One Life: The Power of One

In his inaugural address in 1961, president John F. Kennedy invoked God’s help and guidance, but ended his speech by reminding all, “that here on earth God’s work must truly be our own.”

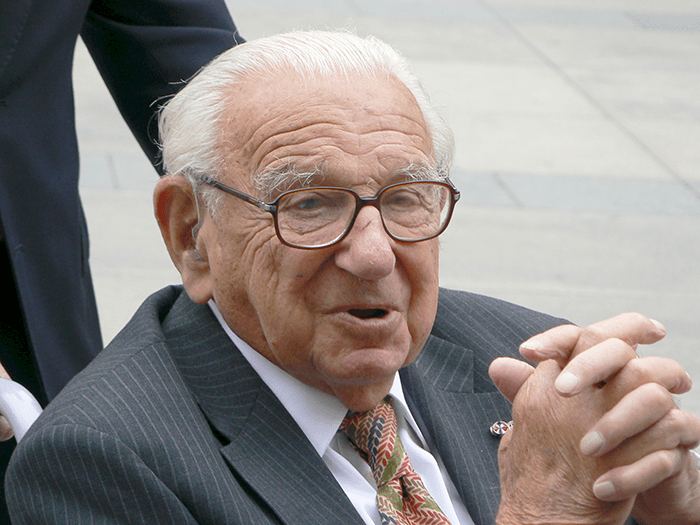

This quote came to mind after I watched One Life, a 2023 movie directed by James Hawes, starring Anthony Hopkins as stockbroker Nicholas Winton, who at 29 years old, successfully led an “army of the ordinary” to help 669 predominantly Jewish children flee Czechoslovakia before the beginning of World War II in 1938–39.

Winton has often been called “the British Schindler” and was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 2003 for “services to humanity, in saving Jewish children from Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia.”

Hopkins plays the older Winton in One Life, based on the book If It’s Not Impossible: The Life of Sir Nicholas Winton by his daughter Barbara Winton. The movie unfolds in 1987, as Winton reminisces about the Kindertransport, the heart-pounding exodus of children from Prague in trains for a new life in the United Kingdom just before World War II erupts.

Through the years after the war, Winton never tooted his horn about the children he helped save, till Elisabeth Maxwell, the wife of a newspaper tycoon Robert Maxwell, got wind of his story and shared it to the world through a newspaper article. The power of the press, indeed.

You have probably seen the YouTube clip of Winton, which was recreated in the movie, in the studio for the TV show That’s Life, where those in the audience who owed their lives to him were asked to stand up. When Winton looked around to see who would indeed stand up…. you have to watch the movie to see for yourself. No one? One? Twenty-one? Fifty-one?

***

Though Winton (the 29-year-old Winton is portrayed by Johnny Flynn) had solid support from his mother (Helena Bonham-Carter) and Prague-based British citizens like Doreen Warriner and Trevor Chadwick, he was the one who led the effort to take the Jewish children out of Prague after seeing their dismal conditions in squalid refugee camps.

In the movie, Winton gives a piece of a chocolate bar to one child, and out of the corners of the camp comes a multitude of children begging for their share till he had no more chocolate to give.

“I will bring more next time,” he promised. The next time, he didn’t bring chocolates—he sent visas to take them out of there.

Another truth the movie shows is that most good deeds require a lot of paperwork and legwork.

Winton discusses his plan with Trevor (who eventually lent him a leather briefcase for all the paperwork), Doreen and a Czechoslovakian named Hana while in a café in Prague.

Doreen was skeptical, indicating the task of bringing the children out was almost impossible.

“We have to believe this might be possible,” Winton asserted.

When it was suggested that their near impossible dream required a “lot of faith in the ordinary,” Winton countered, “I am ordinary.”

And both Trevor and Hana echoed him, leading the group to form “the army of the ordinary.”

It is true that the easiest to give is money. What Winton and his fellow humanitarians Trevor, Doreen and Hana did was to give their time and talent for organizing. Winton began by getting a list of endangered children (eventually all children were endangered) from a rabbi who was also skeptical about his (Winton’s) intentions but who eventually gave his trust to him.

Winton also enlisted the support of his mother Babette, whose parents were Jews but like Nicholas was baptized as a member of the Church of England, to secure the requirements for the visas. Imagine the queues she had to hurdle, the red tape she had to defy to let her son Nicholas know the requirements—including foster homes and 50 English pounds per child as guarantee for return expenses. Babette enabled her son to be a hero.

Originally, Winton and his army of the ordinary tried to get some 2,000 Jewish children out of Prague. Even in Prague, the children were refugees because they hailed from Nazi-occupied territories beyond it.

Working from home in London, and again, with the power of the press, mother and son completed the requirements needed for the visas. They sought and got the support of newspapers for their cause. They got the children’s photos published, galvanizing support for and attention to their plight. Lo and behold, families came forth offering to foster the children, and money came trickling in till it was a trickle no more.

And though thousands may not have been saved from Prague as Winton had hoped, each of the 669 children who were able to flee were given the opportunity for a new life, and make a difference in this world.

In the present day, Winton is shown meeting with his old friend and fellow humanitarian Martin (portrayed by Jonathan Pryce—people who watched the movie said it was like a reunion of the “Two Popes”)—wondering what to do with his briefcase of memories of 1938-1939. They reminisce. Winton tells Martin he feels he could have done more, and Martin tells him, “You save one life, you save the world.”

Indeed. Online sources said that as of the production of the movie, over 6,000, including the refugees’ eventual children and grandchildren, were alive because the original 669 had gotten out of Prague. Who’s to tell if one of those 6,000 had found cures for deadly diseases, or saved neighborhoods from fire, and lives in the emergency room?

One person not only can make a difference in this world. He or she is the difference.