged to grab a handful; but as Ateneo Art Gallery director Boots Herrera recalls, at the opening, one artist friend felt a bit shy about scooping up so many. “She got a batch, but was a bit uncomfortable, holding that thick a pile. And I said, ‘It’s okay, don’t worry; Imelda was not worried about it, get some postcards.’”

I asked Abad if this emphasis on luxury, along with the mythmaking that seemed to link the Marcoses to Russian and even Egyptian royalty, was a method of seducing the masses with excessive baubles and riches.

“One of the most tragic flaws of the Filipino psyche is our collective inability to distinguish fame from infamy, which has led us to the political culture that we currently have. I think this cognitive dissonance has been brought about by a lack of time for complexity. Given the harsh realities of poverty and day-to-day living in the Philippines, the sorry state of education, you understand why these seductive facile representations are so successful in dominating the discussion.”

He adds: “The appeal of the Marcoses has always been about the disavowal of complexity. ‘Malakas at Maganda’ were uncomplicated archetypes. ‘Unity’ is an empty word made appealing through soundbites.”

It strikes me that cognitive dissonance is the new normal for our times. Two contradictory realities are somehow asked to co-exist in the same public space, in our minds, together. People are asked to accommodate competing sets of facts — to force themselves to believe that both can be true.

It’s a dissonance we see now in America, where many people somehow still believe that Joe Biden isn’t actually the person residing at 1600 Pennsylvania in Washington, DC, and some even go so far as to claim Donald Trump is still actually flying around the world in Air Force One, running things from behind the scenes.

Meanwhile, in the Philippines, Reuters reports many concerned Filipinos post-election were buying up textbooks, history books from local bookstores, in fear that they would be wiped from the shelves — and collective memory — forever.

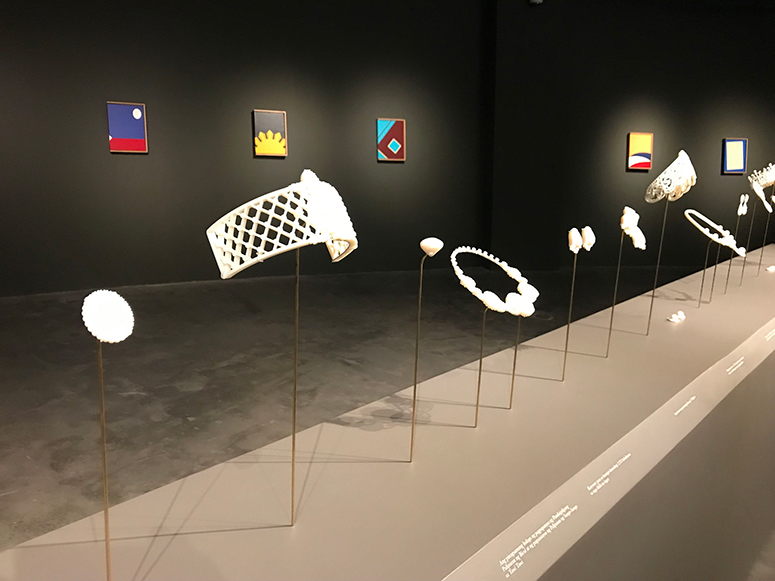

The final room of Abad’s show is extra eerie: fiberglass versions of confiscated Imelda jewelry float in a black space. The walls are lined with framed artworks — actually policy textbooks printed under the Marcos presidency — but the titles and slogans have been stripped off to reveal the original bold, modern graphic designs, some by famed artists, beneath. In a way, it’s an erasure meant to reverse the erasing of personal memory under those years. For Abad, it’s an ongoing battle: “The next six years will be a battle against erasure. It will be a battle for truth against a political machinery intent on inflicting full historical amnesia.” His next project? Gathering archival material from the Marcos/Reagan years: “It was a meeting of four minds (Ronald/Nancy/Ferdinand/Imelda) that recognized the power of weaponizing myth for personal and political gain.”

Cognitive dissonance. How do you treat the problem? How do you get to what some call “unity” when the side that has experienced the horror is being told, by the other side, that there’s no evidence, that it didn’t happen, you can’t prove it. How can those two very opposing viewpoints of reality ever be “unified”?

Of course there is an impulse in Filipino society to simply forgive and, if you have a particular cognitive ability, to actually forget.

But even this forgiving and forgetting requires an acknowledgment by the other side that there is actually something to forgive and something to forget; even this basic acknowledgment of reality is denied to the side that is asked to do all the heavy lifting.

* * *

Pio Abad’s “Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts” is at 3rd Floor, Ateneo Art Gallery, until July 28.