The internet is a space for the lonely

In the 1998 anime Serial Experiments Lain, Lain Iwakura is a socially withdrawn 14-year-old girl who becomes obsessed with “The Wired”— essentially a fictional version of the internet,

“The Wired” is a sea of the collective consciousness and unconscious where information pervades, desires permeate, and connections are made. It is also where Lain finds respite from her loneliness, where the desire to connect is miraculously fulfilled, spanning great distances in space and time.

‘KAKAKOMPYUTER MO YAN’ and conditions of possibility

That the internet is a space for the lonely, the broken, the forgotten, the silenced, and the unheard similarly permeates in “KAKAKOMPYUTER MO YAN,” an anthology of internet art curated by Chia Amisola. As the curator notes, historically foundational to the project is Onel de Guzman’s creation of the ILOVEYOU Virus in the year 2000, which the anthology pays homage to in a glittery digital shrine by Mac Andre Arboleda that links news documentations of De Guzman’s globally disruptive “Love Bug”—a malicious “love letter” email attachment that steals Wi-Fi passwords to provide internet access for those without.

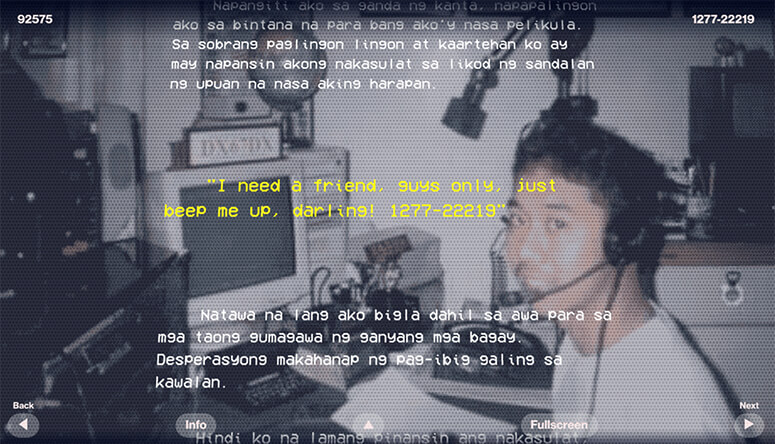

In an adjacent commemorative work from the anthology, online persona Deepweb

Dumaguete retells what has now become a piece of digital urban lore in Filipino internet culture: “1277-22219” is the story of Kuya Marlon, a lonesome telecommunications worker who falls in love with a beeper operator named Elise, only to one day find his affections unrequited and his calls forever unreturned.

The stories of Onel de Guzman and Kuya Marlon both speak of a desire to connect. The creation of the “Love Bug” draws from a desire that is deeply socioeconomic, a third-world lack that becomes manifest in the way we access and experience the digital world—or rather, the limited access to and experience of it, apparent in the practice of tingi-tingi via “pisonet” shops and the resort to spaces of back-end illegality and piracy. “1277-22219,” meanwhile, speaks of a desire that is psychosocial and interpersonal.

While Kuya Marlon’s story, set in the year 1997, is loosely based on real experiences, it is a fictional work first circulated online in 2017, the truth of which has come to border the real and the fabricated. It has become a story of the folk, a story that somehow finds every Filipino internet user who, in this milieu of urban disenchantment, has ever found themselves disconnected or alienated, whether in real life or online.

The colloquialism “Kakakompyuter mo yan!” is an attempt to rationalize causally, while suggesting a skepticism towards new technologies (and the possibilities they bring) that draws from present anxieties. In response to such skepticism, the works in the anthology endeavor a stubborn exploration of these new technologies anyway, conceiving the overwhelming nature of the digital as conditions of possibility—as trajectories from which to imagine, out of our persisting anxieties born from lack and alienation, new possibilities and new connections instead.

Online, we increasingly see novel—or more aptly, unexpected—ways of making connections in the form of digital transformative works. Connections are often forged through hyper intertextuality—for example, in media such as memes, fan art, fan fiction, and fan-made edits or videos, which contain layers of media references building upon each other through a cycle of mimicry and remix to create a derivative or transformative work.

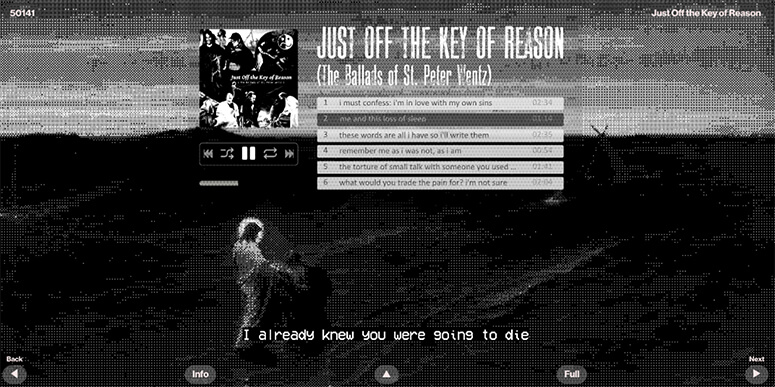

Elise Ofilada’s “Just Off the Key of Reason (The Ballads of St. Peter Wentz)” is one such work from the anthology, a web playlist of spoken poetry that weaves together the author’s experience of grief with Fall Out Boy lyricist Pete Wentz’s stubborn affinity for indulging in his own heartbreak, and St. Peter the Apostle’s imagined guilt and grief from the death of his beloved Jesus. Bits and pieces of Fall Out Boy’s lyrics are taken as titles for the playlist and its songs, which indulge the author’s grief in a manner that transcends their own to become St. Peter’s, to become Wentz’s—to become anyone else’s in a flight of intentionality and meaning—yet still comes back to itself.

The playlist is a confession indulging in one’s own loss, guilt, and grief, despite not really knowing if forgiveness awaits on the other side—or if there is even anyone listening, seeing, or reading these things we say, share, or write publicly online. It speaks of a desire to connect that is ultimately self-indulgent, but here—at the same time—the playlist is a form that prompts a song or text to become someone else’s.

Playlists are sometimes referred to as “mixes” because they compile or “mix together” songs selected from pre-existing collections. When the playlist’s curation weaves together new threads of intertextuality or constellates lines of flight between formerly closed texts (songs) it contains, the mix becomes a remix, opening possibilities for re-readings of these texts—in this case, the author, St. Peter, and Pete Wentz—such that their worlds poetically bleed and blur into and against one another.

Hyper-linking, world-making

This hyper-constellated-ness of the playlist as remix—a tendency exemplified in digital transformative works—presents us with a more relevant way of looking at art and contemporary visual culture situated in a pervasively “hyper-linked” world. It presents us with a way of looking that draws from the idea of digital worlds as ever unfolding, and the internet as an archive ever unfinished.

If the digital connections we make then tend to be transformative and plural, our

self-indulgent desire to connect online must be symptomatic of something much bigger than ourselves—perhaps, an ever-persistent desire for new worlds and possibilities.