Kakanin: As Pinoy as it gets

It is a well-known fact that central to any Filipino meal is rice, whether for breakfast, lunch or dinner. But let’s not forget the countless rice-based snacks in between meals, be it savory rice noodles (pancit bihon gisado, palabok, Malabon, etc.) or the endless, sweet kakanin (rice cakes) found all over the archipelago.

Kakanin comes from the root word “kanin,” or cooked rice. The myriad of variants may come in different shapes, sizes and flavorings, from north to south of the country. More often than not, the same delicacy may be called by a different name in other regions, or, as it also happens, the same name may mean something else to others.

But what remains constant with this merry mix is they all share the same main ingredients: regular or glutinous (malagkit) rice (white or colored, whole grain, ground or flour); coconut milk and/or its meat (cream, grated, strips, candied, toasted); sugar (white, brown or Muscovado); and the same enduring love and passion it has been made with by generations of Filipinos over many centuries.

Kakanin has endured the test of time, sustaining us in times of abundance and scarcity, peace and war.

Kakanin has endured the test of time, sustaining us in times of abundance and scarcity, peace and war.

With the diversity of our regional cultures, languages, religion and cuisines, we Filipinos have more in common than we realize. Kakanin transcends all the boundaries of these diversities.

This popular sweet delicacy is as sticky as it gets, literally binding us together as one people, one nation. What’s not to love about these sweet rice delicacies, not to mention those made with cassava, taro, corn, millet, cornstarch and wheat flour?

Though these countless variants fall under the collective term kakanin, let’s categorize them according to the method they are prepared.

Let us count the ways.

Puto

Puto generally refers to steamed, sweet white buns, usually served with freshly grated coconut meat. It is often shaped like bite-size petit fours or the bigger cupcakes, or when cooked in large round pans, it is cut into trapezoids. Pre-soaked glutinous rice is ground (galapong) and mixed with coconut milk, white sugar and baking powder, often flavored with aniseed.

Some towns have become famous for the puto named after them: puto Calasiao (Pangasinan, left photo), spongy bite-size cakes; puto Biñan (Laguna), soft, steamed rice cakes often topped with cheese and/or salted egg; puto Manapla (Negros Occidental), baked instead of steamed rice cakes.

The white puto is not just eaten as is, but because of its sweetish taste and spongy consistency, it makes a perfect accompaniment to the sour, salty and mellifluous dinuguan or blood stew (left photo), and a wonderful counterpoint to the umami-rich noodle soup La Paz batchoy of Iloilo City (right photo).

Puto pao is a cross between the steamed sweet puto and the meat-stuffed Chinese siopao. The white puto pao is stuffed with pork asado or stewed pork, while the artificially colored violet one has ube jam (purple yam).

The bite-size putong polo/pulo is known to have originated in Barangay Polo, Valenzuela City. What makes it distinct is its reddish-brown color due to atsuete (annatto) and it’s topped with cheese.

It’s been so identified with the barangay that a Putong Polo festival is held every second Sunday of November annually. These bite-sized treats have a spongy texture and a sweet, buttery taste, with a tiny bit of saltiness from the cheddar cheese.

Puto kutsinta is a steamed, sweet gelatinous, semi-translucent rice cake served with freshly grated coconut meat. It owes its reddish-brown color to atsuete and brown sugar.

Cigar-shaped puto bumbong is traditionally a Christmas staple of the Tagalogs and Pampangos, originally made with a violet-colored glutinous pirurutong rice, placed inside a bamboo tube and then steamed. When cooked, margarine or butter is slathered over it then Muscovado and grated fresh coconut sprinkled over.

Its name is derived from the bumbong kawayan (bamboo tubes) it is steamed in. Nowadays, white glutinous rice is used, albeit artificially colored, mimicking ube or purple yam, which it has none of it actually.

The puto in Sorsogon (simply called puto) has candied coconut strips placed in its center before it is steamed. It owes its purplish color to the mixture of white glutinous rice and tapol, or violet rice.

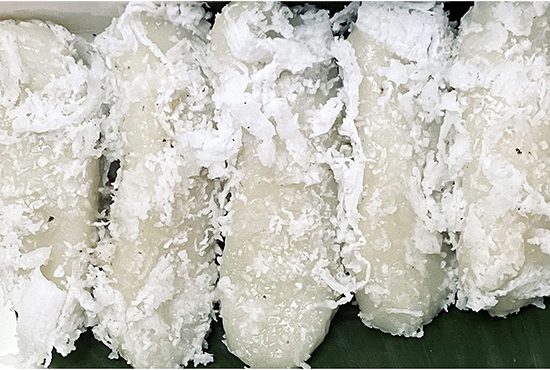

Palitaw is a sticky rice cake coated in freshly grated coconut meat. It starts with dough made with glutinous rice flour, shaped into elongated flat strips, dunked in boiling water, and then it floats to the surface when cooked, hence its name. A.k.a. pepalto or dila- dila (tongue-shaped) in Pampango; butangan in Muslim Mindanao, it is usually eaten with white sugar and toasted sesame seeds.

The Tagalog ginataang halo-halo or ginataan bilo-bilo is named after the marble-size glutinous rice balls cooked by themselves or mixed with other ingredients like saba banana, kamote, sago pearls, langkâ or ripe jackfruit, and ube. They are cooked together in a thick, sweetened coconut milk.

It is called sampelot in Pampanga and usually paired with inangit (see biko) for an afternoon merienda. Up north in Ilocos it is called pararusdos, while in Batangas it’s paridusdos or pinindot, and pinaltok in Laguna. In Cebu and Bohol, it is called binignit.

Mochi and Palitaw

The Japanese mochi has taken on a life of its own in many parts of the country. Using the palitaw dough as base, the Pampango mochi is stuffed with bukayong niyog or caramelized grated coconut. It is first dunked in boiling water then fried on one side to give its toasted brown surface. It is served with a thick coconut cream sauce.

Called oros-oros in Nueva Ecija, these ping pong-size boiled mochi are stuffed with caramelized grated coconut and served with a thick coconut cream sauce.

The mochi found in Cavite City is called bibingkoy, stuffed with sweetened green mung beans and baked rather than boiled.

In Sta. Cruz, Laguna, the mochi is sprinkled with ground peanuts and sugar.

Masi is the Visayan version of mochi, wherein the rice balls are stuffed with ground peanuts and brown sugar or Muscovado. Found in many parts of Cebu and Leyte, it is also made with mashed gabi, or taro.

Tamales

One of the indelible imprints left by Mexico during the 250 years of the Manila-Acapulco galleon trade (1565-1815) is the tamales. Hereabouts, it’s always called in the plural, though it is also referred to by other names.

The Philippine version is made with ground rice cooked with chicken broth and coconut milk, and wrapped in banana leaves, and the filling may vary from region to region. It also has a sweet version, skipping the chicken broth and meat topping.

Though considered a special-occasion snack coming out only during town fiestas and Christmas season, it is now available year-round in places where it traditionally has been part of their culinary heritage.

Meanwhile, in Obando, Bulacan; Taal, Batangas, and some parts of Quezon province, their tamales are on the sweet side. Pyramid-shaped and approximately two inches square at the base, it is made of coarsely ground glutinous rice, coconut milk and sugar, topped with a wedge of salted duck egg and toasted grated coconut, with a hint of pepper.

In Cavite City, Robinson’s pyramid-shaped special tamales have more orange peanut sauce than the rice pudding. It is savory, peppery, nutty, and a viand in itself, with thin slices of chicken and pork adobo sa atsuete, and wedges of hardboiled egg, eaten as a spread over bread or as a viand with rice.

Called tamalus in Waray, the Samareños version has mostly the cloyingly rich peanut sauce with a fatty chunk of pork adobo or humba. Just like Cavite’s tamales, it is meant to be eaten with rice in a meal.

Down south in Zamboanga City, what makes their savory tamal unique is it is stuffed with sautéed sotanghon with chicken. It is mildly sweet, salty, and peppery.

Bibingka

Bibingkang kanin (Tagalog) and bibingkang nasi (Pampango) refer to the whole-grain glutinous white rice cake baked in a pan lined with banana leaf then topped with a thick caramelized coconut jam called minatamis na gata or kalamay hati (not to be confused with the Ilonggo kalamay hati to mean another kind of smooth, gooey ground glutinous rice cake placed in half a coconut shell, hence the name hati or half; see kalamay).

This same freeform biko is called sinukmani (left photo) in Laguna and Batangas. Its brown color is due to the addition of brown rice and brown sugar.

In Sta. Rosa, Laguna, a favorite afternoon merienda is the pairing of the sinukmani with the somewhat sour kilawin puso ng saging, a sweet- sour-salty balancing act. Meanwhile, down south in Cebu, Davao and other Cebuano-speaking parts of Mindanao, popular breakfast fare is puto maya (and center right photos) and a hot cup of local chocolate. A slice of ripe mango completes the trinity when in season.

Another type of bibingkang kanin or whole-grain glutinous rice is the biko. Instead of being topped with coconut jam, latik (Tagalog, Pampango, Ilonggo and Ilocano) or coconut milk curd is liberally sprinkled on top.

The Tagalog biko is brown in color with the use of brown sugar, while the Pampango version is yellowish with the addition of boiled, mashed squash. Not to add further confusion to this festive mix of sweet delicacies, the same term coconut milk curd latik means coconut jam in Cebuano and Boholano, santan in Bicolano, and laro in Ilocano (Tagalog minatamis na gata).

This fiesta rice dish bringhé/ beringhé is made of glutinous rice cooked with chicken and its broth, chorizo or red hotdog, coconut milk, seasoned with patis (fish sauce) and turmeric, and then topped with hardboiled egg, pimientos and raisins.

Of all the countless varieties of kakanin, bringhé perhaps qualifies as the only savory rice cake there is. In fact, the native Aetas of Pampanga and Zambales call it kalame manuk, or chicken rice cake.

It traditionally appears during fiestas in Pampanga, Bulacan, Cavite and Laguna. It is also a popular rice dish in Iloilo, called by the name Valenciana. So popular, in fact, it is served year-round in most eateries surrounding any Iloilo market.

The Arayat, Pampanga, version is served upside down, exposing its most sought-after tutong or the lightly burnt crusty bottom part (socarrat to the Spanish paella).

Bibingka refers to the oven-baked yellowish fluffy pancake made with galapong or ground glutinous rice, coconut milk, egg and white sugar. Traditionally, it was sold during the cooler months of September to December, ushering in the Christmas season. Although it is now available year-round, it is usually served with grated fresh coconut after a generous spread of margarine.

Special versions have slices of salted duck egg, kesong puti or carabao’s milk cheese, and/or ham.

The outdoor, ingenious oven used is a clay pot and metal sheet contraption, and is heated at the top and bottom with live charcoal. The same term is used in Ilocano, Pangasinense, Pampango, Tagalog and Bicolano.

Called bingka in Ilonggo, bibingka in Cebuano and Waray, this Visayan baked rice cake has coconut meat strips, no egg, tuba (coconut toddy) mixed into the ground white glutinous rice batter, resulting in a chewy and heavy rice cake. In the photo is a bingka maker found in the Huwebesesan (Thursday) market in Jaro, Iloilo City, using an improvised wood-fired oven made out of an empty cooking oil can.

Royal bibingka is a popular baked glutinous rice cake in the Ilocos region. It is slathered with margarine or butter, sprinkled with grated cheese and sugar.

Suman

Suman generally refers to rice cakes wrapped in various types of leaves like banana, coconut, buri or palm, and hagikhik (marantaceae phrynium). Whole-grain glutinous rice, ground or flour can be used, and variably flavored with coconut milk, coconut meat, sugar, salt, peanuts, chocolate, etc.

Above are the more popular suman in Pampanga and Bulacan: cigar-shaped suman tili (whole grain glutinous rice, sweet, soft texture, oil from latik); suman bulagta (to fall flat); coil-like wrapped suman ebos after the palm leaf ebos; ibos in Tagalog).

Wrapped in a triangular banana leaf, patupat of the Ilocanos is savory, somewhat salty and peppery in taste. Its sweet version is called linapet. The rectangular coconut leaf woven pouches impaltao, on the other hand, is cloyingly sweet.

It is boiled in a cauldron of bennal, or newly pressed sugarcane juice until it becomes syrupy. This is considered a rare treat since it is made only during sugarcane harvest. This same sweet impaltao is called patupat in Paniqui,Tarlac, as well as in the northern provinces of Pangasinan, Cagayan and Aurora. Confusing, indeed.

Tupig (Ilocano), intemtem (Pangasinense) is a grilled suman where the somewhat charred outer leaf wrapping gives a burnt, bitter taste to this rice-cake log. A thick batter is made out of ground pre-soaked glutinous rice, or glutinous rice flour, mixed with coconut milk, coconut meat strips, and sugar (white or brown).

It is then poured into an oiled banana leaf sheet, rolled and then folded on both ends. It is then grilled over live charcoal, or a hot skillet. A measure of a good tupig is crisp edges while remaining moist and chewy inside.

Suman bulagtâ, a.k.a. suman sa lihiya (lye), suman kambal (twins), suman magkayakap (embraced), magkatambal (pair, partner) in Batangas are always cooked in pairs tied together. Whole-grain glutinous rice is used, unflavored, brownish green and firm when cooked. Usually eaten with latik or freshly grated coconut meat, and sprinkled with sugar.

Up north in the Banaue rice terraces area in the Ifugao highlands, the heirloom red glutinous rice chayah-ot is the popular choice to make inat-tah suman. Often eaten as a snack with a hot cup of black Benguet coffee — make that black.

Morón is a specialty of Leyte and Eastern Samar using glutinous rice flour to make a delicious, two-in-one suman. A white, elastic kalamay is made with coconut milk, while another is flavored with chocolate.

Two long strips of each are intertwined and then rolled within a banana leaf sheet and tied on both ends. It is then steamed, fusing the two strips to produce a somewhat streaky-looking little log. It is also called bakintol in Waray, the language of Samar.

Suman maruecos/ marwekos is a popular rice roll in Isabela and Bulacan, made out of ground purple glutinous rice and topped with latik (coconut milk curds) before it is rolled in banana leaf. It is usually served with a thick sweetened coconut cream.

Budbod is the Cebuano/ Boholano term for leaf-wrapped suman. It is quite popular in the painitan or coffee shops in marketplaces in the Visayas, where it is eaten for breakfast or merienda with a hot cup of coffee or chocolate.

Variably flavored with sugar, chocolate or sometimes peanuts, budbod’s most famous variant is the one made with millet budbod kabog. It has a buttery, smoother texture than the glutinous rice rolls, quite popular in Dumaguete and the southern Cebu towns of Catmon and Sogod. It’s so good I could gobble down a dozen in a jiffy.

Binut-ong

Binut-ong is glutinous rice cooked with coconut milk wrapped in banana leaves or hagikhik leaves (marantaceae phrynium) where available. It is sold ubiquitously as street food to go in marketplaces, much like the Cebuano pusó or heart-shaped boiled rice. It is generally found in all six provinces of the Bicol region, but more popularly in the mainland provinces of Camarines Sur, Albay and Sorsogon.

It is eaten usually for breakfast, with a sprinkling of sugar together with a hot cup of coffee or chocolate. An elaborate serving (photo above) is with hot, thick chocolate espresso, scrambled egg and dried salted fish. Its texture is not firm like suman, but rather creamy and risotto-like.

Mamis

Mamis is the collective name for sweet delicacies made by the Maranaos of Lanao Province in Mindanao. In the painting above, a common sight in the marketplace is this mamis vendor with an array of sweet offerings.

Hanging from top left are dodol/ dudul (leaf- wrapped whole grain glutinous violet rice sweetened with Muscovado); yellow cylindrical ones are tiyatug/ tiyateg or sweetened rice noodles; while the disk mounds are amik, a non-leavened rice pancake (painting by Claude Tayag).

Tiyatug

The tiyatug/tiyateg or sweetened rice noodles is made with a watery rice batter with coconut milk, egg and sugar, placed in a perforated bowl-like coconut shell strainer, and then dripped through a pan with piping-hot oil. The coco strainer (Maranao sarà na lagás; Maguindanaon pangulayong; Cebuano tagaktakan) is tied from above and swayed in a circular motion to form a net-like fritter. It is then folded or rolled into different shapes.

This same tiyatug is called ja by the Ta’u-sug, tinagtag by the Maguindanaon, lukot-lukot in Chavacano (Zamboanga City), and amik to the Kalagan/Kagan of Davao del Sur. (Sources: Chef Datu Shariff Pendatun and Edgie Polistico, author of Philippine Food, Cooking & Dining Dictionary).

Mamis

Sometime in 2005, while traveling around Mindanao, my group was treated to a hosted pagana at the Mindanao State University in Marawi City. Pagana is a traditional feast of the Maranaos and Maguindanaons, where guests are given a place of honor separate from the hosts.

It was like dining in a full technicolor set, seated on cushions on a dazzling, intricately woven mat-covered floor and overhead appliqued cloth covering.

Spread on the large brass plate covered with another bright red appliqued cloth that served as a low table were Maranao staples, starting with kuning or turmeric rice, bakas or smoked whole tuna, badak or green jackfruit cooked with palapa, a tilapia dish and cara-beef rendang (stew). Served together with the savory dishes were tiyatug, browa (similar to mamon or sponge cake), dodol, lukatis or sugarcoated pretzels, and other sweet delicacies.

These mamis were served as part of the meal, not as desserts or meal-enders (painting by Claude Tayag).

Carioca

Carioca/karyoka are the fried rice balls coated with caramelized sugar. A popular street food, they are sold in many parts of the country. It’s called tinurok in Pangasinense, tinudok in Ilocano, and duro-duro in Novo Ecijano.

Pilipit Boscaron

Pilipit boscaron is like a fried doughnut in the shape of a pretzel. Well, close to it. But that’s where the similarities end. It is made from a batter of rice flour and mashed boiled squash, deep fried and then coated with caramelized sugar, giving it a crusty, crisp outer layer, yet chewy and airy light inside.

The ones I tried in Lucban, Quezon, were from an ambulant vendor from Tayabas, which had the consistency of Spanish churros, crunchy yet fluffy and light, considering they were made much earlier in the day.

Not particularly having a sweet tooth, I gobbled six down one after another. It could give foreign donut brands a run for their money. That alone made our trip worth it, and I wouldn’t mind driving back there for another bite. Make that a dozen bites, and more to bring home.

Maruya

Maruyang saging is the fried saba (plantain) banana fritter, made with a batter of rice flour and egg. Called maruya in Tagalog and Pampango, baduya in Waray, pinaypay (fan-like) in Cebuano, sinapot in Bicolano and Waray, jualan in Ta’u-sug, the ripe plantain is sliced in a fan-like fashion, much like when one spreads out one’s fingers, with each finger still attached at the base. It is then dipped in batter and then fried until golden brown. White sugar is sprinkled over it. (Source: Edgie Polistico, Philippine Food, Cooking & Dining Dictionary).

Okoy

Closer to home, the orange- colored okoy in my hometown of Angeles City is also made with grated green papaya and topped with shrimps. The somewhat bulging, saucer-size fritter has a thick, heavy batter, making it a hard shell to bite into.

Kalamay

Kalamay/ calamay is the rice cake made with glutinous rice flour, coconut milk, sweetened with brown sugar or molasses, and can be flavored with squash or ube. It is the base for other kakanin like sapin-sapin, sundot kulangot, and morón. The same term is used in Tagalog, Cebuano, Boholano and Waray, kalame in Pampango, and kalamay hati in Ilonggo and Negrense.

Sapin-sapin

Sapin-sapin is the Tagalog, Pampango and Novo Vizcayno term (pituklip in Ilocano) for the colorful, multi-layered viscous rice cake often topped with latik or coconut milk curds.

Each color is supposed to taste differently, i.e. violet for ube, yellow for squash, white for coconut milk. But the fact is, each layer has the same taste as the others, artificially colored to make it look festively attractive.

Celebrate “Kakanin Day” on June 11 with the Dama ko Lahi ko Instagram account.