Artist and filmmaker Bea Mariano on noticing

It took Bea Mariano eight years to finish her undergraduate thesis at the University of the Philippines Diliman. While taking time to finish college is no longer uncommon, the artist and filmmaker says it wasn’t a conscious decision.

As an art studies major, her thesis expounded on the representation of indigenous people in Philippine paintings. It involved looking at a deluge of colonial photographs, which got her ruminating about ethics and representation. “I had an inordinate amount of anxiety, and I was in a lot of grief at the time,” she shared.

I felt like I had to pry her about this—the themes she explores and the centrality of slowness and taking the time in her practice—when we met at Silingan Coffee in Cubao to talk about her experimental short film Dominion with Young STAR.

“I'd like to think now that a lot of it was unconscious. Maybe that was my way of surviving,” she stressed. “There's a difference between taking one's time judiciously and being unable to. But it's also okay if that's how it's happened. It's like I've already had my quarter- and midlife crises, so I'm advanced in a way.”

Mariano’s film was recently named a finalist at the Gawad CCP Para sa Alternatibong Pelikula at Video under the experimental category. Before this, Dominion had its Philippine premiere during the recent QCinema International Film Festival under the SEA Shorts Program. (“I learned all of the films in that lineup were Philippine premieres,” the filmmaker remarked. “What does this actually say?”)

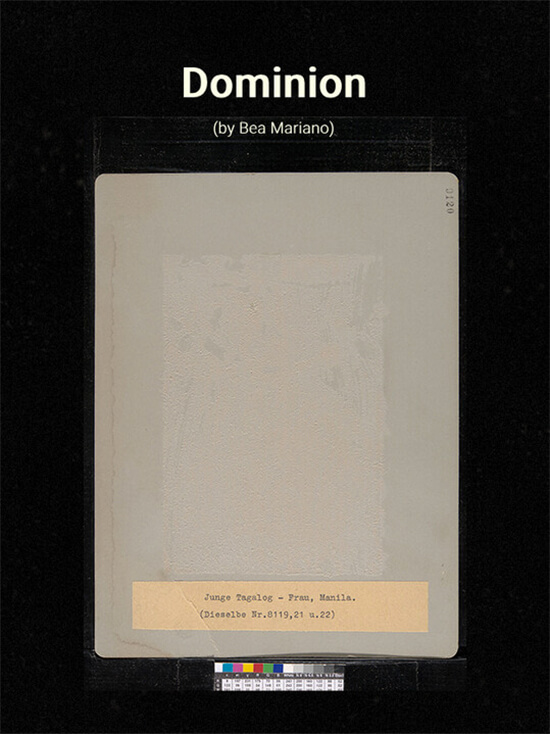

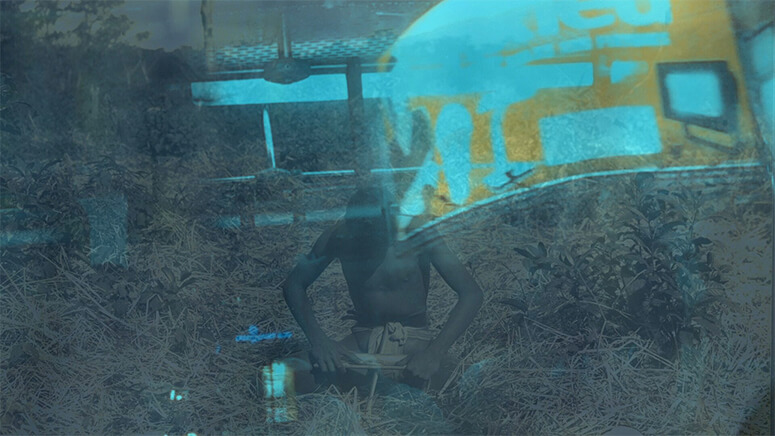

In the short film, which runs precisely for 7:11 minutes, Mariano—who is also a poet and an active member of the artist collective RESBAK (RESpond and Break the silence Against the Killings)—meditates on the power of images and the continuing reverberations of colonialism in today’s historical and cultural moment. She does this by stringing together colonial photographs and overlaying them with moving images and field recordings gathered from her personal archive that depict contemporary life. In this aspect, the film creates and pays attention to the inextricable connections between the past and present.

There’s an overwhelming quality to Dominion as one is bombarded with haunting photographs that allude to the powerlessness of early Filipinos. To this “jagged reverie,” a persona voicelessly narrates their experience going through these photos but digresses a lot to notice a cockroach in the sink, to talk about mango as big as the persona’s face. Towards the end of the film, the persona jumps into the cave.

“I usually try to 'capture' things around me and then later on use them in my work, which is what happened here,” Mariano explained. She was wearing a no-frills gray shirt and fitted jeans, like a minimalist who tries to assuage chaos with contemplative order. “I guess if I were more in the right headspace at that time, I would've approached it for elegance and quiet. But this time, I wanted to let people feel as overwhelmed and ‘out of time’ as I was.”

I caught the short at a special screening at the Ateneo Art Gallery. I initially swore to catch the lineup at the film festival, but life kept throwing another deadline or personal shenanigans to think through one after the other. I had this in mind as I finally watched Dominion: how futile and almost impossible it is to think through something, to arrive at a conclusion, when you are bombarded with digressions and the demands of life. I latched onto that morbid quality of examining attention in the short film, both delighted and intrigued by narrative shifts. Thankfully, Mariano delivered a talk at the gallery to discuss her breakthroughs in assembling such loaded photographs.

Mariano confessed that Dominion is only an incidental film, a project born out of her digital fellowship with Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum in Germany. The museum houses an extensive collection of colonial photographs, and she was chosen to do something with them in line with the museum’s effort to democratize access, especially to those from the Global South.

Initially, she set out to create an online journal poised to become a “node for access.” “I wanted other people to react to it and make their own works. And I mean people outside Manila, people outside the intelligentsia, the intellectual class. And then I wanted to put it online.”

Due to time and logistical constraints, it remains a work in progress. But, as fate would have it, Mariano’s fellowship overlapped with an invitation from Los Otros, a film lab in Quezon City, to make commissioned work. “I felt like I had no choice but to make that film,” the filmmaker revealed.

It seemed indicative of the organic quality of her artmaking process, which is grounded in her thematic preoccupations materialized by expressionistic responses to external and intimate impulses. The lack of “voice” of the narrator speaks to this care of (re)presenting the subjects captured—literally and figuratively—by the photographs, and the captions burned into the series of images point to Mariano as a filmmaker who outside of art also transcribes, translates, and codes.

In the age of the attention economy, Dominion stands out in that it almost demands one to look—really look. “The work was experimental, inaccessible and so, so easily misunderstood. And works like that aren't supposedly shown in big film festivals. I knew when I submitted that it was very, very unlikely that the film would be selected and I’d forgotten about it,” she recalled.

When she got the word from QCinema that her film would be part of the lineup, it did not register with her. “Short of being angry, deep down, I think I was anxious because something I did was going to be seen and I was going to be 'seen' (or) exposed.”

“I was also sad because when I googled the other films, they were done collaboratively and by people who are really in film,” the filmmaker admitted. “When I was putting Dominion together, it was just me and takeout boxes in a room. And a lot of frustration.”

Prefacing with ambivalence, Mariano shared that the film was her attempt to unpack colonial trauma, the importance of history and looking back, and how this trauma affects us in the present, both on a collective and personal level: “We need to look at our colonial history, look into how our colonizers' policies and their ideologies and policies impacted, on a personal level, how we were raised and the way our branches of government, our military, even, were run.”

Mariano continued: “The remnants of colonialism are basically our postcolonial condition, right? So, what does it mean to be attentive right now despite that? But attentive to what? Maybe, ultimately, attentive to our nation? A better life?”

“It's hard to force attention,” she muses. “I also think it takes some effort to pay attention to the truth of a thing because we're sort of wired to want things to be a certain way.”

And, to this end, Mariano raised an important question: “It feels like everywhere you look, there's so much neglect in our country. Mary Oliver said, ‘Attention is the beginning of devotion.’ If the antidote to neglect is care and attention—which is not the same as beautifying things—how do we pay attention to our country?”

***

Watch Bea Mariano’s experimental short film Dominion (2023) and read about her present project dalumat, dalamhati, dignidad at https://www.dekolonyalidad.org/.