In defense of dreaming ‘small’

When I still worked at the marketing department of an AI company, I used to slip out during dull hours to go to a café and read a book. I was, frankly, sick of the work—it turns out I passionately hated AI and hated marketing it even more—and I wanted to pretend, even just for a half-hour, to live the life I wished to have instead.

It wasn’t lost on me that I was extremely fortunate: The job paid me enough so I could put my brother through college. It enabled me to live closer to the office. I kept repeating to myself that what I did for work didn’t have to matter as long as it gave me financial freedom. It’s fine that it wasn't my dream job, as long as it paid for my dream life.

But when is a job just a means to an end, the key to the life I want, and when is it just my life? At what point does it start defining me? At the time, I was at the office for nine hours a day every single day. I thankfully had side projects that made me feel purposeful and were better aligned with the work I wanted to do. But most days I would be too exhausted from my corporate role, from the workload to the office politics, that I didn’t have time or energy to do anything but order takeout and scroll on TikTok. Was this the dream life I was so set on building?

A few years ago, somewhere in Gangnam District, a South Korean software engineer named Hwang Boreum had a reading ritual similar to mine. She recounted the story in the library of the Korean Cultural Center in Taguig last September, where her readers (including me) gathered for a talk and book signing. Boreum was in the country in time for the Manila International Book Fair.

Constantly working long hours then, Boreum felt she was losing herself—until she encountered a nearby bookstore. For the next six months, she ate her lunch quickly to spend most of her break reading books.

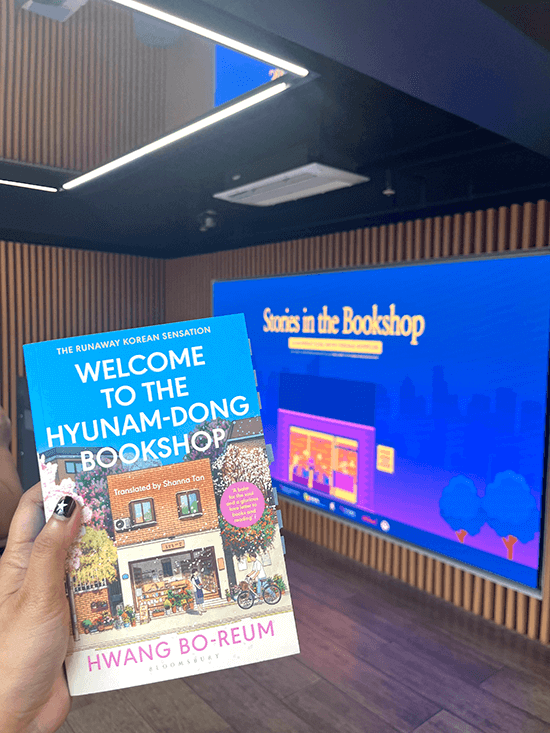

Soon, she quit her job and, at age 30, started writing her own books. You may recognize one of them: Welcome to the Hyunam-dong Bookshop, a bestselling novel about Yeongju, a woman who abandons her thriving career and bustling city life to open a bookshop in a quiet neighborhood.

“I’ve never aimed for a specific occupation,” Yeongju admits in the book. “I was just not interested in becoming a lawyer, doctor, or anything else. Neither did I want to be successful or famous. I just wanted a stable life. I mean, if I can be acknowledged for my skills in something, that’d be great, but that’s about it. I just wanted to be an independent person.”

“That’s a cool dream,” says Minjun, the bookshop’s barista, who is similarly disillusioned with career aspirations. He worked hard in school in hopes of a good job, only for it to never arrive.

Yeongju responds, “Not at all. It’s as if I don’t even have proper dreams.”

Like Yeongju (and Boreum), I filed for immediate resignation at my AI marketing job, partly out of mismanagement but mostly because simply thinking about the job drained the life out of me. I certainly felt relieved to get out, but also confused about what to do next. I didn’t have a five-year plan or a “proper” dream I wanted to work towards. Since childhood, I felt I was simply on autopilot, checking off the prerequisites for success: good grades, Latin honors in a big university, then a reliable corporate job. For the first time, I reckoned with the fact that the success I chased satisfied others more than it did me.

The rest of my generation is finding less and less fulfillment in climbing the ranks. A Deloitte survey this year found that only 6% of Gen Z and millennial workers see reaching a senior leadership position as a primary goal. Rather than a career ladder, many Gen Z prefer a “career lily pad,” where they get to hop from one opportunity or field to another.

On paper, it sounds lazy and entitled—criticisms that are not new to Gen Z. It’s as if people my age no longer know or respect the value of hard work. That’s what I thought at first, too. I didn’t see myself in the C-suite; I hated the idea of being a “girlboss.” For a while, I perceived this as a lack of motivation or ambition. Maybe I was simply a failure satisfied in my own stagnation.

Or maybe it was a natural response to the hopeless job market. To companies that always put profit above people and employers who push us into management positions with extra work but no extra pay and mentorship. Life is challenging enough—prices rise but wages don’t, and young adults now can barely afford to live, let alone buy homes or start families. Can we be blamed for dreaming of stability, of simpler, peaceful lives, during such tumultuous times?

Besides, I didn’t want to stop working entirely; I still had to provide for my family. Like the author Boreum, I wanted to write. But I was hesitant to fully pursue it because it was a bit of a demotion: it paid considerably less and would have no flashy BGC office. It would draw more raised eyebrows at family reunions.

During Boreum’s book signing, she said that her office job made her feel like she was “dying already,” and that each time she stepped into the bookstore during lunch hour, she was able to breathe. She said Yeongju, from her book, feels the same. So maybe there’s nothing wrong with my decision to take a moment to breathe, too.

When I quit my corporate 9-to-5, I didn’t have a next job lined up. I was intent on spending a few months taking back my life and writing a lot more. Of course, it was a privilege to even have this option: I saved up a bit, but I was still paying some of my family’s bills on top of my own. I knew this was a risk not everyone would be able to take. But I also knew I had no choice but to leave the job I had. When I worked in corporate, I barely saw my family anyway. When I did, I was miserable and exhausted.

It also wasn’t a perfect choice. I still work long hours to make ends meet, and even then I cut back on a lot to make it work. But at least I find what I spend my time on actually meaningful. I don’t have to cry in the office bathroom or lose sleep over small mistakes. This is something Welcome to the Hyunam-dong Bookshop portrays so thoughtfully: Your dreams should serve you, not the other way around. “(You) work for your whole life so as to earn the final few moments of happiness,” Yeongju says in the book. “To achieve happiness at the end of life, you have to be miserable for a lifetime. When I think of it this way, happiness becomes horrible. It’s such an empty feeling, to stake everything on a single accomplishment in life.”

Of course, my career contributes to my happiness. It fills me with purpose and pride, and assures me that I can continue helping my family. But it’s also not the only thing that makes me happy. It’s spending time with my loved ones, losing myself in a good book, writing a piece I’m really proud of, and knowing that my productivity does not define my self-worth. I’m not completely closing my doors on corporate, but now I have a clearer idea of what my dream life looks like.

I may no longer be a good and “successful” employee, but at least I’m finally a good and happy daughter, sister, friend, and person.

“A life surrounded by good people is a successful life,” the barista Minjun says near the end of Welcome to the Hyunam-dong Bookshop. “It might not be success as defined by society, but thanks to the people around you, each day is a successful day.”