Enrique Marty, at home with the uncanny

Enrique Marty’s portrayals of family aren’t sentimental. They’re uncanny. At a distance, his paintings appear deceptively intimate; but up close, compositions of an idiosyncratic home-life start to reveal tense points: an unwarranted expression, an uneasy unrelenting grip, a silvery gleam in the eye, a scream that holds another scream inside it. Here is the uncanny as a convulsion of the ordinary.

Last Aug. 10, the curator Kristine Guzmán held a talk with Marty at the opening of their exhibition “Project Belonging: From There to Here” at the Ateneo Art Gallery. Marty grew up in Salamanca, Spain while Guzmán is a Filipina migrant, born in Manila and now based in Valladolid. The conversation spun around ideas of a family—how art-making is, for Guzmán, a kind of therapy, or for Marty “a way of exorcism,” to work through the strangling negativity of intimate dynamics.

“My parents had a terrible relation between them,” he confesses. “The family is a very important symbol, because everybody has a family... and normally we don’t choose (them).” In troublesome situations, we only manage to deal with either their absence or their unbearable company.

The family as an affective microcosm is what ties together the two parts of “Project Belonging.” The current presentation, which is titled “The Foreign in the Familiar,” focuses on Marty’s works, with a few mixed-media pieces by the Filipino migrant artists Isabel and Alfredo Aquilizan. Guzman’s curatorial tactic is to reverse the arrangement in November, with the Aquilizans taking over the space in the forthcoming presentation called “The Familiar in the Foreign.”

This is Guzmán’s first exhibition in the Philippines. Initially trained as an architect, she moved to Spain in 1999, shifted tracks and pursued curatorial work at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León (MUSAC) for close to two decades. “I felt connected with the (Aquilizans) because they left (the Philippines) and they’re always talking about immigration in their works,” says Guzman. “They’re always talking about the idea of home, and so is Enrique. But then with the Aquilizans, home is more idealized, while with Enrique, it’s more dysfunctional. He’s (showing) the dysfunctional family.”

Marty describes his mother as a very theatrical figure—“like a baroque painting”—while Guzmán muses that the mother’s dramatic temperament must have come from a life of being confined to the household: the space of responsibility and limited possibility, the province of the unbearable ordinary. She was a housewife to a military man. During the talk, Marty plays a video animation where we see his paintings set in motion: his mother in a kitchen firing towards an unseen target on the left; then, his father in open fields, firing towards the right. The sequence plays repetitively.

“It’s like a duel,” says the artist. “But he is in the countryside and she is inside the house. They are not in the same place. They’re not shooting each other. You are making the scene in your brain.”

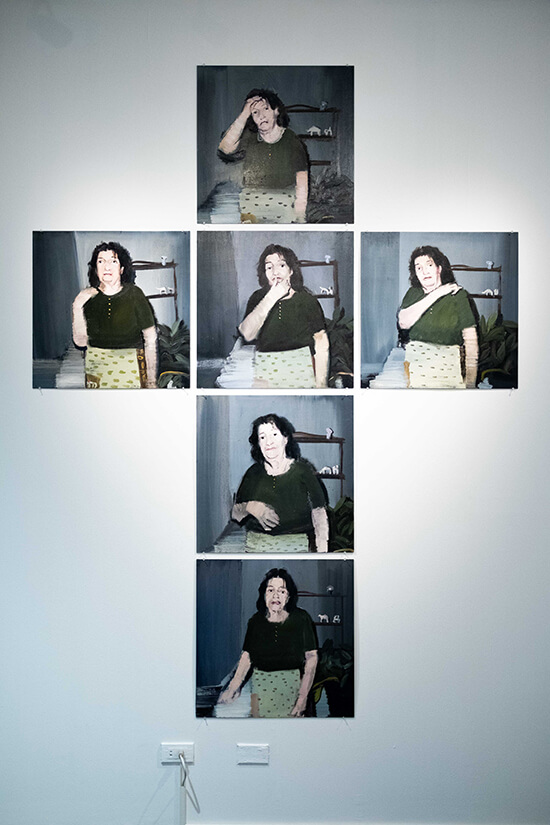

And Marty seems to relish the ways a sly, conspicuous image casts a shadow in the mind. Small-scale paintings mounted in grids recall the peculiarity of all family photographs, except there’s something stranger hovering. A silhouette lingers where a man pulls a child’s arm at a frightening angle. Birds appear; faces regard us intently with a painterly blur.

Most of Marty’s images carry the hurried contingency of a sketch. “I call it snap painting,” he says. He takes Polaroid photographs as references and then paints them fast—“very fast, almost like a performance.” These pictures, static or animated, want to get close to the Freudian uncanny, or the repressed content that comes back nudging, again and again, at the surface of daily life. The artist is interested in the psychological and the philosophical, from Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, to Friedrich Nietzsche—those erudite males who dissected humanity’s shadows with their analytical scalpel.

About a century ago, it was the Surrealists who played with the uncanny. Surrealist gestures staged the ordinary—a glove, an ear, a spoon with a pointed edge—as scenes with veiled convulsive charge. They turned to hysteria to create a semblance of the marvelous. But Marty’s uncanny grounds us in the scene of the domestic—there in the kitchen sink or the living room, where his mother is smiling in a video, wearing the Joker’s mask. Tellingly, unheimlich, the German word for uncanny, comes from the term heimlich, or homelike.

While most of the works on view exert a visual appeal—as if to say, yes, the uncanny can be pretty, too—it was also interesting to learn Marty’s clever relational interventions into the family home. Once, he manipulated his parents’ wedding photograph, made their eyes monstrous—and yet, the married couple never noticed, for they never looked at the picture hanging on the wall.

These ploys continued when he made sculptural replicas of his parents, but changed up the scale so that his military father became much shorter. The relationship became better after that, Marty tells us, before admitting that it also became worse eventually.

Still, the scene became a fond memory: “It was funny to see my two mothers watching TV on the sofa,” he says. Art may not be therapy all the time, but it does invite us to sit more comfortably with strangeness.