Whatever happened to Project NOAH?

With the Philippines battered by an average of nine storms a year, it goes without saying that having reliable weather and disaster forecasting agencies is crucial to sustaining life and progress in our continually challenged country.

The question then of whether to end or continue a project seen to help avert disasters and save lives such as Project NOAH should be a no brainer, nor should it even be a question at all. So why did the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) opt to pull the plug? Just bad decision-making? Did they merely accommodate egos slighted by turf issues? Was there politics involved, in that the administration wanted to get rid of successful projects initiated by the previous administration? What happened, however, was more nuanced and overtly less political than many may have perceived it to be.

A catchword

The name Project NOAH came about during the tenure of DOST Secretary Mario Montejo, in line with an effort to brand the various projects DOST was funding under the ambit of disaster risk reduction.

“Ako nag-isip ng pangalan niyan,” said Raymund Liboro, who was then the de facto DOST spokesman being the head of the DOST- Science and Technology Information Institute (STII).

Liboro, who has worked in the media industry, said they aimed to establish “a catch word” that people could easily recall when talking about DOST’s various programs to enhance the country’s disaster preparedness. A “backronym,” NOAH stood for Nationwide Operational Assessment of Hazards and served as a refuge for the DOST’s different projects.

At that time in 2011, the DOST was already funding three research projects— ClimateX for better rainfall forecasts, weather sensors development, and the DREAM (Disaster Risk Exposure, Assessment and Mitigation) program for hazard maps.

“Circa 2012, all of us belonging to DOST-funded projects were met to put a cohesive and unified framework for all of the research we were doing,” said Eric Paringit, professor of geodetic engineering at UP and DREAM program leader.

The pressure to gather round and amplify the government’s disaster mitigation efforts was largely spurred by Typhoon Sendong in late 2011, which inundated Northern Mindanao, displaced thousands, and left over a thousand dead in its wake. During such time, the issue of climate change has also been gradually seeping into mainstream discourse driven by stories about efforts to cobble a new globally binding framework before the expiration of the Kyoto Protocol in 2012.

“The administration at that time thought that we have to put out a very good way to communicate to the public that we are doing something about disasters,” Paringit said.

Further adding pressure to the government to show it is doing something to prevent disasters that time, then President Benigno Aquino was also reported to have been partying during Sendong’s aftermath, an issue which blew up after a celebrity tweeted about the event.

Special order 595

DOST then sought to consolidate its three ongoing disaster-related research projects under one umbrella, and add more. This was when Liboro and Paringit brought onboard Mahar Lagmay, a geology professor at the UP National Institute of Geological Sciences, to help spearhead the project.

Project NOAH then formally came into existence with Montejo’s DOST Special Order 595 signed July 12, 2012.

“In order to facilitate the integration of the various interdependent disaster science research and development projects of the DOST, the Program NOAH is hereby established,” Montejo’s SO 595 stated, adding that the program will include the components DREAM-LIDAR 3-D Mapping, FloodNET, Landslide Sensors Development and Hydro-Met Sensors Development.

In its initial core, Project NOAH was geared to beef up disaster forecasting by the improvement and installation of additional sensor instruments, generation of more detailed hazard maps of the country’s major river basins, and further automation of weather forecasts that will allow expanded lead times. Included in its expected outputs from the start is the deployment of 80 automatic weather sensors, 100 rain stations, and 1,000 automatic rain gauges and weathers stations for the 18 major river basins. FloodNET, complemented by the WEB-GIS (Geographic Information System) component, is the front-facing project that directly interfaced with the public by interpreting data gathered from sensors to calculate flood potential.

Operational R&D

After inheriting three ongoing projects, Project NOAH quickly midwifed project after project to total 10 in a year’s time, each of which an independent creature of its own aimed to enhance the capability of existing operating agencies. But unlike traditional research and development programs, what set Project NOAH apart was that it was immediately operational from the get-go.

“Project NOAH was quite unique in that it was an operational R&D project. While it was researching and developing, it was also already operating immediately because its function was seen as critical to disaster mitigation,” Liboro said.

Carlos Primo David, who was then the project leader of ClimateX, said the gap during that time in weather forecasting and disaster risk reduction was readily apparent.

"The idea is to develop tools and data for us to be able to forecast weather, rainfall, where it will flood, and where the landslide areas will be and so on,” David said. “But very early on, we knew that the tools will not be a project forever because we will be transferring this to the mandated operating agencies doing such kind of work.”

The projects under NOAH were all headed toward improving the country’s disaster resiliency, but each moving part was autonomous. Many components of NOAH were in itself also temporary by design, like the distribution and installation of additional meteorological monitoring equipment to augment PAGASA ("Emergency Distribution of Hydrometeorological Devices,” "Development of Hybrid Weather Monitoring System). On its face, such a project cannot be done in perpetuity as an agency can only distribute so much hardware around the country without being overly redundant and wasteful. Others were event-specific and location-specific, like the program to map typhoon-devastated areas in Visayas (“Smarter Visayas”). Two components were also tech-specific, such as two projects allotted to the development of satellite technology (“PEDRO” and “PHL-MICROSAT”), in itself already sustainable given the DOST’s push to develop a dedicated satellite agency.

As a testament to the pressing need to put the word out there about the government's disaster mitigation strategies, there was also a separately funded component that served as the “marketing arm” for Project NOAH and was carried out by the DOST - STII.

Operational demands

Though Project NOAH eventually expanded to have implications for various government agencies like Phivolcs, NDRRMC, and local government units, bulk of the work was a souped up version of PAGASA, such as the initial centerpiece of putting out a six-hour lead time warning for floods and storms through ClimateX. So why didn’t PAGASA just do it in the first place? Here is an excerpt from the 2015 program report of Project NOAH submitted to the DOST:

“PAGASA has been the sole government agency that has the mandate to provide weather forecasts for the country,” the report noted. “Due to operational demands, the agency was constrained from conducting research experiments that may further enhance the forecasting capabilities of their numerical models.”

Project NOAH was a workaround to bureaucratic bottlenecks that may have hindered innovation and expansion for an operating government agency already burdened by and short-handed in its day-to-day affairs

David noted that PAGASA was already delivering services crucial to disaster response, only they felt “these services can be enhanced by automating some of the functions through computer programming through developed softwares."

Project NOAH in short was a workaround to bureaucratic bottlenecks that may have hindered innovation and expansion for an operating government agency already burdened by and short-handed in its day-to-day affairs. Project NOAH, however, was not a unique framework. The facility through which Project NOAH was funded is common enough that it often goes by the acronym GIA or Grants-In-Aid program.

DOST's commissioned research projects could then be seen as a way to improve operating agencies' capabilities while working around the government's conservative nature of fixed plantilla allocations -- that is, improve public service without adding to bureaucratic bloat by paying third-party troubleshooters to study and show how to improve things.

DOST's commissioned research projects could then be seen as a way to improve operating agencies' capabilities while working around the government's conservative nature of fixed plantilla allocations -- that is, improve public service without adding to bureaucratic bloat by paying third-party troubleshooters to study and show how to improve things.

Tightrope act

Of course, a third party parachuting into a well-established enclave to study, recommend, and even outrightly execute what could be a better way of doing things is a sensitive tightrope act as people normally do not want to hear outsiders telling them how to do their jobs better.

In our work, we have to find out and understand the gaps and limitations of an operating agency so it’s inevitable that you will say to them what are those gaps, which could be an issue at first for some

“In our work, we have to find out and understand the gaps and limitations of an operating agency so it’s inevitable that you will say to them what are those gaps, which could be an issue at first for some,” Paringit said. “Pero wala namang personalan. As scientists and researchers, we are just doing our work and that is to help things improve.”

A crucial distinction between an operating agency, like PAGASA, and a research and development program, like Project NOAH, is also manpower. At the back-end of the visualizations being generated in the Project NOAH website are tons of instruments that collect data and are installed in various parts of the country that need regular maintenance and calibration, grunt work that only an operating agency with established satellite offices in the country manned by personnel with developed expertise can manage.

“It’s not easy sustaining a vast monitoring network,” said Renato Solidum, Phivolcs director.

Phivolcs, which maintains instruments scattered across 92 locations in the country to monitor fault lines and other geologic activity, also adopted one Project NOAH component. This is the “Dynaslope, Senslope” program that enhances landslide monitoring by deployment of new sensors.

“To manage such a network you need sustainability, maintenance, and an operating fund, and that is lodged under government organizations with the mandate to look at and operate after such systems,” Solidum said.

“In other countries, I’ve seen the same models where research universities would do research to improve monitoring through tools and processes and then organizations would adopt,” Solidum added.

In the Philippines, the framework for such a relationship between the government and research institutions is laid down in Republic Act 10055 otherwise known as the “Philippine Technology Transfer Act of 2009.”

“The State shall facilitate the transfer and promote the utilization of intellectual property for the national benefit and shall call upon all research and development institutes and/or institutions that perform government-funded research and development to take on technology transfer as their strategic mission,” RA 10055 said.

Project NOAH’s transition of its initial projects in fact started way back in 2015 when Montejo signed SO 784 mandating PAGASA’s absorption of the project’s initial outputs.

Letting go

The technology transfer and eventual adoption of newly developed technologies could also be tricky. Not only should the recipient be made to fully understand its meaning and be sold on its value, but developers also need to grapple with a measure of apprehension in letting go of products they worked hard for.

“I think they (PAGASA) understand the gist of what NOAH does,” said Jo Brianne Louise Briones, a former Project NOAH research specialist. “But I don’t think they see na may kaba din on our part kapag na-turn over na namin sa kanila kung magagawa ba nila ito ng tama, or magagamit ba nila ito to what we envisioned it to be.”

That is not acceptable to me na mababa ang tingin nila sa aming hanay dito

The suspicion mounted to an extent that the PAGASA employee’s union almost staged a protest rally to show their indignation, only to be held off upon the request of PAGASA administrator Vicente Malano.

To assert their case, and their competence, PAGASA instead held a press conference on Valentine’s day 2017 with a tarp declaring "PAGASA is an institution. NOAH is only a project." The misgivings on the recipient’s part for the technology transfer then reached a boiling point.

“Yung tingin sa amin kasi they are more superior, yun ang hindi acceptable,” said Ramon Agustin, then the president of the Philippine Weathermen Employees Association. “That is not acceptable to me na mababa ang tingin nila sa aming hanay dito.”

A storied agency

PAGASA is one of the oldest government agencies in the country that was officially formed in 1972 but has had many previous incarnations tracing back to the Spanish occupation. It has a storied past, but also a wounded history.

It is not without reason that weathermen are often the butt of criticisms and jokes for their seeming unreliability. The science certainly has far progressed and developed since village folk used folklore to foretell weather, but reading the skies is still a discipline based on mathematical and scientific models, predicted outcomes that are in itself just that, predictions that could at a moment’s notice veer wildly off course. Highly specialized instruments could gather accurate data, software programs could crunch patterns and equations to deliver the likeliest scenario, but in the end, Mother Nature will still have the last word. This is the reason why there will never be a weather forecast with an infallible 100% accuracy.

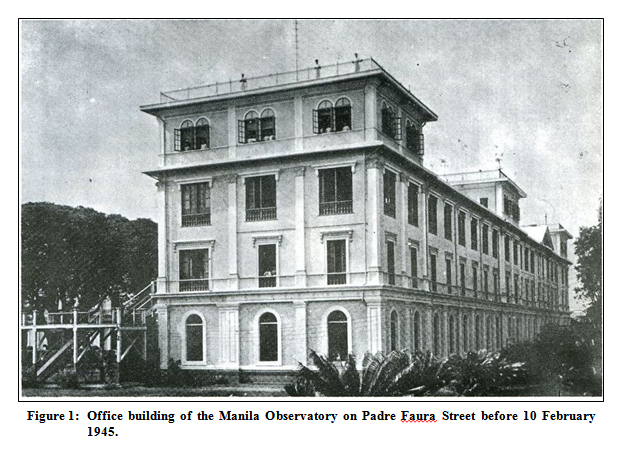

The Observatorio Meteorológico de Manila in Padre Faura was the earliest precursor of PAGASA. It was established in 1865 but was destroyed during the Battle of Manila during the Second World War (photo from PAGASA website)

This inherent limitation of the science came to a head a year before Typhoon Sendong, when Aquino dressed down then PAGASA administrator Prisco Nilo in full view of television cameras for failing to forecast that Typhoon Basyang would hit Metro Manila. Nilo was sacked by Aquino a few weeks after. During Aquino’s time, PAGASA would be headed by three administrators. This perceived inadequacy of PAGASA, at a time of outlier weather disturbances, as typified by Supertyphoon Yolanda in 2013, further catalyzed the growth of Project NOAH.

Because of the pressing and growing need, the government eventually pumped P6.4 billion into 20 research projects, 10 under the initial project pipeline, 9 under the expanded NOAH, and one as an extension project. For perspective, the entire funding is over double the P3 billion that PAGASA received for its modernization fund signed by Aquino in 2015.

Project ISAIAH

The last Project Noah component is Lagmay’s Project ISAIAH. In March 3, 2016, DOST Undersecretary for R&D Amelia Guevara wrote to Lagmay informing him of the DOST-EXECOM’s rejection of ISAIAH’s extension.

"It was noted that the proposal is a continuation of previously funded projects under the NOAH program, hence the financial requirements should be lower than the proposed budget. Moreover, the objectives and activities are not commensurate with the level of funding requested,” Guevara wrote.

The letter went to list recommendations that Lagmay could incorporate into another proposal, while noting that the GIA program "will be funding some of the proposed activities only.” The GIA funding for Project ISAIAH was then released through the DOST-Philippine Council for Industry, Energy, and Emerging Technology Research and Development (PCIEERD) for P24.5 million to cover activities from March 2016 to Feb 2017.

As DOST confirmed that the project is drawing to a close, incumbent DOST Sec. Fortunato dela Pena said that PAGASA is ready to accept 15 personnel from Project NOAH. Lagmay, however, was largely lukewarm to the idea, repeatedly noting his people are different from PAGASA

“We are not a forecasting team,” Lagmay said in a press conference. “We do not just look at the weather. We translate the weather into vital disaster risk information.”

Though Lagmay has initiated the transfer of developed technologies, he emphasized that his concern from the start was his people.

“We need to take care of our scientists because they need to eat too. They need to provide food for their children, give money to their children, money to buy milk so that is very important,” Lagmay said.

In an announcement last Feb. 23, the University of the Philippines heeded Lagmay’s plea and announced that they would “continue Project NOAH.” UP, however, did not specify what specific project components, and how much personnel, they absorbed.

All good things

David, who now heads PCIEERD, is optimistic the technology transfer worked. He said perceptions that PAGASA will not be as open as Project NOAH in terms of readily available data is also being looked at.

All good things must come to an end, but in endings also come new beginnings.

“As the funding agency, I will compel them to actually provide the same services, if not enhance it even,” David said.

Paringit, whose Phil-Lidar 2 project also winded down, said they have also transferred technologies they helped develop.

“We know that it will end as it’s just a natural course of research projects,” Paringit said. “We just see it as the next challenge because as an R&D practitioner we are ready to retool, look for other functions, and learn new things to enhance our products because otherwise we will just stagnate.”

Paringit said that they have also filed an application for extension of the Phil-Lidar program to map more far-flung provinces that have not been covered in the primary program.

"All good things must come to an end, but in endings also come new beginnings. There may be issues in letting go, maybe due to separation anxiety, but we just have to explore new possibilities. That is just part of growing up,” Paringit said.

(A previous version of this story first appeared in InterAksyon.com in 2017)