It is a story that owes its provenance to a series of alleged Marian apparitions nearly six decades ago.

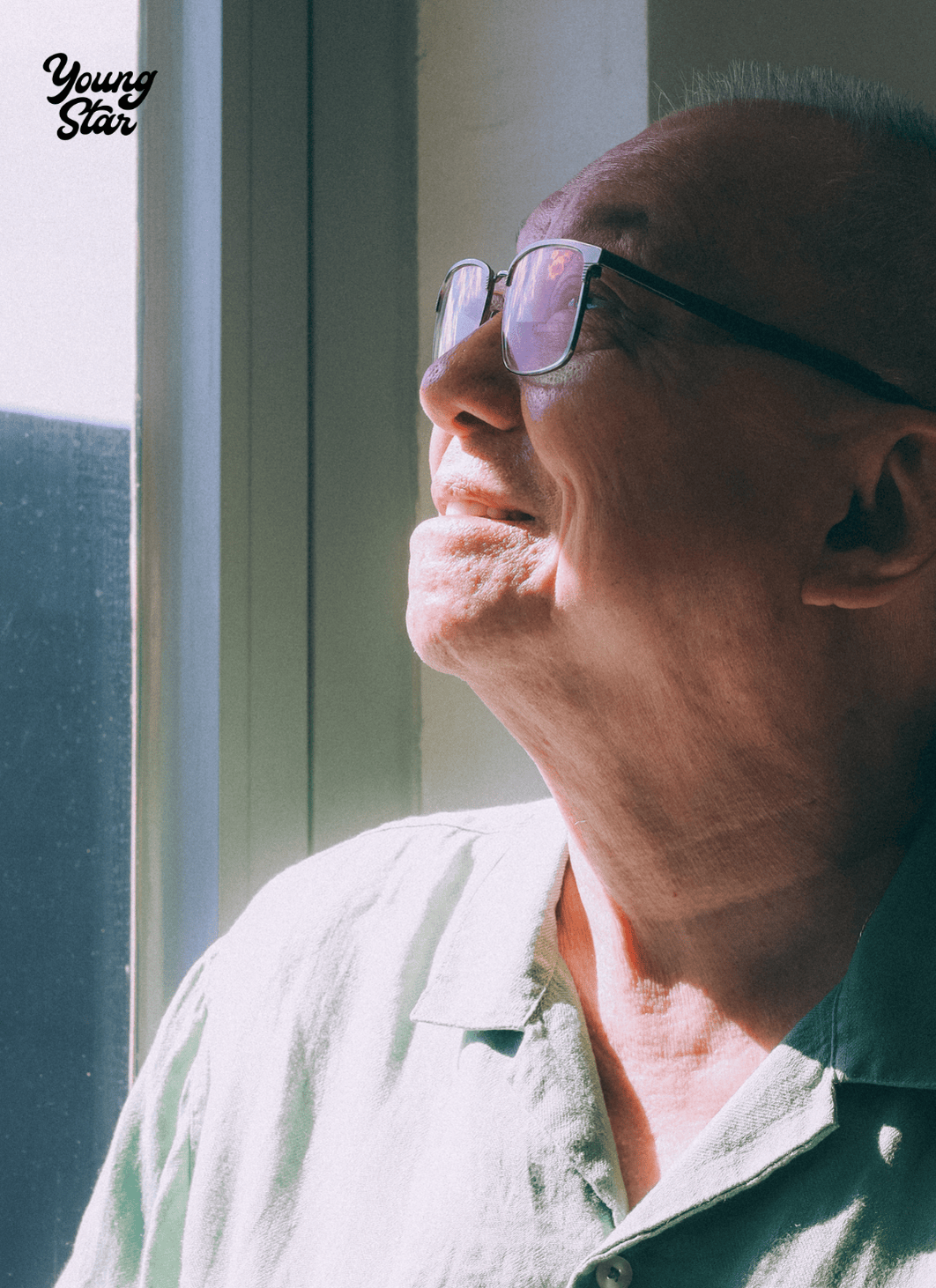

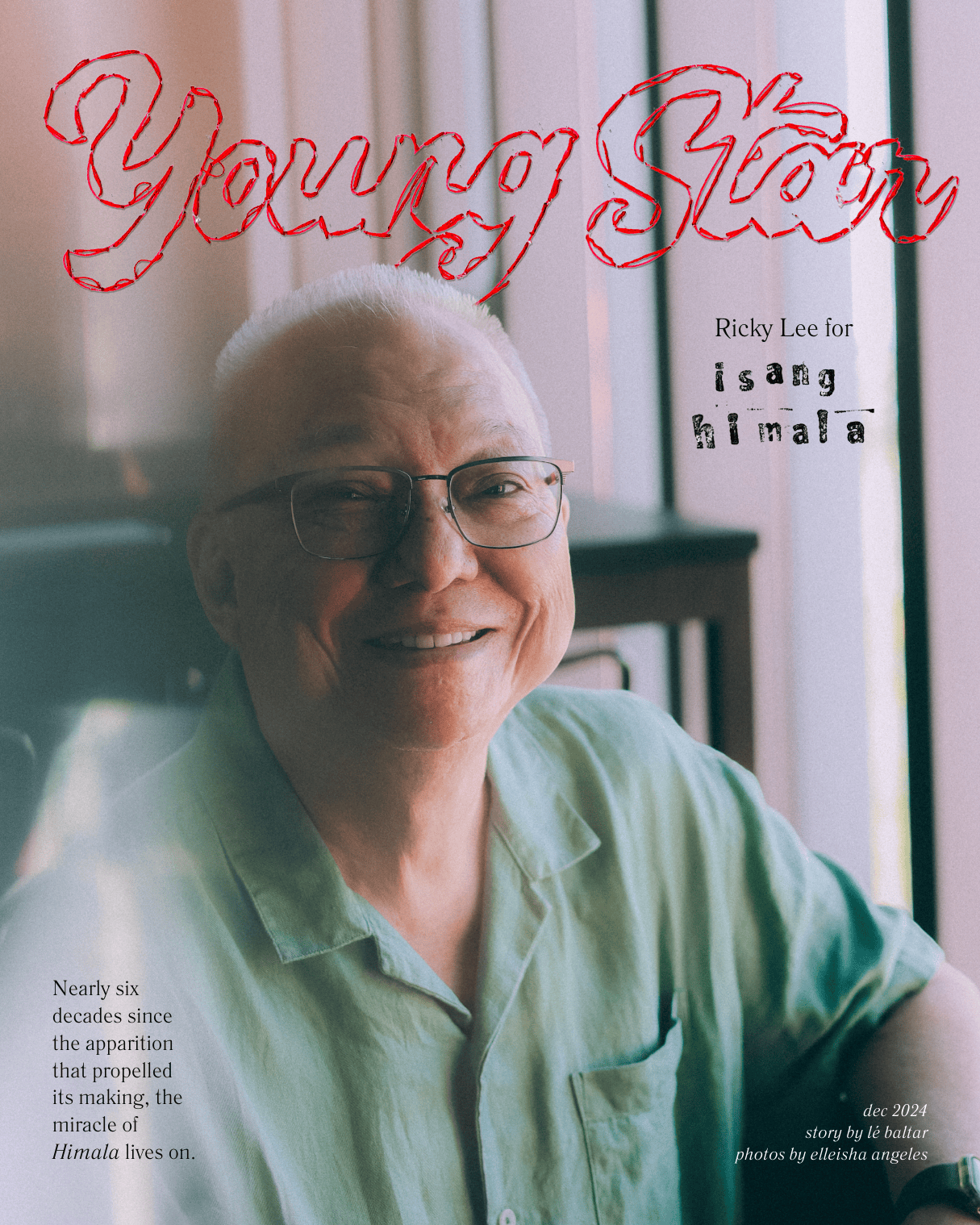

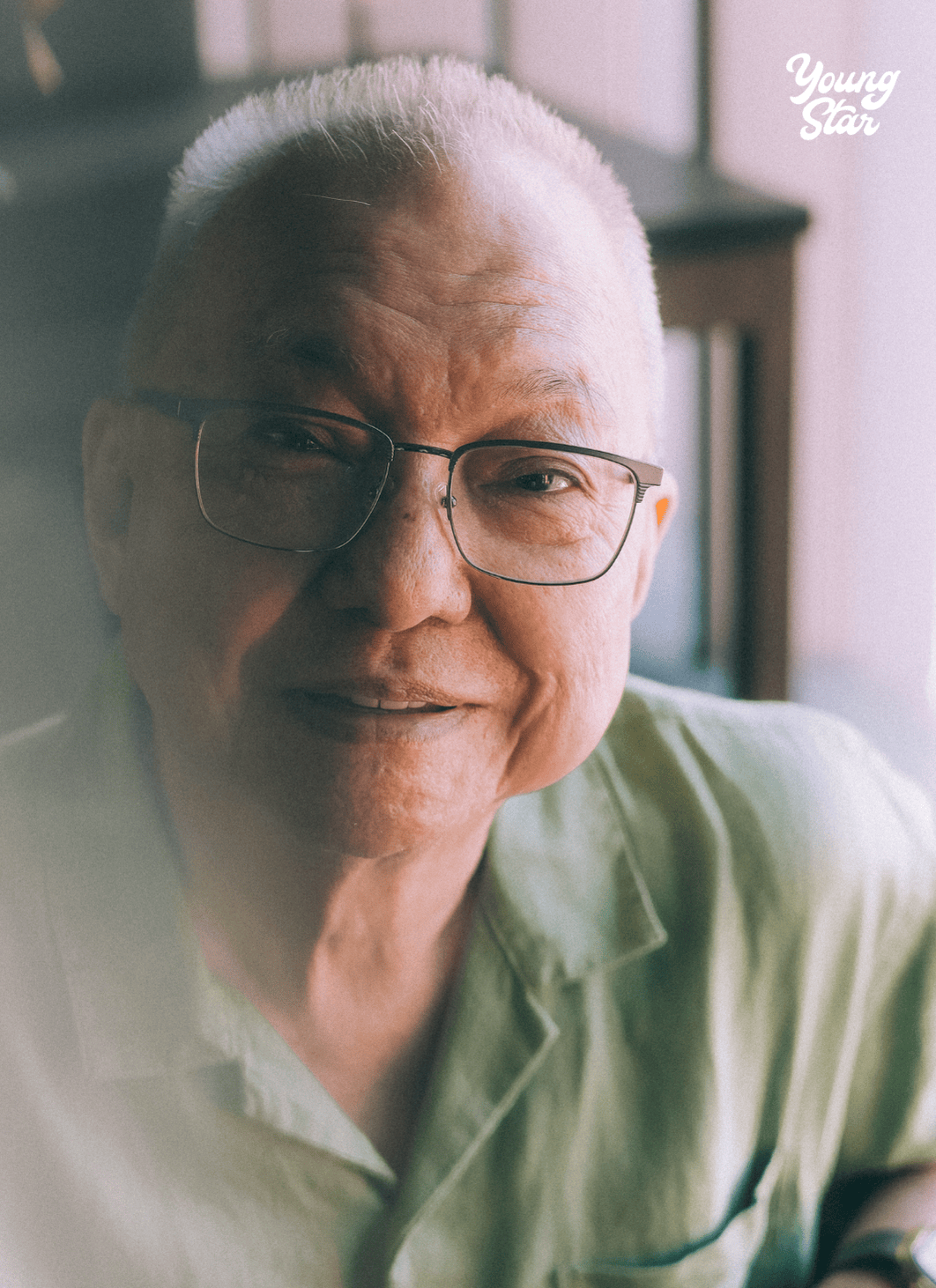

Sometime in 1966, eight schoolgirls on their way home claimed to have caught sight of the Blessed Mother on a hill in Cabra, an island north-westernmost of Lubang, Occidental Mindoro. After the holy sighting, the principal seer, Belinda Villas, became a faith healer. People began turning to her to assuage their illnesses, an impulse that was no longer a surprise for a country mired in abject precarity at the time. The child’s healing prowess quickly became commercialized, according to Ricky Lee, who wrote a script based on the divine act a decade later, in 1976, shortly after spending life behind bars due to trumped-up charges.

Lee peddled the material to several producers but was met with rejections, for it was said to be too serious and depressing. This, until the early 1980s when the eminent screenwriter learned about a script contest under the Experimental Cinema of the Philippines, which was among the projects of the so-called conjugal dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos.

Titled Himala, the material won and drew the attention of director Ishmael Bernal. Nora Aunor, then at the peak of her career, took on the iconic role of Elsa, whose visions would amass idle worship from the people of Cupang, a town enmeshed in sand and heat, populated by dread and desolation, and bound by desire or the lack thereof. The film premiered at the 1982 Metro Manila Film Festival (MMFF), sweeping the festival awards, grossed around 30 million pesos, and went on to compete for the Golden Bear at the 33rd Berlin International Film Festival, the first for a Filipino title.

Himala was a sweeping collaboration between three giants, all conferred as among the country’s national artists for film, in what is arguably the second golden age of Philippine cinema, however young this cinema might be, against the backdrop of Marcosian rule and American imperialism, retold and touted as part of every local cinematic canon possible.

Since then, the Filipino audience has weathered many storms, literal or otherwise, put up with a drug war and a global pandemic, and seen the meteoric rise and fall of populist regimes, including the return of another Marcos to power. But the miracle of Himala would not die; if anything, it cycled through many lives.

In 2003, Tanghalang Pilipino adapted the film into a stage musical, boasting a solid cast of 20, led by May Bayot-De Castro as Elsa, with writing by Lee, music by Vincent de Jesus, and direction by Soxie Topacio. But two years before that, Lee was already gearing for a sequel to the 1982 film, and had informed Aunor about reprising her role to reflect the physical and moral changes the character had gone through. He came up with a first draft, but it was shelved to give way to Himala, Ang Bagong Pagtingin sa Mukha ni Elsa.

With a larger ensemble of 40, the musical was restaged by the same theater company in 2006, and had an abridged version shown at the Asian Contemporary Theater Festival in Shanghai, China, in 2007. Five years later, Himala became the first title to go under the ABS-CBN Film Restoration Project, the result of which premiered at Venice Classics as part of the festival’s 69th edition. When the musical welcomed its 10th year in 2013, Touchworx Group Inc. and the Philippine Educational Theater Association (PETA) mounted a concert, still under Topacio’s direction.

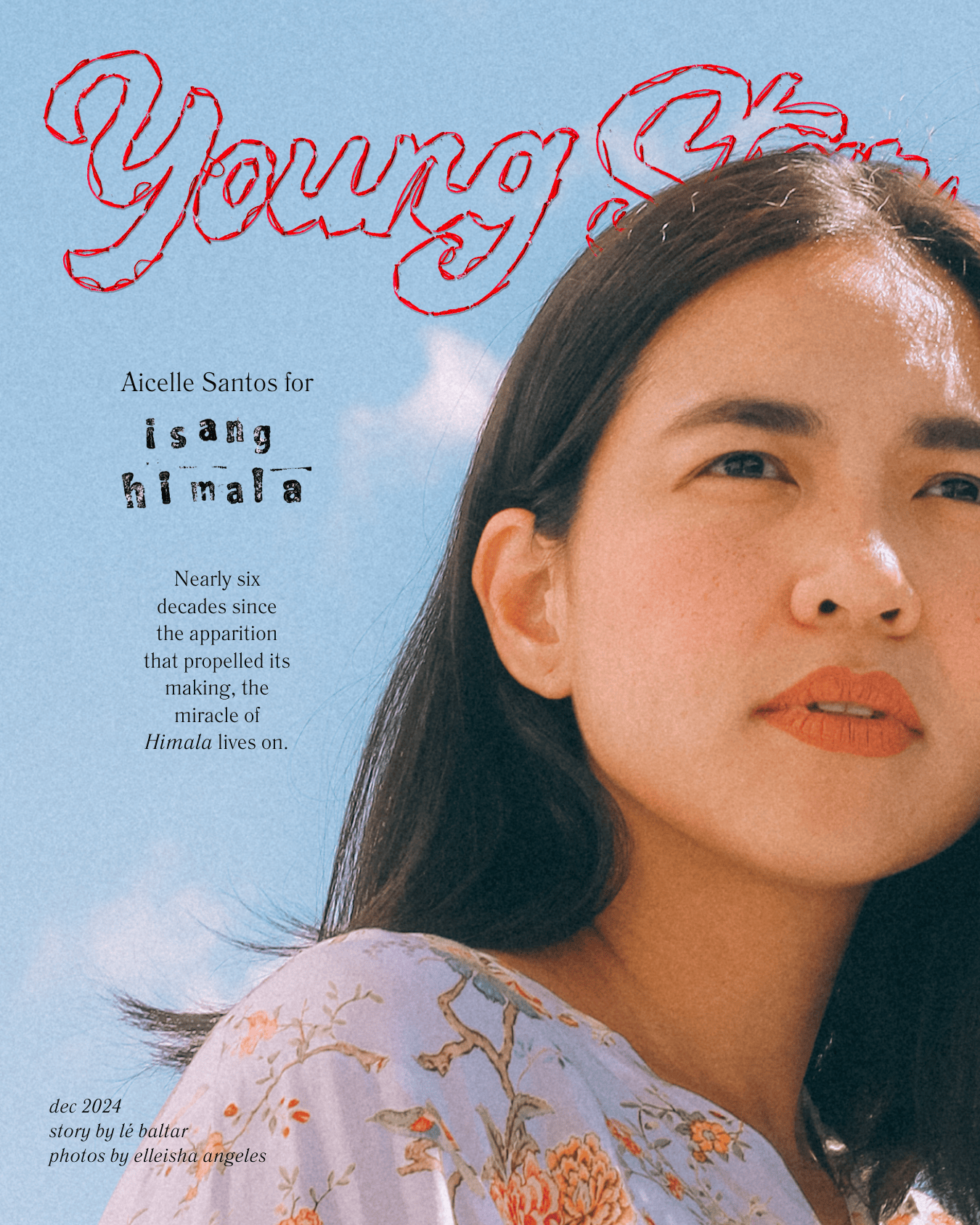

By 2018, the show had a renaissance through the efforts of The Sandbox Collective and 9 Works Theatrical, with Lee and de Jesus still sharing credits in the libretto, but under a new director in Ed Lacson Jr. and a fresh cast, top-billed by Aicelle Santos as Elsa. Rebranded as Himala: Isang Musikal, Lee said there were pivotal artistic recalibrations in the staging, including the heightening of Elsa’s manipulative side and her relationship with the photographer Orly, the omission of the blind character, forgoing microphones for the actors, alterations in the vocal arrangements, and a more immersive treatment of the audience as though they were people of Cupang.

That fine-tuning favored the show as it won big at the 2019 Gawad Buhay Awards, reaping eight trophies, followed by a rerun that year. These adaptations also had a filmed version, shot under four directors: Treb Monteras II, Paolo Villaluna, Ice Idanan, and Bradley Liew. Though inaccessible until now, the material had already been edited.

This year, the masterwork finds new life at MMFF’s golden edition—as a musical film, aptly titled Isang Himala, under the reimagining of Pepe Diokno, in a swift return to the festival after last year’s GomBurZa. The film is set to come out this December.

I spoke to Diokno, alongside other cast and crew, on a Tuesday afternoon at The STAR’s new headquarters in Parañaque. His getup, a Randolf barong and a pair of dark blue pants, accentuate his fine, mellowed-out presence. The director tells me he first encountered Himala as a required viewing in film school, and has since been changed by the imposing scale of its endnote. “It really moved me and you walk away with that iconic line ‘walang himala’ stuck in your head.”

But it was in the 2018 musical that Diokno really absorbed that decimating feeling, and was left overrun with tears. “Because I think what the musical does is it shows us, first and foremost, a different side of Elsa. It questions sort of who Elsa is,” he says. “Second, the musical is not just about Elsa, it’s also about the people of Cupang. Like you watch the play and it’s the townsfolk that really come alive. And so it’s really a mirror about our society that’s still relevant until today.”

That became a turning point for an idea about a movie musical to seep into his thinking, never mind the six-year gap towards its fruition. Replete with excitement to hop back on the genre, following musical revivals like The Color Purple, Mean Girls, and Wicked, Diokno sent Lee a message around March this year about his intention of turning the original material into a musical, and the latter immediately said yes.

Like many filmmakers shaped by the master screenwriter, Diokno was once Lee’s mentee. Before the pandemic, Diokno would actively participate in Lee’s workshops, held every Sunday in the mentor’s own house. “He taught me a lot about scriptwriting but also about living life as a creative. I really owe him a lot,” the director admits. “He’s created this community of filmmakers from his workshops. We’re really sort of like a family. Maybe that’s why he said yes.”

Diokno soon put together a pitch deck, detailing how he would pump new life into the existing title. “Malinaw sa vision niya na may sarili siyang treatment sa pelikula,” Lee says. “Na-impress ako doon kasi para sa isang writer na gaya ko, ayaw ko namang nakikita na ‘yung ginawa ko, inuulit lang nang inuulit, siyempre you want it na nare-reimagine, na nagkakaroon ng ibang approach, and yet the same. Faithful and yet hindi faithful.”

Fast forward to actual production, which stretched on for 16 days. For Isang Himala to come across as a film—not filmed theater—Diokno strived for the same visual spectacle and production quality as Gomburza, and kept the same creative team he had before. He was also adamant about preserving the immersiveness of the 2018 musical, which meant forging an entire community, an entire Cupang, from scratch.

Sure, they could have just shot the movie in the heat, in the sand dunes of Ilocos as the 1982 title, but that would mean compromising the actors’ vocal performances, which were all recorded live (de Jesus is still doing the music, but with a different treatment). Instead, they built a working house and a town up in the mountains, among many things, inside a studio. They also produced their own lights, which had been beneficial because they were able to shape it to their liking and “make the scenes emote.” At times, Diokno would even be caught off guard by cats, goats, and pigs casually present in the set.

In this retelling, Diokno reimagined Cupang, itself a character in the film, as a mining town instead of an agricultural town. “Because we want to show that it’s not about drought, it’s about scarcity. This is about what we have done to our world na talagang we exploited it to a point that walang-wala na tayo.”

Diokno’s vision of Isang Himala being equally about Cupang and Elsa also largely factored into keeping the 2018 cast intact. “They did a lot of work trying to get the right group of people together and they had formed the community,” he says. In fact, the cast still maintained a group chat at the height of the pandemic. “They know their characters by heart, every single one of the actors.”

Among those actors is Aicelle Santos, now set to reprise her gigantic role as Elsa. When she took on the part six years ago, after seeing PETA’s 2013 concert at a juncture when she was just beginning to venture into theater, she had no idea about the possibility of a movie musical. It was around July this year, seven months after giving birth to her second child, that she got wind of the remake. She cried over the news. “It’s big shoes to fill,” she tells me.

Santos, softly spoken yet articulate, frets over the megawatt expectations set by the movie’s predecessor, on top of the fact that she had taken a long break from the spotlight. Her silver-screen credits include a minor part in Loy Arcenas’s Ang Larawan and a role in Gino Jose’s 2016 short Waivers. “Ang tagal mong napahinga. Your stamina, your voice, (you) felt, nag-iba siya.”

Before production began around September, Santos threw herself into preparation. She had physical and vocal training, the latter with help from Sweet Plantado, also part of the film and a member of the vocal group The Company.

She’s also wary of her approach to Elsa, considering the temporal distance, her acting inflections on stage and on screen, among a whole lot of fixations. “Though I did it before, it’s (been) five years. Andaming nangyari sa buhay namin. Marami kang bagong pakiramdam, marami kang bagong pananaw,” she recalls. “I think my interpretation of Elsa is more mature. Mas maraming karanasan. Mas malalim.”

“The challenge of also filming it na paulit-ulit,” she continues, “you have different takes, different angles, as compared to doing the musical theater, kumbaga dadaanan mo from the beginning to the climax to the end. Mayroon kang sinusundan na emosyon. Dito, ‘okay, cut, next angle tayo.’ So you have to hold it and then you have to do it again.”

Everything came together after she realized the task “boils down to knowing the truth, being in the moment, and just telling the story.”

Whether or not this role would generate momentum for Santos post-MMFF is up to fate’s hand. “Like Himala, which just landed on my hand, I really don’t know.” But it excites her. “Hopefully I could really be back.”

Bituin Escalante, who has already starred in another musical film, Lav Diaz’s Ang Panahon ng Halimaw, also reprises her role as Aling Saling, Elsa’s mother, in the 2018 show. She had seen the original movie via a video rental shop called Video 48 sometime in the past, recounting how she had “never seen a quiet Filipino film that had so much to say.”

She thought she would breeze through the part, but figured otherwise. “It’s a great learning experience in letting go,” she surmises. “When you’re building a character in theater, and you’re given liberties to create the character that you were given, it takes a certain amount of adjustment and letting go when you shift to film. Because sometimes you create these big backstories and these big motivations that won’t appear on screen.”

What makes a whole lot of difference, though, is that Escalante has long quit smoking since the first time she did the stage musical. She’s more vocally ready now (cases in point: a major concert to mark 25 years in the scene, then a restaging of a musical she’s been part of before). “Mahirap lang talaga ‘yung conditions ng shoot because we were in an enclosed space and dust in open air is dust that flies to the head.” They were in a dust cloud, so to speak. “But when I saw the film, the dust was worth it. Ang ganda ng atmosphere, ang sukal.”

Escalante says her Aling Saling this time around leans more on the softer side, forgoing her previous notion of the character who’s reluctant to give and receive affection. “I’ve always thought of her that way. She adopted Elsa, like so many others in this society who adopt, hoping that someday someone will take care of them. It’s not to care for someone, it’s to be taken care of.”

When I press her about the timing of the remake, Escalante asserts there shouldn’t be any question about the film’s relevance. “I think we go back to the classics anyway,” she explains. “The themes or settings are just modernized, but we go through the same things over and over. I’m not saying we’re lucky, but we’re still stuck in the same rut.”

“You make money from the miracle and you suffer from the miracle. It’s the human condition,” she continues.

Part of the reason why Himala endures is the human drama that Ricky Lee muscles into the story: a mother raising a child of another, a woman returning to a town she once loved but has long forsaken her, a romance disrupted by numbing hardship, a friend and loyal devotee whose faith cannot spare her own children from death, and an entire townsfolk in search of possibilities. These conditions still recur in present-day Philippines, as though Lee has foreseen it.

“‘Yung problemang tina-tackle (ng pelikula) before tungkol sa pangangailangan ng tao na may makapitan sa sobrang hirap ng buhay, totoo pa rin ngayon o baka mas totoo pa nga ngayon,” Lee says. “Kailangan nilang may kapitan, kailangan nila ng strongman, kailangan nila ng magsasabing, ‘Akong bahala sa ‘yo, may kakainin ka bukas.’”

When we spoke, Lee had just returned from his trip to Iloilo, after a talk at a film festival. Last September, he released his latest novel Kalahating Bahaghari, completed within five months, at the Manila International Book Fair. He also worked on another MMFF entry, Zig Dulay’s Green Bones. Now, he is primed to work on a stage musical adaptation of Moral, the 1982 masterwork directed by Marilou Diaz-Abaya, while writing his memoirs and touring campuses for Himig ng Isang Himala, a documentary on the making of the MMFF title.

Such is life for someone who has tirelessly forged foundations, if not planted every brick and tile, for many household and flourishing names in the local scene. Lee commits to this lifelong project because local cinema, as he puts it to me, has yet to recuperate from heavy losses in the last few years. “Nilalakasan ko ‘yung drive ko lalo kasi maski na may mga kumikita na ilang pelikulang Pilipino, bagsak pa rin siya commercially,” he shares. “Lahat tayo (dapat) magtulungan para mas maraming taong manood ng pelikulang Pilipino, maski hindi natin pelikula.”

Ticket costs for movies have been on a steep rise since the pandemic, forcing the viewing demographic to change. In fact, a recent survey states that the D and E markets, to which Filipino masses belong, no longer watch local movies in theaters. Be that as it may, Lee reckons nothing seems impossible. “Pwedeng maghimala. May himala.”

Lee, past this, wants to dispel notions that only mainstream genre films could turn a profit and be included in the film festival circuit. “Dapat dumating ‘yung time na wala nang regional film or Manila film, lahat pantay-pantay. Lahat ng mga lugar sa Pilipinas, lahat sila sentro ng paggawa ng pelikula. Sana dumating ‘yung time na lahat tayo gumawa ng pelikula sa boses natin, sa genre na pinakabagay doon sa vision natin and i-appreciate ng festivals natin.”

Diokno, meanwhile, says the local film industry, especially in the age of streaming, should practice models patterned after some countries like France and Australia, which require streamers to put back a portion of their profit to producing local content. “Because they have noticed that if they don’t compel the streamers to do that, then (they) will just produce Hollywood.”

“Imagine if we stop making Filipino films, then it would be a waste,” he points out. “I think we’d be much less of a people if we didn’t have our own films.”

Life in the Philippines, like local cinema, is forever in flux. Struggle is our default. At times, we pray for miracles to wrest what is perpetually out of reach. But in the harrowing ending of Himala, Elsa tells us it’s not a matter of whether or not miracles exist. What really matters is what we do next, in spite.

***

Produced by Andrea Panaligan

Story by Lé Baltar

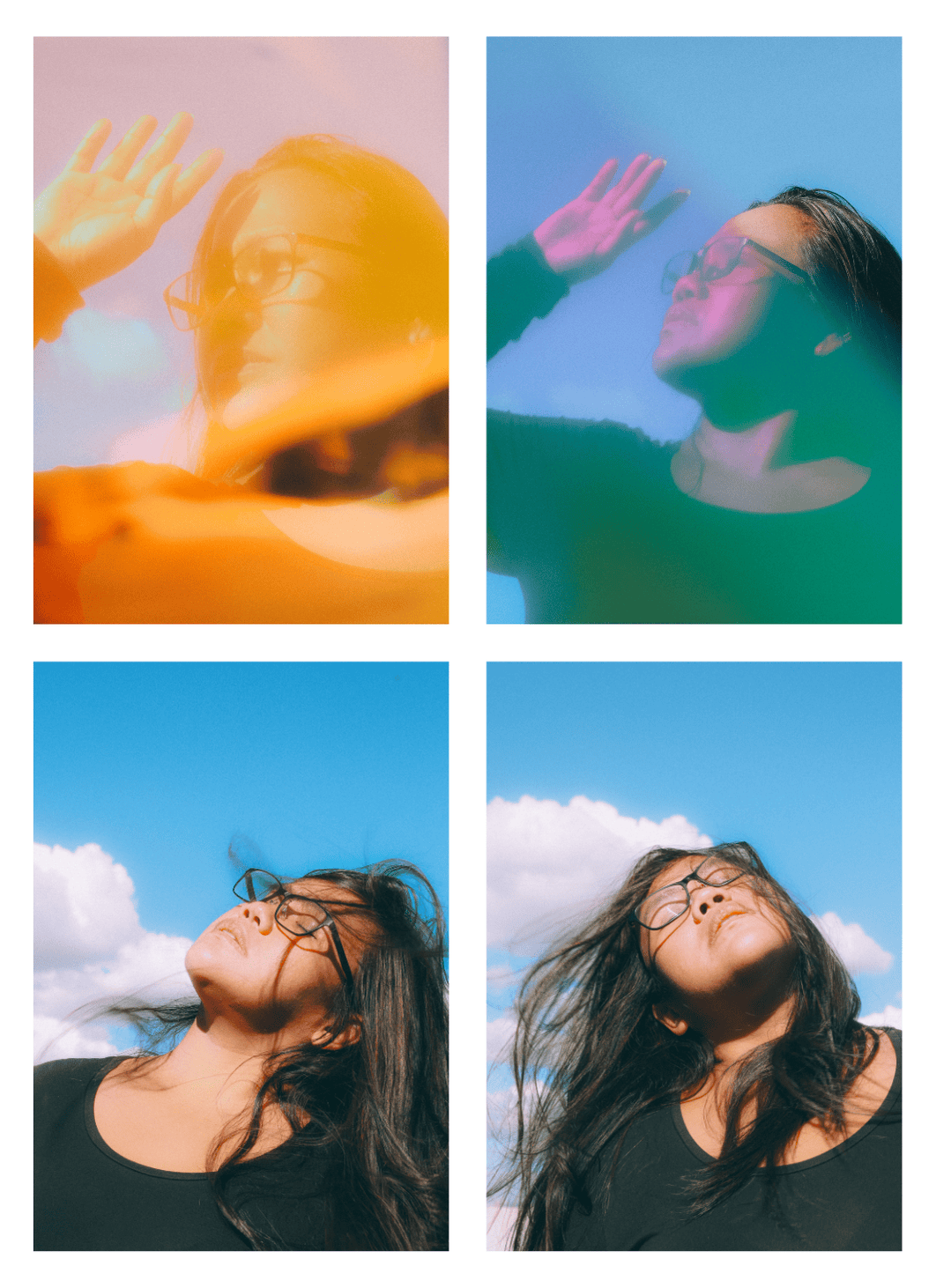

Photos by Elleisha Angeles

Special thanks to CreaZion Studios and Anthony Abad