Limahong, POGOs, and the West Philippine Sea

History has a way of allowing you to take a hard look at yourself from a comfortable distance.

Events of five centuries ago have led us down a road that now finds us enmeshed with the very same marauding superpower. How can they be defeated—and can they even be?

Just 50 years after Ferdinand Magellan landed in the Philippines’ southern waters in 1521, a new and more drastic threat would appear in Manila Bay.

Imagine—in the same way folks with iPhones command Meta’s AI—a criminal enterprise masquerading as a legitimate one, pretending to be honest traders but which is, in truth, engaged in kidnapping, white slavery, prostitution, drugs, and torture of its workers.

The invasions of Limahong eventually led to the world’s first Chinatown.

Would this not-so-fanciful scenario be the story of the 16th-century Chinese pirate Limahong, or the POGO empire of Alice Guo and Cassy Li?

Separated by almost exactly 450 years, both enterprises are not so much different. As we enter the Year of the Wood Snake, it’s the perfect time to contemplate how very much alike they actually are.

Limahong began his nefarious activities on the southern coast of China, and like the offshore gambling businesses in this century, realized that more money could be made in the West Philippine Sea and, ultimately, on shore, by attacking and sacking Manila, its capital city.

Despite dire warnings to the city’s commander, one Martin de Goiti, Manila went largely unfortified and Limahong was able to land several hundreds of men outside the newly raised settlement before anybody noticed their presence. Today’s parallel would be the huge number of bogus birth certificates and fake government IDs given away to mainland Chinese nationals, thanks to bribes and influence-peddling. It allowed hundreds of illegal aliens (perhaps even thousands), then as now, to pass themselves off as Filipinos. Guo even had the gall to run for public office and win in a not-so-small town in Luzon, dress herself in Hermès, drive all-too-real gull-wing automobiles, and arrive by helicopter to her many ranches and mansions. The Philippine STAR, in fact, reported this week that this tomfoolery persists. A Chinese spy and his two Filipino henchmen were recently arrested with a trunkful of computer and communications equipment and communications in the back of their car. They were spying on Philippine military camps and installations when caught red-handed.

Like today’s POGOs, Limahong’s motley crew were a truly multinational group that included Japanese samurai (a certain Captain Sioco is named in historical documents), Portuguese deserters and Chinese sailors, recruited from up and down the coast. It’s clear from Guo’s escape route that she, too, had a network of underworld connections in the rest of Southeast Asia, in Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

View this post on InstagramA post shared by National Historical Commission of the Philippines (@nhcpofficial)

Limahong used his large navy carrying an estimated 800 to as many as 2,000 men to launch an audacious attack on Manila. It would be capped by the murder of the Spanish commandant Goiti, before the pirates were beaten back into the sea.

The depredations of Limahong—he would return to Manila a second time, succeeding in burning the great San Agustin church then—would set the course for the relationship between the law-abiding Chinese, the Spanish, and the Manileño indios for centuries afterwards.

This unexpected invasion led the Spanish colonial officials to zero in on Chinese traders and migrants and corral them in ghettos, such was their fear of another attack from what they had first perceived as friendlies.

It would lead to the establishment of the “Parian” outside Manila’s walled palisades that would eventually lead to the world’s first Chinatown.

The hero of the entire Limahong crisis was none other than Juan de Salcedo, grandson of the great conquistador Miguel Lopez de Legazpi. (Both warriors, the founders and defenders of ancient Manila, have been ironically immortalized today as the patron saints of Legazpi and Salcedo Villages in the Ayala-created Central Business District of Makati.)

Salcedo, who had been exploring northern Luzon from an estate called Fernandina, had rushed back to Manila to fend off the pirates. Mind you, Limahong was not of the irreverent, spritely mold of Johnny Depp playing Jack Sparrow in Disney’s Pirates of the Caribbean flicks. He was a one-man crime wave who was, nonetheless, highly intelligent and, by default, also extremely imaginative. Accounts from that period recount how he had been operating in the West Philippine Sea for some 10 years before his attack on Manila. Limahong would reportedly disappear “into thin air” after each raid, despite the fact that he commanded a large flotilla of ships. Limahong had his start as a small-time smuggler with ambitions; he would graduate into full-time piracy and create a waterborne mafia under his command. Despite the scope of his operations, he would continuously evade attempts of the Ming emperor’s Ministry of War to capture and destroy him. Speed and derring-do and a preternatural knowledge of sheltering coves and ocean currents allowed him to do so. Manila’s commander Goiti had underestimated his Limahong’s mastery of the November winds and he paid for it dearly with his life.

Limahong would escape momentarily after his attack on Manila and once again vanish just as suddenly as he had appeared. He would be discovered later by Salcedo’s spies in a makeshift settlement on the mouth of the Agno River in Pangasinan. It would foretell today’s artificial islands in the West Philippine Sea, created by the Chinese government’s engineering and construction companies. Like these military camps that have runways and barracks, they were built out of stolen Filipino sand and soil, dredged from the country’s seashore barangays by foreign multiple ships.

Today, Limahong’s example continues to loom large in the person of the Chinese “monster” ships, armored behemoths that attack with lasers and water cannons—as well as the squadrons of fishing vessels that swarm the Philippine Coast Guard and our own fishermen. These modern-day corsairs prevent Filipinos from pursuing livelihoods of their own in our own waters and plunder the country’s rich marine resources.

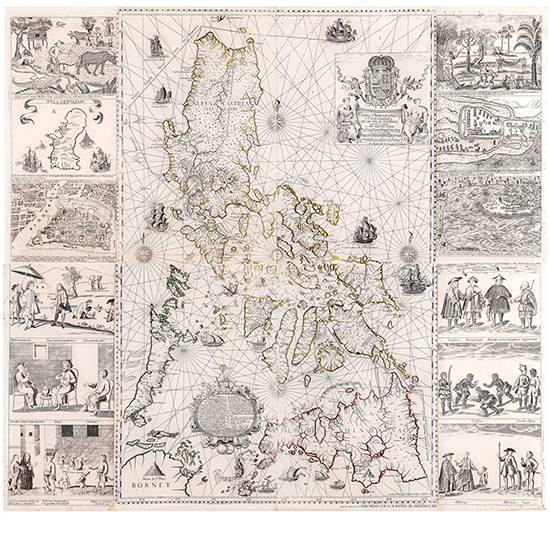

Juan de Salcedo, outnumbered from the onset, tried every trick in the book, short of armed attack, to persuade Limahong to leave the Philippines: threats, bribes (he promised to return the female slaves he had captured), and even an emissary with eloquent letters from Chinese ambassadors. Several centuries later, it would take the Philippines’ presentation of the Murillo-Velarde-Bagay Map of 1734 to prove in an international court that the West Philippine Sea belonged to this country.

In the end, Salcedo marshaled a special force composed of Manileños as well as men of Luzon to defeat Limahong. Astoundingly, he had managed to convince them to take the side of one foreign intruder against another.

There is a desolate painting titled La Derrota de Limahong (The Defeat of Limahong) in the Lopez Museum and Library Collection that, incidentally, has traveled for a once-in-a-lifetime exhibition of old masters at the University of the Philippines-Visayas museum in Iloilo City for the Dinagyang. Painted by Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo, it depicts the wily Limahong motionless but face-up, dressed in a combination of Chinese and Japanese armor, his identity masked by a horned helmet. Beside him are two pig-tailed companions, sprawled on the blood-drenched ground, also dead. Limahong is the only one defiantly holding a blade to the last.