Remembering River

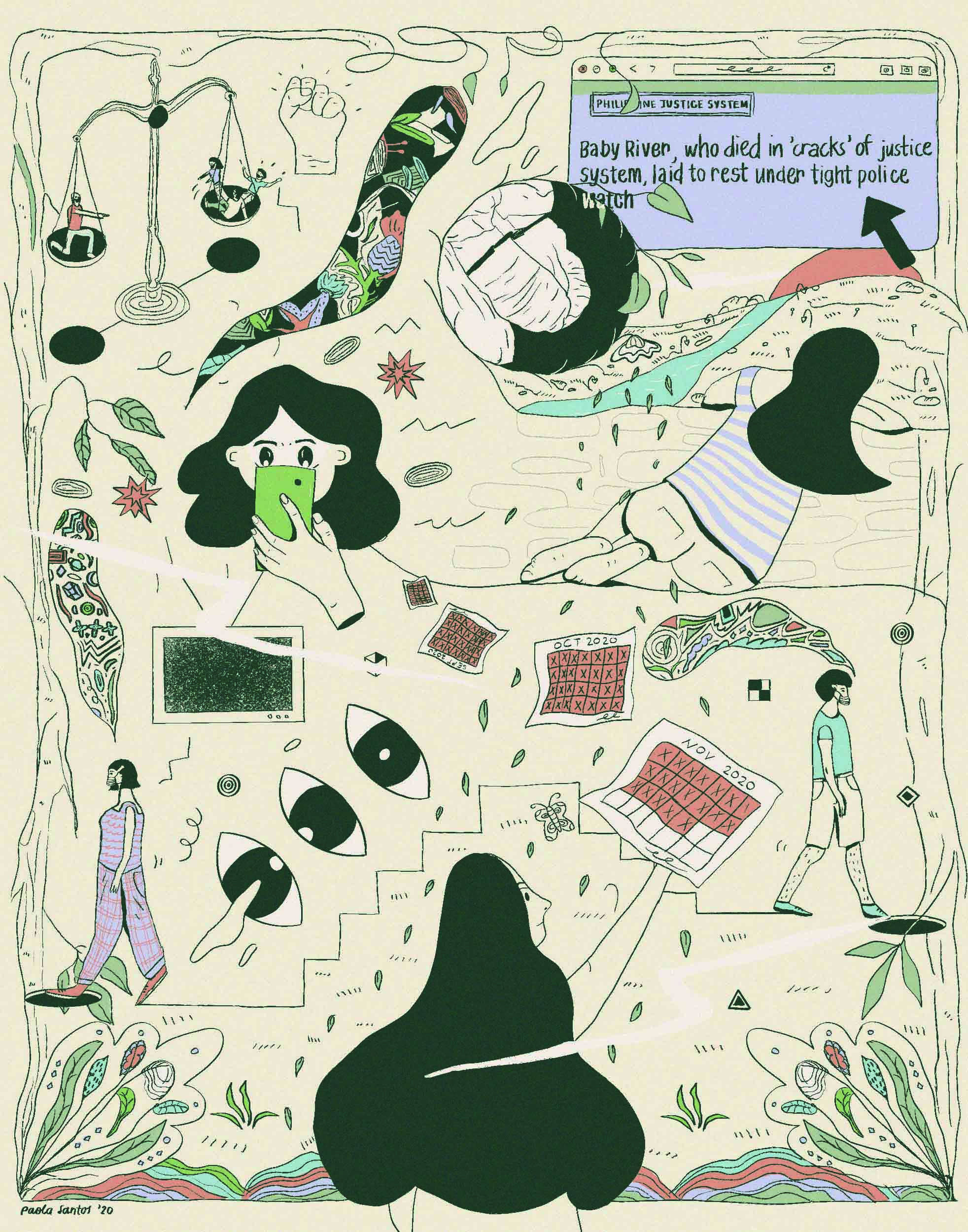

What’s three months to you? It’s the average length of an online module on Coursera.com, ample time to tidy up paperwork, or long enough to fall in and out of shape. Here I was, coordinating plans for the last quarter of 2020, trying to salvage a sense of normalcy from an already upended year. Then, on my phone, I stumbled upon an image. I looked twice before wanting to look away.

In the foreground is a lady clad head-to-toe in PPE gear, one wrist cuffed, both hands clasped onto the glass of a casket; a casket so tiny your heart will shudder.

This forlorn woman leans over the coffin. It’s maybe a foot wide, not even two feet long. A uniformed man’s rifle frames the photo’s left-hand corner while other armed men crowd around. This is the sight of 23-year-old detained human rights activist, Reina Nasino, laying her daughter, three-month-old River, to rest. Authorities would later attempt to take the grieving mother away, 20 minutes before her meagre three-hour furlough was over.

What’s three months to you?

For River and her mother, it’s a sentence too long; a lifespan too short.

Baby River’s passing is unlike other reports flooding our feeds. Hers is not a COVID- or calamity-related death, but one attributed to lapses in our justice system. It’s no surprise this hits hard, amidst a time when a certain degree of (media) desensitization is expected.

Baby River’s death is a staunch reminder that the Philippines has been fighting battles even before the pandemic plagued it. Prior to the outbreak, there have been decades of uproar over injustices, dissent over investigations left open and court appeals untended. Before this era of frontliners, certain individuals likewise championed human rights the best way they knew how: as activists. River’s mother is one of them. Sadly, she and her fallen infant were not accorded the same respect given to more high-profile political prisoners.

Fact: We’ve been practicing social distancing even before the pandemic required it.

I’m talking about the societal divide so shamelessly seen in the disparity of treatment for detainees. How is it that a former first lady, proven guilty of graft, was granted reprieve due to her old age and health condition, while a three-month-old baby born of low birth weight was not allowed to remain with her detained mother despite the physician’s prescriptions? Moreover, how could a former governor convicted as mastermind of a harrowing Mindanaoan massacre be granted furlough to attend his relative’s wedding, all the while Reina Nasino was given no more than a six-hour window to visit her child’s grave and mourn with dignity?

Thoughts like these leave me distraught... and that’s okay. These days, I’ve learned there’s no such thing as a right way to feel, even if there are still wrong ways to act. That anxiousness, anger, misplaced guilt, or whatever confluence of emotions are burrowing inside, proves we are letting ourselves actually be concerned for others when it’d be so much easier not to care. If you are the slightest bit disturbed about what’s going on, then, at the very least, it means your humanity’s still in check.

I’d never felt more unnerved by the sound of cellphone notifications than I did in mid-May. Every ping signaled a barrage of disheartening news — 104 tested positive in San Juan City, 50,000 in the entire metro, hospitals forced to turn people away, while frontliners turned toward danger. Learning the disease was airborne made things all the more suffocating, so to speak.

We all deal in unique ways, no method more or less valid than the other. Some of us self-soothe by watching lighthearted material online or picking up a hobby. Others prefer virtual catch-ups, internet discourse, or even random mood-boosters (shout out to the TikTokers of Manila). For me, I resorted to a bit of space and (radio) silence. I stayed off social media as much as my work would let me. I stopped reading news altogether for some time. Many friends shared the sentiment that they’d had to press pause on consuming media so the distress wouldn’t hamper their own efficacy. After a few weeks of this cleanse, I gained a deeper understanding of my threshold and need to cope. This came with a sharpened idealism for how to contribute in my own way as a creator and coach.

I realize now my self-imposed “break” helped me guard against what experts call “compassion fatigue” (a.k.a., the lessened ability to empathize after unchecked saturation from negative news). Sometimes it is necessary to disengage if only to clear our heads. A little distance doesn’t mean you’re emotionally distant or indifferent; just that you’re recouping as needed.

Every now and then we can give ourselves the mental space to step back, introspect, and accept the things we cannot control while redirecting our efforts productively into things we can. Realize we’re each primed for actionable compassion.

As we probe into how 20-somethings can make a significant impact, some helplessness is bound to kick in. Even beyond COVID, singular efforts seem futile against systemic ills that outlive generations. Fair point.

I counter doubt by thinking of current and aspiring frontliners. Students and practitioners who stay the course instead of deserting their degrees. They channel their grief into grit, bolstered with renewed vigor. They aspire to give back so the world can move forward.

I quell fear by reclaiming my sense of agency and remembering I’m a first-string player, on the frontlines of my life. We all are. We’re weathering our own storms, scarred yet enduring, channeling the gratitude for life into our best efforts to live it.

The pandemic has mired us in a period of prolonged global grief. We’ve all been mourning someone or something, soldiering on for nearly eight months now. It’s not uncommon to feel the normalization of tragedy, as painful as that sounds. Yet River’s death prompted me to confront all the carnage the disease and the decades of injustice has cost us. Writing this gifted me with a sense of peace, with a readiness of not only moving on, but of moving forward.

In honor of baby River and all those we’ve lost who’ve yet to be vindicated, the least we can do is make the most of ourselves as human(e) beings. Take this as a modest invitation to revisit our sense of humanity, specifically the standards of it we practice in our own lives. Benevolence towards others and ourselves can be as simple as accepting when we’ve been wrong, and learning how to be better. “Unkind” is but a few degrees from “unfair” so let’s hold each other accountable. Our journey of evolving after all, is not a race but a story. Maybe this one (re)starts with Baby River... and all of us are co-authors.

I may not work in the government, nor do I see myself in law or medicine. I’m hardly “insta-famous” either! I’m just one of the many yuppies braving my own reality, six workdays, and the occasional K-drama at a time. What now? For starters, we drop the “just” and trust in the integrity of our proactive intentions. Trust that the innate empathy and resilience grief that has unearthed within 40 million or so Filipinos will ultimately cast more light over this sea of dark. Perhaps then we get to be, as River was and is, a vestige of hope.