Impressionists have a TikTok moment at National Gallery Singapore

For National Gallery Singapore, which marks its 10th anniversary this month, it’s not unusual lately to see social media influencers posing and prancing on the Padang atrium or the walkway joining the old City Hall and Supreme Court buildings. They’re probably recreating scenes from BTS member Jin’s Don’t Say You Love Me video, recently shot in the museum with the savvy participation of the Singapore Tourism Board.

But today, there’s another celebrity sighting: National Gallery unveils “Into the Modern: Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,” a star-studded collection of over 100 artworks by 25 key artists, a whole room devoted to Claude Monet (17 works), and Southeast Asia’s largest-ever showing of French Impressionists.

A splashy staircase bedecked with Monet’s “Cap Martin, near Menton” leads you up to the second-floor gallery, where head curator Phoebe Scott guides us to the first landscape. She’s immediately swamped by a sea of cameras and GoPro recorders.

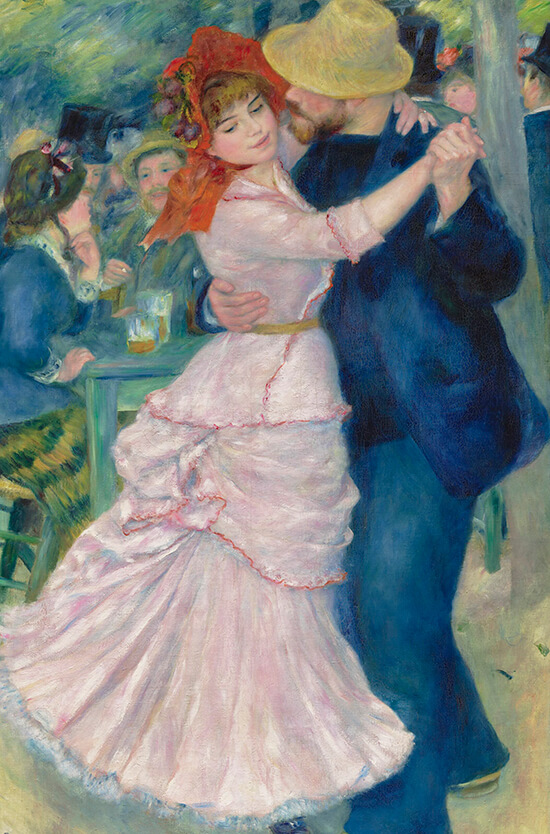

It’s expected, with such big names. “Into the Modern” takes us through seven rooms cascading with classic works by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Édouard Manet, Paul Cézanne, Théodore Rousseau, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, Henri de Toulouse Lautrec, Henri-Fantin Latour and others. Your head whipsaws between Renoir’s “Dance at Bougival” (1883), ink sketches for Manet’s “Olympia,” and an array of Monet’s meditative “Grainstacks.”

This star-studded gathering, most of which recently toured Melbourne, is on loan from the Museum of Fine Arts Boston’s world-class collection, in partnership with MFA’s Julia Welch and Katie Hansen. Distinct from the Melbourne show, “Into the Modern” comes with a brand-new curation under Scott and her colleagues.

As National Gallery director Dr. Eugene Tan said, opening the show, “For us, one of the key questions when a traveling show comes to the museum is, why should we be looking at this art in Singapore now?”

Indeed, it’s a question I myself asked my old friend ChatGPT before visiting the gallery. The AI chatterbox answered: “In an age of scrolling feeds and instant imagery, audiences connect with how Impressionists captured moments—transient glances of light, weather, and feeling. Monet’s shifting skies or Degas’ blurred movement feel like snapshots before photography became common.”

Dr. Tan expanded on AI’s surface-y analysis: “Impressionist artworks are among the most enduringly popular of the modern period. They have a poetic, visual appeal that has lasted till today. They’ve been so widely reproduced that they’re very familiar to us even now, and sometimes, because of that familiarity, we can lose sight of how radical and challenging they were at the time that they were produced.”

Phoebe Scott picks up the story as we enter the first section, “Seeking the Open Air”: “The fact that these painters could even come to the forest at Fontainebleu to paint was evidence of modern change. The new railway network suddenly connected faraway parts of France, allowing many more artists to travel to the region. The invention of painting tubes in 1841 allowed them to easily transport paint with them, and actually paint in the outside world.”

Radical technology, as portable as today’s iPhone. Check. But it’s what these artists saw and chose to paint that matters. No longer locked into religious, historical or royal subjects, the likes of Pissarro, Rousseau, and Manet took to the fields and sea sides and depicted real life, real people, the sensations of light, nature, and the changes taking place within those natural environments as modernity rolled in.

In the “Plein Air Impressionism” section, we learn how the movement coalesced. By 1874, dissatisfied with the French Salon shows, with new works splattered on walls with no sense of focus or curation—the 19th-century equivalent of a photo dump—the new artists put on their own group show, calling themselves, unmemorably, “The Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors and Engravers.” A drubbing of their works by a French critic provided the name that stuck: “I was certain of it that, since I was impressed, there had to be some kind of ‘impression’ in it,” wrote Louis Leroy. “And what freedom! What ease of workmanship! Wallpaper in an embryonic state is more finished than this seascape.”

We move through “Labour and Leisure on the Water,” where the curation makes a somewhat tenuous connection to Singapore land reclamation, noting how Impressionist works over time reflected the effects of canal dredging on nature. “Into the Modern” does incorporate extra “educational zones,” large hanging screens to provide historical context, as well as drawing connections and an influence on Southeast Asia, such as the printmaking techniques of Singapore artist Lim Yew Kuan. Yet, as Scott points out, “it can be very difficult to say a Southeast Asian artist is an Impressionist, so to speak. (However) we do see certain legacies that come from Impressionism (disseminating) into Southeast Asia.” One can even see it in the gallery’s ongoing exhibit a floor above, “Between Declarations and Dreams,” where western artists are shown influencing Juan Luna, Hidalgo, and Raden Saleh’s “Forest Fire.”

The fourth room delves into “Shared Ambitions,” showing the mutual influences of the Impressionists, with Pissarro standing out as a consistent mentor participating in all eight group shows. A boom in Paris nightlife leads to “Modern Encounters,” where Impressionists steered their brushes and canvases to tackle cafés, bars and dance halls. Movement was everywhere, from Renoir’s almost animated, feathery brushstrokes to Manet’s “Street Singer” (1882).

Room five, “Reimagining the Commonplace,” takes time to establish a few female artists among the largely male barkada, with equally striking works by Mary Cassatt and the immediacy of Berthe Morisot’s flowers; pair that with the distinct concentration of Latour’s flowers, and the way Cézanne was already starting to branch into a more radical reexamination of form and space that would later influence Cubism.

Personally, I preferred returning to the exhibit for a more leisurely, reflective look after the hubbub of the fast-moving tour was over. There you can marvel at the rare snowscapes of Monet (likely inspired by Japanese woodblock prints), absorb how Pissarro generously shared his forest pigment choices (emerald green and Naples yellow) with aspiring Impressionists, or how different are the rugged mountains depicted by Cézanne versus Gauguin.

The final room is fittingly reserved for Impressionism’s acknowledged master. “Monet: Moment and Memory” shows how the artist explored all the movement’s lessons, and expanded on them. Borrowing from ukiyo-e prints (printmaking was another technological innovation that ran parallel with Impressionism, along with photography, which can be seen influencing Degas’ curiously cropped compositions of dancers), Monet retreated into the Japanese fantasia of Giverny to paint waterlilies and bridges, or ventured to explore grain stacks during different hours of the day, building up gradual masterpieces of light, color and shading that still thrill the viewer. Memory was as important as first impressions by this point of Monet’s journey: “Whatever was begun en plein air was likely also finished in the studio,” notes Scott. “Grainstack (Snow Effect)” on display at National Gallery was first purchased by “a young couple from Boston who visited its exhibition in Paris. They purchased the work as a honeymoon present to themselves and, 100 years later, it was given to the Museum of Fine Arts Boston to celebrate the centenary of the museum.” The bulk of the collection was donated by Bostonians who no doubt yearned to see their private acquisitions join the museum walls along with other masterworks.

As a final nod to Impressionism’s modern-day relevance, the exhibit closes with the only known film footage of Monet, shown dabbing a canvas while looking to his left, with “the world’s longest cigarette ash” dangling from his mouth, looping over and over. It’s a choice to cap the show that hurls us back into the modern, the age of Instagram and TikTok loops and endless photos on our phones. I did ask our curator, jokingly, how it felt to be competing with Jin for attention on the National Gallery steps, and she said, “If it brings more people into the museum to see other things, I think it’s great.”

* * *

“Into the Modern: Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston” runs until March 1, 2026 at National Gallery Singapore. For tickets and enquiries, visit info@nationalgallery.sg and www.nationalgallery.sg.