9-year-old boy writes letter to Duterte. Experts weigh in on the president’s language

When Skye submitted his assignment for one of his classes a few weeks ago he had no idea it would go viral and reignite an old conversation.

The homework was to pen a letter to the president, the one currently occupying Malacañang. Here’s what the Grade 3 student wrote.

Dear President Duterte,

At home, we are told to respect one another. There are words that we are not allowed to say. Sometimes I hear you on television. I am shocked at how you curse and bad mouth others.

As president, don’t you think you should be a role model for good manners and right conduct? I hope that you will change your attitude. Then maybe I will respect you more.

Thank you.

Sincerely yours,

Skye

A photograph of the handwritten letter by the 9-year-old boy was posted on the Twitter page of The Baguio Chronicle, a weekly newspaper based in Bagiuo where Skye resides. The caption includes this statement from the child’s mother, who apparently sent it to the publication: “Our children are also aware of how a good leader should lead a country.”

A child from Baguio writes President Duterte a letter.

— The Baguio Chronicle (@baguiochronicle) April 13, 2021

Skye’s mother had this to say:

“As a requirement in my son’s school, he was asked to write a letter to our dear President. Here’s his letter to him. Our children are also aware of how a good leader should lead a country.” pic.twitter.com/m0nx817T87

The post quickly gained traction online. To date it has received over 38,000 likes and retweets and hundreds of comments. The letter also went viral on Facebook through individual posts and group chats.

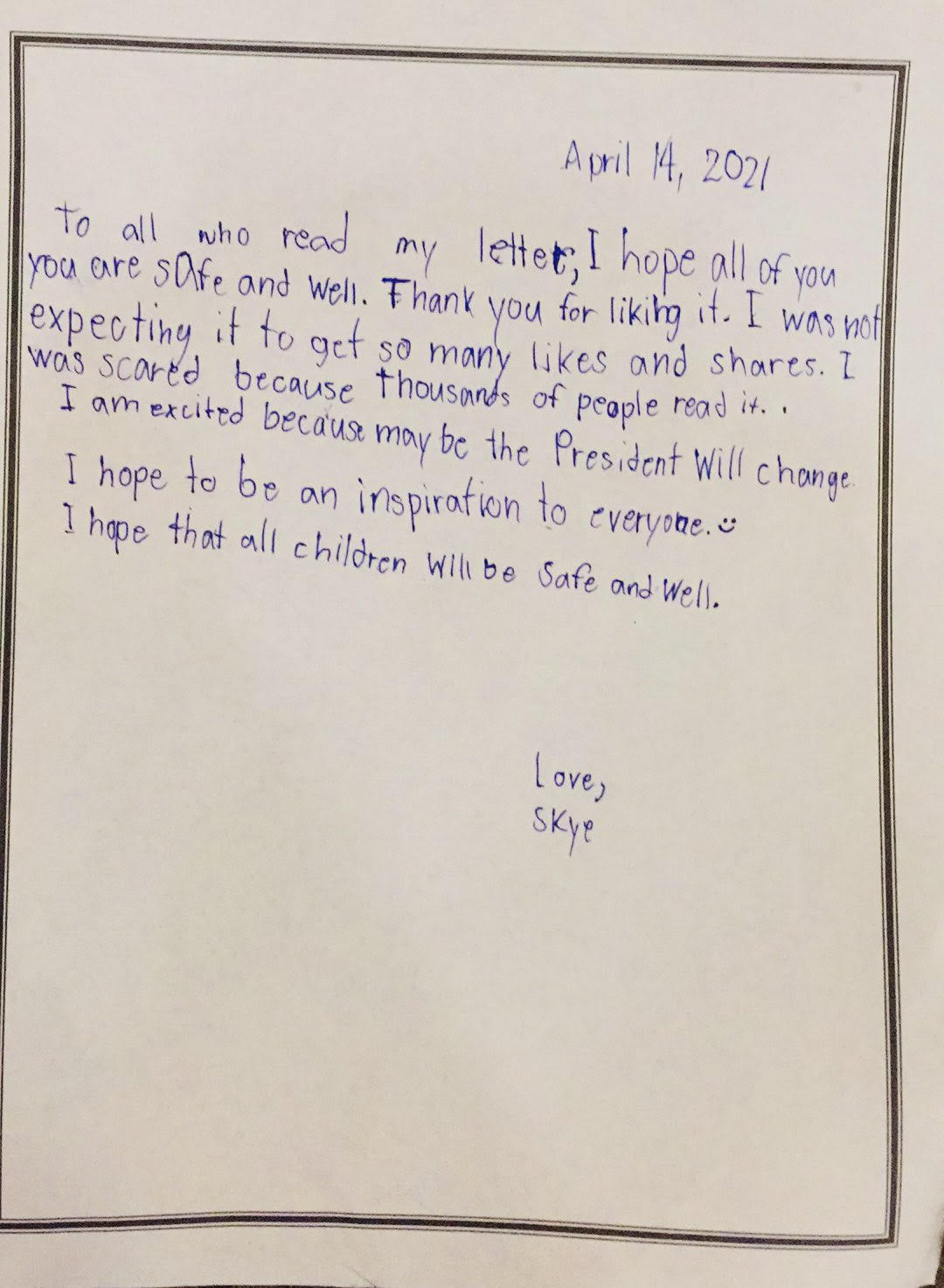

In fact, the response was so huge it prompted Skye to write a Thank You note, also handwritten, for those who expressed admiration and support. It was also released in The Bagiuo Chronicle the very next day.

Not all feedback was positive

As with every criticism leveled at the president, Skye’s callout was met with derision, disdain, and discrediting by many vocal Duterte supporters.

They weren’t as brutal, though, as they normally are when responding to adult critics. The language, in fact, was muted, which is ironic given the situation. And the attack was mostly directed to Skye’s parents, scoring them for being lax, even neglectful by letting their child listen to the president, chastising them for teaching the kid to be disrespectful to the highest official in the country, saying that they are only using him to advance their political agenda, among other things.

It’s certainly nowhere near the vitriol they unleashed on former Senator Antonio Trillanes in 2016 for the anti-Duterte video that they alleged he produced, the one showing a succession of children firmly talking about character traits and behavior they believe are not suitable for public office—among them cursing the Pope and making sexist remarks against women—interspersed with actual footage of then-mayor Duterte doing the exact deeds during his public presidential campaign sorties.

An adult who says bad words, shows lack of respect, curses them, puts them down—this is so potent. Children and adults absorb this whether they like it or not.

The difference between the video and Skye’s letter? The former is for reel and features child actors spewing scripted dialogue. Skye and his letter, taken at face value, are for real. But regardless, this new missive has pushed the issue of the impact of foul adult language and bad behavior on children back into the public conversation.

The expert view

It’s a discourse that clinical child psychologist and national social scientist Honey Carandang, PhD, knows all too well. She has been on the receiving end of the ire of the president’s rabid supporters for sharing her unflattering expert opinion on the impact on children of the president’s habit of talking about killing people when he speaks about the war on drugs.

“I was bashed in the most vicious terms,” the author of the book Self-worth and the Filipino Children recalls during the interview for this piece. “They [the bashers] are the most creative people in terms of coming up with bad words to insult you.”

This episode happened early on in the president’s term. Despite the experience, Carandang has not backtracked, much less silenced. “It’s definitely wrong for children to think that killing is normal,” she reiterates. “That is a no-no. When they hear it all the time and nobody says it’s wrong because the one talking is in a position of authority that everybody should respect, the children absorb it.”

And it’s not just the talk of violence. Carandang says that the constant lying, cursing, and “making mura” on television are highly eroding the “dignity of people” young and old alike.

“An adult who occupies the highest position in the land and says bad words, shows lack of respect, actually disrespects people, curses them, puts them down—this is so potent. Children and adults absorb this whether they like it or not.”

When told about Skye’s letter, Carandang sounded surprised, like it was her first time to hear about an actual child addressing the president in no uncertain terms. She describes Skye, based solely on his letter, as a thinking, wise, and discerning child for not absorbing the president’s language and behavior the usual way and for knowing that it’s wrong. She also praises the young boy for his bravery and courage to speak up.

You cannot just teach what you say. You need to model what you are teaching. When children see the inconsistency, they will have extreme confusion.

“What a hero,” she declares. “We must make him feel proud of what he has done. He must not be bashed at all.”

It’s called validation. Carandang says it’s very important that children like Skye be acknowledged and recognized every time they do something good and brave. “It would be very difficult for them to sustain it if there are no significant adults who will make them feel that what they’re doing is good and right.”

It doesn’t have to be the entire village. It doesn’t even have to be the whole family. One significant adult would suffice so long as he or she believes and validates the child all the way.

Predisposition for imitation

Aside from validation, another crucial tool in teaching children is modeling. “You have to teach what you do,” notes Ateneo de Manila assistant professor Boboy Alianan, PhD, of the university’s Department of Psychology. “You cannot just teach what you say. You need to model what you are teaching. This is extremely important. When children see the inconsistency between what you say they should do and what you are actually doing, they will have extreme confusion.”

Apparently Skye’s parents are doing a good job at modeling. His letter shows that he has a firm, unshakeable grasp of what’s good and bad, right and wrong. Instead of having doubts on the unassailability of his parents and their teachings in the face of the opposite examples that the president routinely unleashes, he tells the public leader off, quite firmly at that.

This points to people’s predisposition for imitation. Alianan says that we don’t necessarily copy or emulate everyone we see or hear, but typically only those in authority directly over us. For children like Skye, it’s the parents who hold that position of power in the home setting. Any outside figure or force that goes inside the space will be evaluated and measured against the standards and rules that have been set by the parents.

And the more the parents model these themselves, the stickier they become on the children. Anything that runs counter will be seen as an incongruence, even a violation.

“In my home where I’m watching TV, I’m taught by my parents I should not speak these words,” Alianan explains. “This is disrespectful. My parents don’t say these words. Why is this man, who is supposed to be the leader of the land, saying this? There is then a violation of this rule in my own home.”

But how can parents with children who don’t have Skye’s wisdom and advanced sense of self respond when the kids get confused and start asking questions?

Alianan offers two scenarios. “They can tell the child the reality that this president is extremely popular. Additionally they can tell them whether or not they like him. And they can justify their position, especially if they like him. But those who have an opposite opinion can say that he’s very popular and it’s a sad thing because many people are used to this kind of language and they think there’s nothing wrong with it. But I’m teaching you and I’m also modeling to you that this is wrong.“

Filipinos divided by two views

Skye’s letter also touches on another major issue. “I hope that you will change your attitude,” he writes at the end of his message. “Then maybe I will respect you more.”

Respect and filial piety, Alianan says, are extremely important in Asian countries. “The respect for authority. In our language there is po and opo. This is embedded in our culture and it’s how we teach our children and even adults.”

Filipinos, he says, are divided by two views. There are those who believe that anyone can freely criticize authority figures for doing what might not be right. And then there are those whose idea of respect for authority is all-encompassing, “that the authority figure is irreproachable, can not be corrected.”

He notes that the second one seems to be more pervasive. And it’s not just in the public sphere. “This happens in many of our homes,” he states. “Basta. Ako ang nanay mo. Sumunod ka na lang. Wala nang tanong tanong. Irreproachable. Obeyed to the letter.”

Skye’s letter clearly shows where he and his family stand on this contentious divide.