The lost arts before Zoom and Viber

The fleeting mementos of a forgotten age — photographs and poems, letters and sketches — are always objects of fascination at any auction. Reading the private messages of famous people is always irresistible, offering the same kind of guilty pleasure as glancing furtively through your boyfriend’s directory. One muses for similar reasons about identities and significances. (“Who in heavens is CRT and why do they text so late at night?” is one thought balloon.)

There are also arts lost because of the comings and goings of technology. Reading has been pushed aside by TV, poetry by Netflix; but there is still something riveting about discovering lines handwritten by an icon such as Jose Garcia Villa. A National Artist for Literature, he was, truth be told, more famous abroad. He invented the “comma poem” which caused a sensation in New York City and there is an example of it at the León Exchange online auction, edition XVI. It’s wonderful to reminisce about a bygone age when Filipinos walked the earth as giants. In Garcia Villa’s case, he is counted among America’s literary greats such as Tennessee Williams, W.H. Auden and the young Gore Vidal.

Two wonderful souvenirs of that time consist of one such “comma poem,” numbered 158, from his “Doveglion” collection.

A, living, giant, all, in little pieces,

Out, of, death’s, kingdom, into, shine__

It’s signed, of course, “Jose, Garcia, Villa” and dedicated to Armando D. Manalo, journalist, diplomat and an adviser to the United Nations in New York.

Accompanying it is what appears to be a heretofore unknown poem by Garcia Villa, written out and signed in his own hand. A second lot features a drawing of a mythical man with three eyes and is also signed.

Postcards, on the other hand, are really nothing but ready-made pretty pictures. They became popular because the first cameras were rare and expensive. As multiple lenses now come attached to our phones, the postcard itself has been replaced by Instagram.

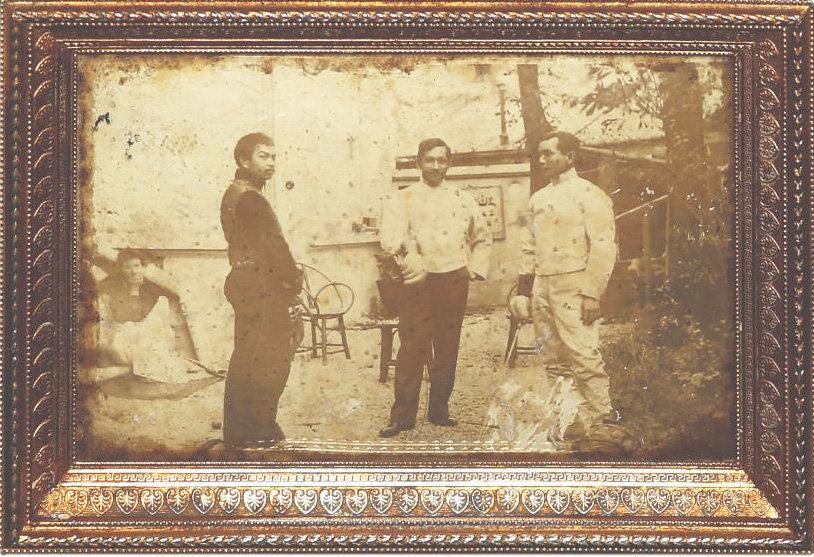

(Speaking of photographs, there is a print on the block from the collection of the eminent collector Don Alfonso Ongpin of Juan Luna, Jose Rizal and their buddy Valentin Ventura, in between fencing matches outside Luna’s Paris apartment. The French (who never forget) have ensured that the apartment’s patio where the photo was taken still looks pretty much the same according to Google Earth.)

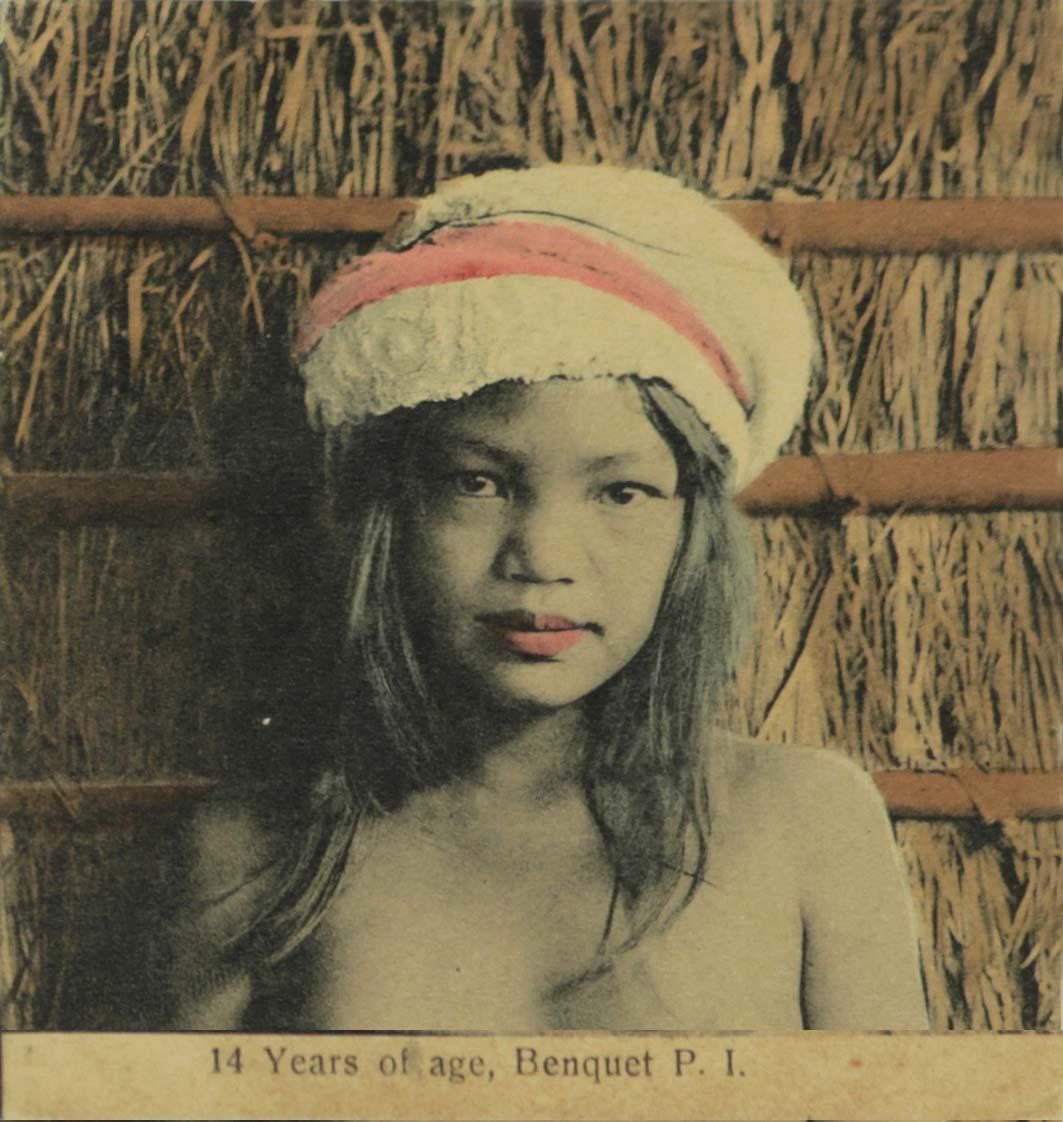

“Private mailing cards,” as a result, are now increasingly rare. Various sets from the first years of the American regime capture the vistas of its first colony, from the mountains of Benguet, the rivers of Luzon, and the houses of Manila — as well as its conquering generals and armies.

There is also a couple of postcards from another National Artist, Fernando Amorsolo. One can’t help staring at his early signature that is now attached to multimillion-peso paintings and examining the mysterious greetings. Dated in the early 1900s, the cards are Baguio scenes — one of which looks like Kennon Road and another of “14 Years of Age — Benguet — P.I. (Philippine Islands).”

Not one to let go of the idea of secret communications, there’s also a cartoon by Amorsolo of “The Inattentive Student” for the magazine Telembang, a comic strip from the 1920s. In this day and age, the pupils would be sending disappearing messages on Snapchat instead.

Other postcards detail the works of Jorge Pineda, who was Amorsolo’s mentor.

There are also flash cards that feature Jose Rizal’s last poem, the “Ultima Adios” which was written and smuggled out before his execution. (These recall a time when patriotism was revered and it was the custom to recite the “Ultimo Adios” at dinner parties as part of the entertainment.)

Thanks to the quarantine and COVID-19, we are also running out of things that used to define us (least of which is remembering to dress up the bottom halves not seen by Zoom). In case you ever forget what that means, there is a spectacular dressing table with a full-length mirror wreathed in a baroque frame. This was taken from a mansion on Calle San Rafael near Malacañang from a time when appearances truly mattered.

Some things, however, should be forgotten sooner than later. The fancy men’s clothiers, Brooks Brothers, may have filed for bankruptcy but my condominium has newly imposed the nonsensical rule that repairmen may only set foot on the premises “dressed in long-sleeved shirts” to better prevent the transmission of the virus.

Unfortunately, the age of “requisitos" — the Spanish term for permits, licenses and forms in triplicate — appears to have been resurrected by various martinets just for the lockdown. Detailed “health declarations” are needed for the simplest thing, including getting a small latte at Starbucks. It’s time to remember that this colonial legacy for interminable paperwork, the passes, the contact-tracing would have fit right in with the Guardia Civil. A set of rare “papeles sellados” or documentary-tax papers from the 1800s demonstrate this penchant. Just a little warning: the cedula would eventually drive the Filipinos around the bend. We would eventually rise up in arms and tear them to shreds at Balintawak. Now, that may be something worth remembering.