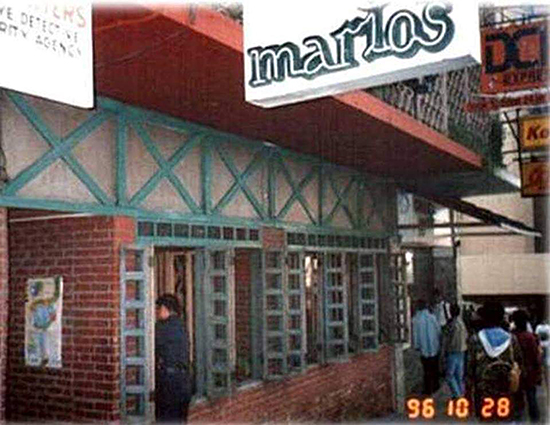

Mario’s and the lasting legacy that my parents built 50 years ago in Baguio through grit, grace, and a little luck

Where was I on Sept. 1, 1971, the day Mario’s in Baguio opened? This question has boggled my mind for a number of years.

My parents Mario and Nenuca took that leap of faith, fate and opportunity 50 years ago to put up a business of their own. My father was trained as a lawyer but was coerced, I believe, by my grandfather, a representative from Laguna since 1919, three years after he completed his law degree at Georgetown University.

Instead, my dad joined the corporate life, employed by San Miguel Brewery, then assigned as VP for Singer Sewing Machine in Northern Luzon. This is the reason our family landed in Baguio circa 1967.

My mother, on the other hand, was always the hardworking entrepreneur; she had a dress shop in our garage at their first home in 1958 at Bel Air Village, Makati.

The dignity of labor was something my father taught us at an early age when my mother made us work as busboys, dishwashers and cashiers on Friday and Saturday nights at the restaurant in Baguio in the early days.

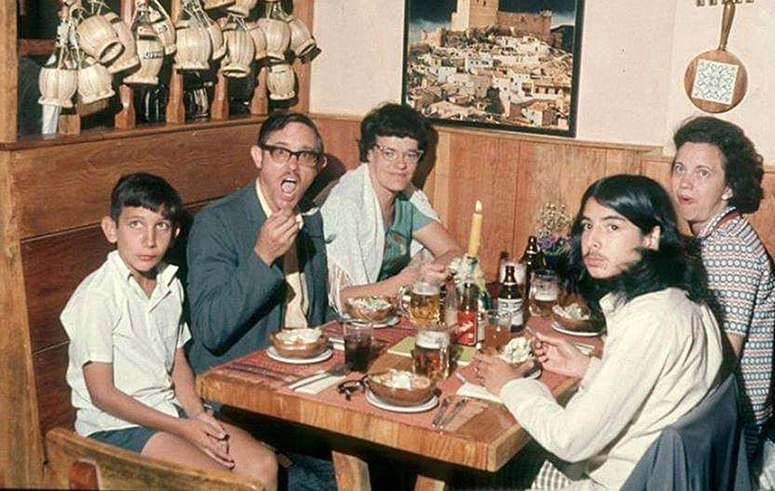

Both my parents loved to entertain and every weekend had dinners at home — my father being the ultimate host, with a gregarious personality, wit, and class that money can’t buy. My mother grew up “dining,” not eating; she read Etiquette by Amy Vanderbilt (a must-read), amid friends who only experienced fine-dining restaurants. Thus, we grew up having dinner in restaurants with no prices.

Mom’s recipes came from my grannies, one Española and the other a Tagalog from Pagsanjan — mestizo cuisine, much like Mario’s original menu would eventually become.

Friends back then would coax my parents: “Why not open a restaurant?” So that’s what they did. We had batchoy and kare-kare intertwined with callos and lengua plus simple pastas fettuccine and spaghetti with meatballs and pizza.

Our priciest dish was a steak ala pobre at P28 on our first menu in 1971. The only remnant of that menu is a photo; all our original memorabilia literally went up in smoke when the first restaurant on Session Road burned to the ground 20 some years ago.

Lessons learned in the college of life

Dignity of labor was something my father taught us at an early age when my mother made us work as busboys, dishwashers, and cashiers on Friday and Saturday nights at the restaurant in Baguio in the early days. All our friends from Manila would come up for the Holy Week and Christmas holidays and there we were, working and arriving at parties late.

Today, I’m very grateful for the work ethic we learned at a young age. Working, to me, is a passion and that’s what I tell our employees today: come in to work daily, not because they have bills to pay, but because they love and enjoy it. Working seven days a week comes easy for me, because I simply enjoy what I do.

Mom always had these Spanish clichés like, “El que tiene tienda, que la atienda” (He who has a store must attend to it), and in our line of business, it’s all about attention to the details. And that’s how my parents trained not only my siblings and me, but our employees in Baguio. They treated everyone who worked for them as their extended family. And the employees in turn would bring in their relatives to work for us.

They believed in remunerating them reasonably. For me and my siblings, wages were not like what most children of business owners earned, but were commensurate to rank-and-file employees. Like them, we hustled and earned from service charges and tips. We had to start from the bottom so the harder and longer we worked, the higher our salary grew.

This is a policy that I continued with my own business: if my children wanted to work for our donut business after college, they must first work in another related business to teach our employees and myself what they learned from that experience. We didn’t want them to become COO: “Child of Owner.”

Stroke of law

I’ve always believed in the philosophy of the Chinese — that in business, it isn’t all hard work but also an element of luck that brings success.

Exactly one year from our September 1971 opening, martial law was declared. A curfew was imposed immediately and later on, a travel ban declared. This meant people couldn’t spend their holidays in Hong Kong or San Francisco anymore. In those days, destinations like El Nido, Boracay or Subic didn’t exist.

The reason Baguio was called the Summer Capital of the Philippines was because of the oppressive heat in Manila — so overbearing for American officials at the time that Gov. Gen. Taft had Kennon Road built in Baguio, where the weather was cool and relaxing, as it continues to be today. And since those days, Manila’s 400 have built their own Baguio summer homes surrounding the Baguio Country Club to spend their holidays there.

That Christmas season in 1971, Mario’s on Session Road was packed to the rafters for lunch and dinner every day; I remember never working so hard in my life. And again when Holy Week came in March, the same thing happened.

By 1973, we had become so popular that my parents decided to open our second branch on Makati Avenue, then the restaurant row of Manila. Makes me wonder sometimes: if President Marcos had not declared martial law, would we have become popular so quickly?

‘Coño’

That Spanish expletive is, I believe, the equivalent of the Pinoy “putangina.” If I recall right, that is what my father told one of his good friends one night while having cocktails at the Officers Club in Camp John Hay sometime before they put up Mario’s. I heard him say it in frustration when his friend asked him where they should have dinner that night and he said, “Coño, the only restaurants in town serve Chinese food.”

It was true: the popular restaurants in those days were Rice Bowl, Star Café and Dainty’s on Session Road. The other restaurants serving western cuisine were the Baguio Country Club but one had to be a member. Then there was the Main Dining Room of the Officers Club and Nineteenth Tee at the US Air Force base at Camp John Hay, but one needed a special pass to enter the base.

Another was Forest House owned by these two Spanish matrons, Mrs. Rupp and Mrs. Larrocea, but one had to call days in advance and only one group at a time could dine in their home. So that “coño” from my dad was a call to seize the opportunity and fill a need. And so the idea and concept of Mario’s was born: a restaurant where you could eat anything — other than Chinese food.

Romance in the City of Pines and Mario’s

Ever since I can remember, Mario’s in Baguio always had a string of regulars from the film industry and other VIPs up for rest and recreation.

One of my first starstruck moments was when Dolphy would come to dine at our restaurant, always accompanied by an equally famous and beautiful companion in the ’70s. I vividly remember reserving our Table 7 at the back of the dining room, away from the glare, for Lotis Key, the beauteous Amerasian movie star. The stars would come regularly, usually on weekdays when there were fewer visitors in town. Eventually, in another time or year, he would be with Pilar Pilapil, equally beautiful. Dolphy’s taste for beautiful women was legendary.

One of our captain waiters, Nestor, recalled to me recently how Gabby Concepcion and Sharon Cuneta would always dine at Mario’s whenever they visited Baguio. Same with Eddie Garcia, Vilma Santos, Nora Aunor and Nida Blanca.

There were many film industry regulars, as well as political bigwigs like Chavit Singson, whose family had just taken over from the Crisologos as the political dynasty reigning supreme in Ilocos Sur. That’s about the time he and I struck up a casual friendship that continues to this day — all because of a girlfriend I had.

The Mario’s Way and the admiral of the US seventh fleet

My parents loved to tell this story. One weekend evening, our restaurant was full and a reservation had been made for the admiral of the US Seventh Fleet based out of Subic Bay. It was a large group hosted by the admiral for a slew of officers.

When my parents approached the US admiral, as they always did to ask customers how their meal was, the guest immediately complimented our staff on the impeccable service and how delicious their meal was. And he added that our restrooms were the cleanest he had experienced in all of Southeast Asia.

That tickled my parents; I remember my mother replying, “You can imagine how clean our kitchen is.” This story is how my father coined the phrase “The Mario’s Way,” which today is the epitome of what the Mario’s experience is all about.

To answer the question of where I was 50 years ago in 1971, I was in Manila, a freshman taking up my Liberal Arts and Commerce degree at De La Salle College. Must have missed a grand party that day in Baguio, never imagining that, five decades later, the legacy my parents began would continue today.

At all our general meetings, where all our employees from managers to busboys are present, that catchphrase captures the standards they should uphold. It simply means impeccable service; tasty consistent food in well-appointed dining rooms, with the cleanest kitchens (and restrooms) in town. That is the way our standards are measured to this day.

Mario’s: The next level

This year marks a milestone celebrating the 50th anniversary of Mario’s in Baguio. November also marks the 40th year of our branch in Quezon City along Tomas Morato Avenue. Our second restaurant after Baguio was on Makati Avenue which, after two decades, moved to Greenbelt at Ayala Center. Then came Mario’s Ortigas in 1990, but only after my parents brought our brand to California, opening as Calesa Restaurant in 1986. We also had Beverly Hills Deli in Greenbelt.

But today, only Baguio and Morato remain as, somewhere along the way, after I left the family business to open my own donut franchise up north for 17 years, a sibling ended up closing all our restaurants but two.

My endeavor to go at it alone in 1995 made me realize that, like my parents before me who pioneered fine dining in Baguio in 1971, I, too, wanted the same with fast food, opening six months before a major hamburger brand did in Baguio. Like my parents, who had the vision and courage to go where others hesitated, my wife had to decide to leave Mario’s to go on our own way.

My only sister did the same; today, she runs a very successful restaurant that I feel complements our brand. The vision that I try to impart to my family and our employees is of transforming the Mario’s Group into a restaurant management group that will operate food brands, not necessarily called Mario’s, but including coffee shops, delis, fast food, and cloud kitchens (kitchens set up for online delivery/takeout only, in the shortest time possible).

Which now brings me to answer the question of where I was 50 years ago in 1971. I was in Manila, a freshman taking up my Liberal Arts and Commerce degree at De La Salle College. Must have missed a grand party that day in Baguio, never imagining that, five decades later, the legacy my parents began would continue today. I miss them, and dedicate this story in their memory.