After the celluloid rush: Archiving Cesar and Mario Hernando’s belongings

One night, archivist and musician Erick Calilan received an urgent call: the entire contents of the apartment of renowned filmmaker Cesar Hernando and film critic Mario Hernando were to be emptied, and decades’ worth of their belongings were up for the taking. Calilan had a couple of hours before this film archivist’s dream of a treasure trove was to be disposed of.

While history tends to be told in terms of actors and auteurs, the Hernando brothers made significant contributions to Philippine cinema behind the scenes.

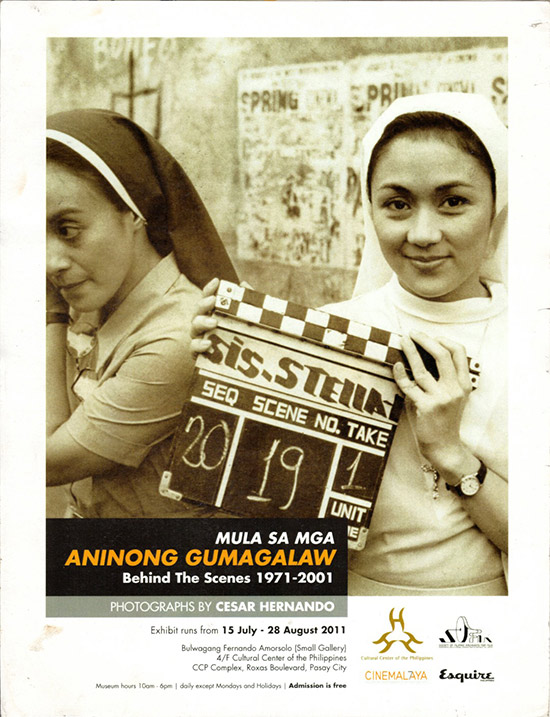

Cesar’s production design set the stage for films such as Mike De Leon’s Sister Stella L. (1984), Kisapmata (1981), and Lav Diaz’s Batang West Side (2001). He directed several short films as well; I find it futile to concisely describe Cesar’s experimental short Botika Bituka (1987) as anything short of wasak na wasak.

It’s sad to me that some of the most remarkable artists of our time are only recognized post-mortem. As if they could hear these heaps of praises from their grave! It comforts me that Cesar was celebrated while he was alive, with Cinema Regla’s special screenings of his short films and “The Unseen Cesar Hernando” (2018) in Archivo 1984.

His brother, Mario Hernando, was one of the 10 founders of the Manunuri ng Pelikulang Pilipino, which holds the annual Gawad Urian awards.

Even in the latter years of his life, he wrote and recognized younger generations of filmmakers and how they challenged the status quo of Philippine cinema. His writing championed a form of criticism that was critical not just of a singular film as art, but as a narrative working within the larger systems of industry and culture that produced it.

Mario passed away in 2017, while Cesar passed away in 2019, both leaving indelible marks on Philippine cinema. With these rich histories in mind, Calilan set off on a great endeavor: sifting through their belongings, which are an addition to his already extensive archive.

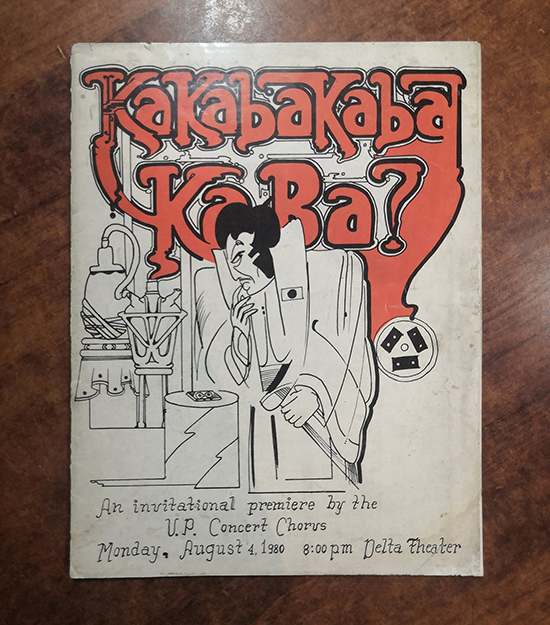

He arrived at their former apartment to find an overwhelming array of boxes that the Hernando brothers had left behind. There were posters, artworks, books, scattered notes, VHS tapes, paintings, antiques, props, and other curios.

The Hernando family had already moved many of the items to archives and other relatives, while the rest were left to Calilan. There was much left behind the locked doors of the apartment, but the contents of the garage alone were enough to fill up the L300 truck that Calilan hired for the occasion.

“We were happy that we were able to save personal belongings of Cesar and Mario, hoping that we could preserve whatever is valuable to researchers and material archivists, and as well as for the family, but at the same time anxious about what will happen to the other belongings that have been left and locked up inside the main house,“ wrote Calilan on Facebook, where he frequently posts updates about his archives.

Independent archiving efforts are crucial nodes for remembering, despite the relentless entropy of time. It’s worth a sigh of relief when a rich spring of memory is saved from being consigned to oblivion.

So far, Calilan has unearthed color negatives of Lino Brocka’s Orapronobis (1989), Ninoy’s funeral, and Sagada landscapes. Cesar was a prolific photographer who captured the movie set in all its triumphant chaos. (He also saved the exhibition print of “Mula sa Mga Aninong Gumalaw: Behind the Scenes 1971-2001,” which was held at the CCP in 2011.)

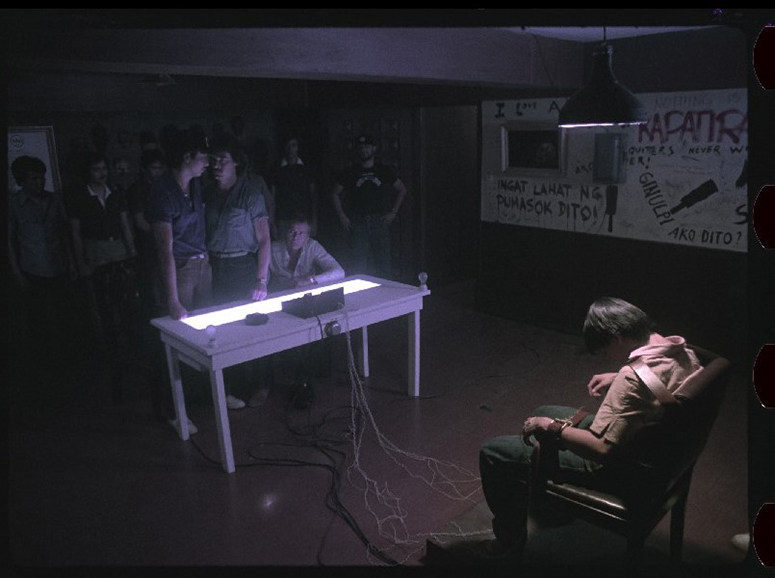

There’s a particularly striking photo of the nightmarish set of Batch ‘81, where Cesar Hernando constructed a caricature of 1931 Berlin for a school performance. The drumkit reads the Nazi concentration camp slogan, “Arbeit macht frei” (Work makes one free), as neophytes enact a twisted cabaret.

Perhaps this scene could not make it past the cutting room floor today, given how the internet tends to decontextualize film stills. Yet until today, Batch ‘81 still stands as a sharp depiction of how the insidious cancer of fascism indoctrinates the young. The devil in these details of Cesar’s production design sharpens the film’s claws against tyranny and machismo.

Considering that the Hernandos also advocated for Philippine film archiving, Cesar Hernando’s hard drives are well-organized by year and topic, with scanned photos from as early as 1939. Some libraries are organized according to year, while others are according to topic. Folders titled “Dona Sisang Various Birthdays,” “Studio Life,” “Portrait etc” hold interesting surprises that Calilan has yet to publish. I can’t help but feel like I am glimpsing someone’s inner private life, and the arduous task of drawing out the sum of these parts is up to the archivist.

Still, independent archivists such as Calilan are limited by physical space, resources and personal efforts. Calilan’s 700 GB of Philippine audio and music-related materials and the equipment used to digitize these were all his own. The Hernando brothers’ belongings are another set of narratives that he is taking on.

There are countless other archivists across the Philippines operating in a similarly Do-It-Yourself manner.

Who knows if the Hernando windfall would have otherwise eluded institutions’ eyes and ended up in a landfill? Independent archiving efforts such as these are crucial nodes for remembering, despite the relentless entropy of time. And it’s worth a sigh of relief when a rich spring of memory is saved from being consigned to oblivion.

Banner photo courtesy of Erick Calilan.