A century before Trump, did you know Mindanao and Palawan were almost swapped for Greenland?

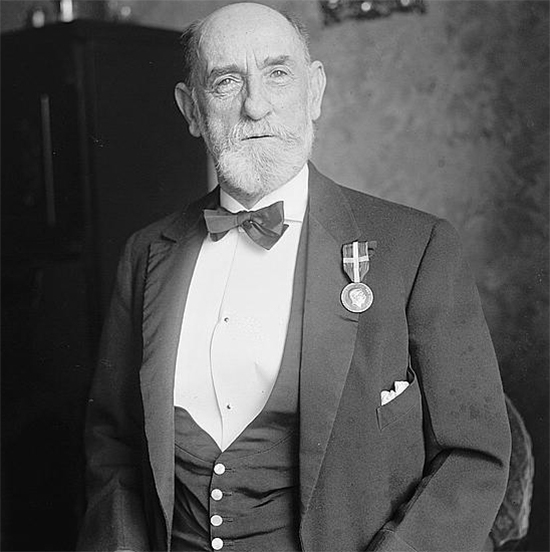

In 1910, US Ambassador to Denmark Maurice Francis Egan dispatched what he coyly described as a “very audacious suggestion” to Washington. On the grand imperial chessboard, he proposed moving three pieces at once. America, our then-colonizer, would give Denmark the southern Philippine islands of Mindanao and Palawan. Wow!

Denmark would hand over the United States Greenland and the sun-kissed Danish West Indies. And Denmark would then, in Egan’s imagining, pass the Philippine islands on to Germany, in exchange for the lost territory of Northern Schleswig.

It was a barter of breathtaking absurdity—a geopolitical three-card monte in which islands and their millions of inhabitants were shuffled like collectible trading cards between empires seeking advantage. The idea, thankfully, never progressed beyond a letter. Yet it reveals a destabilizing colonial mindset in which geography was treated as movable property and people were little more than footnotes on a deed.

This historical footnote feels less like a dusty archival curiosity and more like a stubborn, recurring dream in the geopolitical psyche—one that has recently startled awake.

The American fascination with acquiring Greenland, publicly revived and pursued by president Donald Trump, shows that the notion of territory as real estate never entirely left the strategic imagination.

The crucial difference between 1910 and today, however, is the voice of the people who call these places home. Modern Greenland is a semi-autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark, with self-government and a recognized right to determine its own future. Filipinos, too, would now rightly find the idea of trading our islands not merely offensive, but unimaginable.

The failed transaction and the play that never was

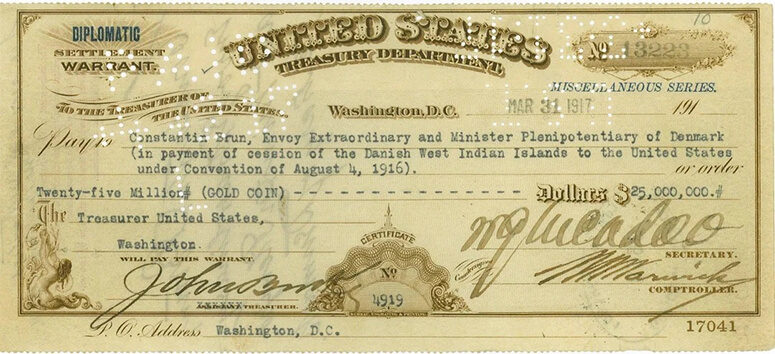

The proposed 1910 swap was fantasy, but America’s desire for Greenland was persistent. When the United States formally purchased the Danish West Indies—now the US Virgin Islands—in 1917 for $25 million in gold, the treaty required Washington to formally recognize Danish sovereignty over all of Greenland. It was a strategic bargain, not a romance.

Not to be deterred, the US made another secret offer in 1946 to buy Greenland for $100 million in gold. Denmark again declined, as if turning away an increasingly insistent suitor who could not take a polite no.

This history of islands as bargaining chips reminded me of my friend, the late banker and award-winning playwright Bienvenido “Boy” Noriega Jr. He once told me he was planning to write a play entitled Palawan.

In Noriega's imagination, the island would serve as a potential government-in-exile—a final redoubt if the Philippine archipelago ever fell to Communist rebels forces, like the Chiang Kai Shek regime fleeing to Taiwan province in 1949 after losing the Chinese Civil War in the mainland. There was no Vietnam or Germany style reunification, since the West defended the rebel regime on Taiwan as their key chess piece.

The Palawan play was never written, but its haunting premise echoes the logic of Egan’s 1910 proposal: an island imagined not only as a homeland with its own songs, forests, and sunsets, but as a strategic asset—a final chip to be played in a game whose rules are written elsewhere.

Indigenous wisdom — from the Arctic to the Cordilleras — has long challenged the arrogance and cynicism of treating land as a commodity to be bought, sold, or swapped by distant powers.

A Danish legacy of stories, not swaps

Perhaps it is fitting that the nation at the center of this proposed territorial swap is a kingdom built on profound storytelling rather than land deals.

From the Viking king Harald Bluetooth—whose name now invisibly connects our devices—to the existential philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, whose dense works I first wrestled with as an Ateneo college student, Denmark has exported ideas that shape how we understand the world.

Denmark gave us Hans Christian Andersen, who spun tales of ugly ducklings and little mermaids, forever championing the outsider. It also gave us Karen Blixen, who penned Out of Africa, a love letter to a land far from her native Copenhagen.

There is a deep irony here: while starched diplomats once schemed in wood-paneled rooms to trade islands like commodities, Denmark’s most enduring global contributions are its stories—tales of identity, belonging, and the human condition, which are not for sale at any price. Even Denmark’s famous butter cookies, traveling the world in iconic blue tins, have served as gentler ambassadors than any colonial treaty.

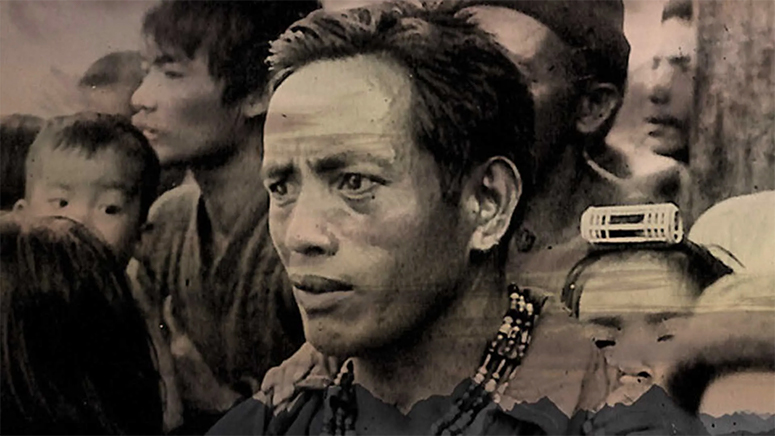

Another thought comes to mind whenever I read news about territorial disputes argued over heatedly by headline-grabbing politicians. The line, “How can you own the land when it shall outlive you?” is most famously associated not with a North American chief, but with Macli-ing Dulag, a Pangat of the Butbut tribe in Kalinga who opposed the World Bank-funded Chico Dam project in the 1970s. He paid for that resistance with his life.

The quote is often misattributed to Chief Seattle, but its true Philippine origin matters. It reminds us that indigenous wisdom—from the Arctic to the Cordilleras—has long challenged the arrogance and cynicism of treating land as a commodity to be bought, sold, or swapped by distant powers.

In the end, the 1910 proposal stands as a parchment testament to the folly of treating maps as ledgers for the accountants of empire. Palawan and Mindanao were never items on Denmark’s manifest, nor America’s to consign. They are, as they always have been, homeland.

And Greenland, despite acquisitive glances from distant capitals, answers only to the will of its people and the quiet authority of its ice.

The most hopeful lesson from this bizarre historical sidebar is that while empires plot swaps, the people—like the steadfast characters in a great Danish fairy tale—ultimately, and stubbornly, write their own endings.