Unraveling the tree rings of Yueh Faye Lai

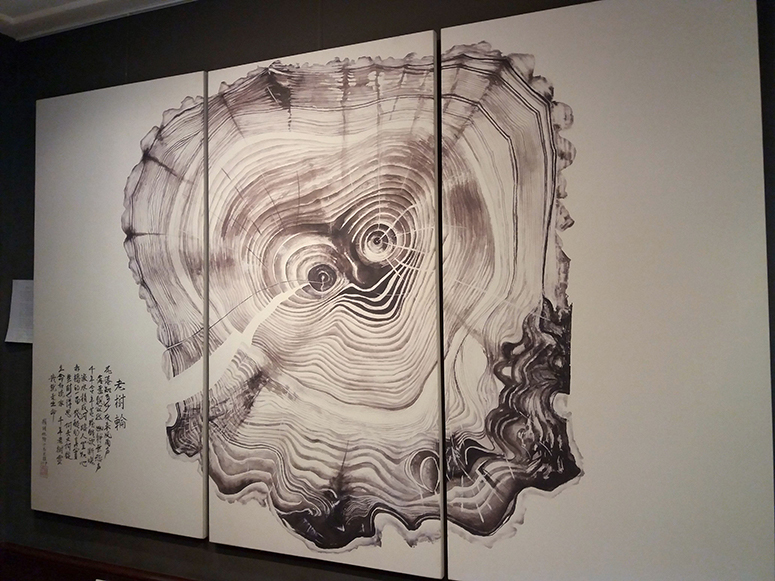

It took Yueh Faye Lai six months to paint a triptych called “A Thousand Year Old Tree.” Almost every time she lifted up a brush, she would call her daughter Nanette Medved-Po. “I would say my heart is so heavy. I’d cry so many times I couldn’t paint.”

While at the outset the concept is simple (a set of tree rings), the revelation is in the gesture. Ink is applied with different intensities: from the more deliberate and robust circles at the center; then, going outwards, hard lines dissolve into ribbonlike strokes.

The rings are habitually broken off by thin white spaces — like cracks in the trunk or, if we’re a little more playful, like crow’s feet in a woman’s eyes. In its incredible scale, the painting now hangs in Faye’s studio, a small room she disappears into during the long days of lockdown.

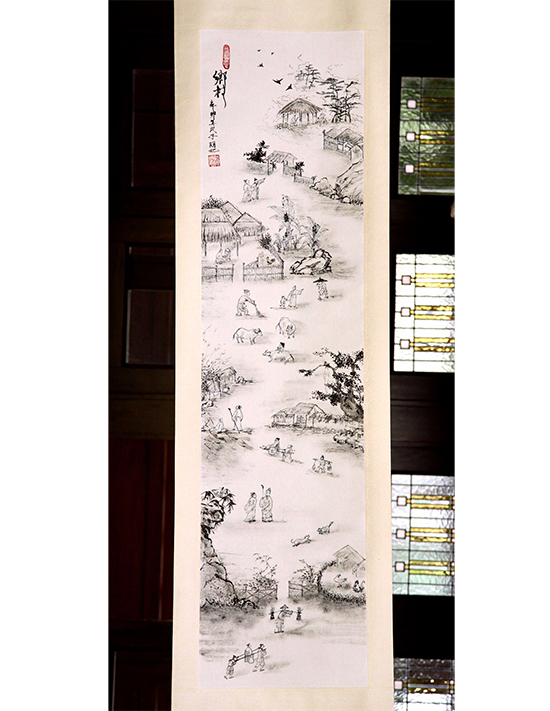

Now in her late seventies, Faye has turned to nature to work through complex emotions or for symbolic expression. She finds in mostly water-based mediums a way to inscribe flux.

In another painting called “Wilted Leaves,” ink and paint bleed through one another to evoke her humble subject’s curled contours. Gesture calls up the animate in matter, and through it we sense something invisible moving through, maybe wind or maybe time.

We did it for leisure, to kill loneliness, Yueh Faye Lai confides. They paint to pass the time or, perhaps, to make peace with its passage.

“I was brought up in a culture of Taoism and Buddhism environment in Taiwan,” says Faye, “and (Confucian) philosophy’s morality and discipline.” She says these Eastern thoughts and sensibilities — “the Taoist love of nature and the Buddhist principle of emptiness” — still prompt her to find what she refers to as the eternal expression in every scene.

But of course, it isn’t always easy to find it. Nanette and I walked around the room, from painting to painting, noting down the commonalities. Next to the works were a page of bond paper, where Faye had translated her poems precisely for this visit.

She works within the tradition of Chinese painting that is inscribed with poetry, where image is fulfilled by language and heightened by calligraphic brushwork. Sadly, neither Nanette nor I could read Chinese.

“I’m reading this for the first time!” said Nanette as she recited her mother’s words on “A Thousand Year Old Tree.”

This same struggle with translation would mark our interview the week after. I met with Faye on Zoom, her first time using the platform, and asked the more general questions about her work.

While at times we circled back and forth, trying to understand each other through the divide, she was always warm and patient. I asked about subject matter, and she responded with insights on calligraphy. Later, when we talked about her poems, she recounted how difficult it was to translate them in English.

This bout with remembering, finding the right words, or adjusting to someone else’s language wasn’t new, but one she had to contend with for most of her life.

Growing up in Taiwan, Faye discovered what many would assume was a natural talent in painting — in fifth grade, she won a national competition for a sunset scene in watercolor — but she had to set the hobby quickly aside.

At 24, when her marriage ended, she moved to the United States to make a living as a real estate agent. “I worked so hard to survive by myself,” she says. These tumultuous years of adjustment were likely what she recalled when painting the tree rings.

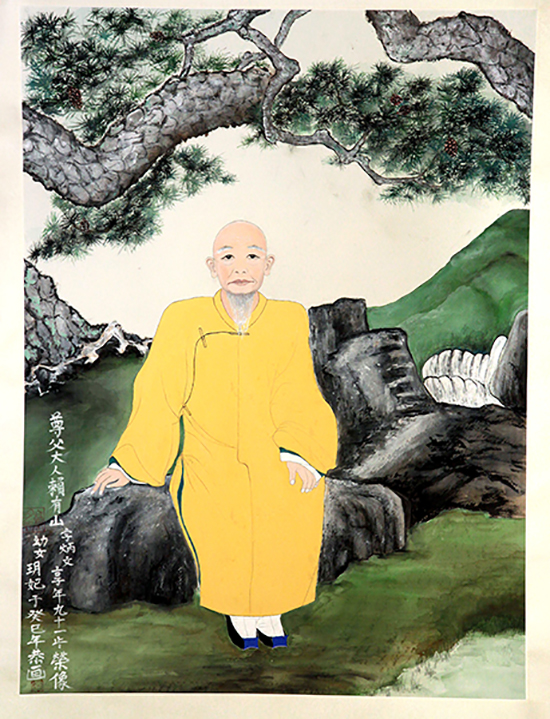

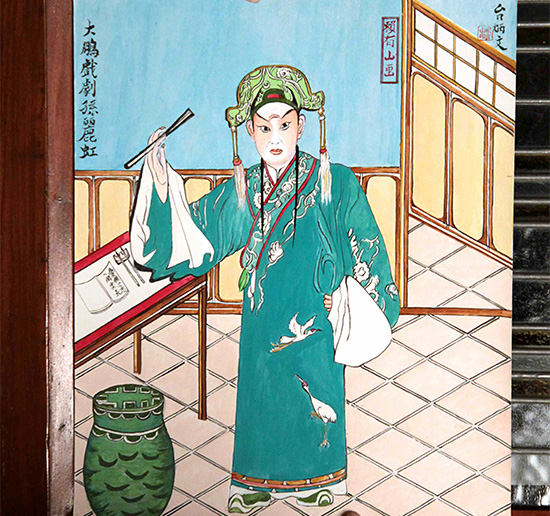

It’s tempting to make out the similarities between Faye and her father Lai You Sun, who did not pursue art until much later in life.

When her mother passed away, he came to spend the rest of his years with Faye in Oakland California. “He had no friends, he did not speak English, there was no Chinese-speaking community nearby,” she recalls.

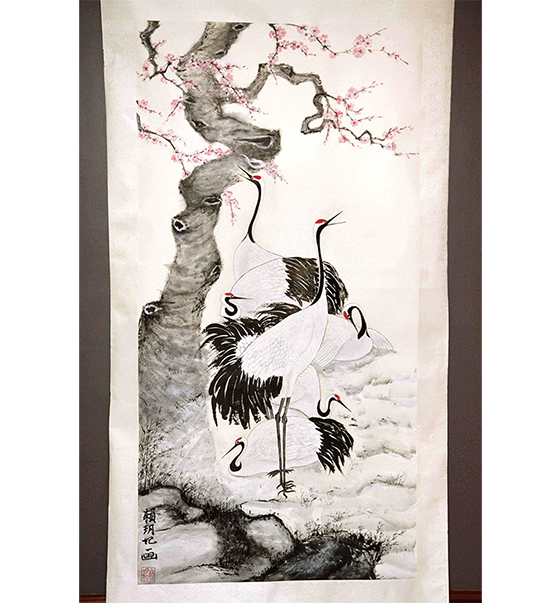

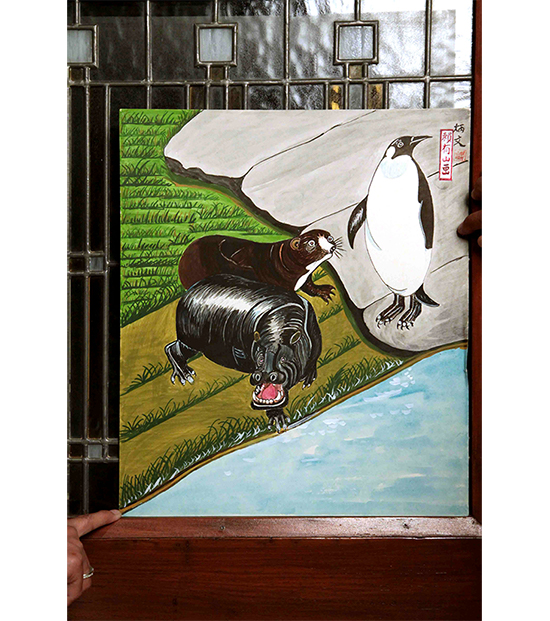

In isolation, he found constant companions in paint and brush. Faye describes her father’s style as “more Western,” a self-taught artist striving for accuracy in shapes and shadows.

His scenes, however, were of life in Asia: the Japanese gardens, water pavilions, Chinese folk heroes, rendered with studious attention paid to filling the entire composition.

There’s playfulness in his patterns and in his childlike love for bright blocks of color held together by lines. But as in his portrait of his wife Lai Zhau Mei, there is somberness too, revealing affection. “He painted his wife to remember her,” says Nanette.

Faye’s technique may be different — having trained with masters Chen Pin Sun and Zhang Ching Zung — but perhaps what she shares with her father is some longing to reconnect.

“We did it for leisure, to kill loneliness,” she confides. They paint to pass the time or, perhaps, to make peace with its passage. When she moved to the Philippines 12 years ago to be with her daughter, Nanette encouraged her to paint again.

While a 2015 show at the Yuchengco Museum was the first — and so far, the only time — she’s exhibited their works publicly, she is satisfied with having her family as the only audience. When not in the studio, she’s possibly spending time in the garden, trying to see which leaves to keep from the gardeners’ lot.

Asked why she always picked out the dried ones, she answered, “They are dead, twisted, wounded, wrinkled, but I discovered in each leaf individual characteristics: the way they dried, the forms, the shapes. It’s like a landscape. It’s a life.”

Banner photo courtesy of Nanette Medved-Po