Streets of Rage: An interview with Filipino crime novelist Ronaldo Vivo Jr.

The local indie presses are replete with talent and skill. It’s also true that they often go unnoticed, past the radar of critics and mainstream outlets chasing the popularity of the next news cycle.

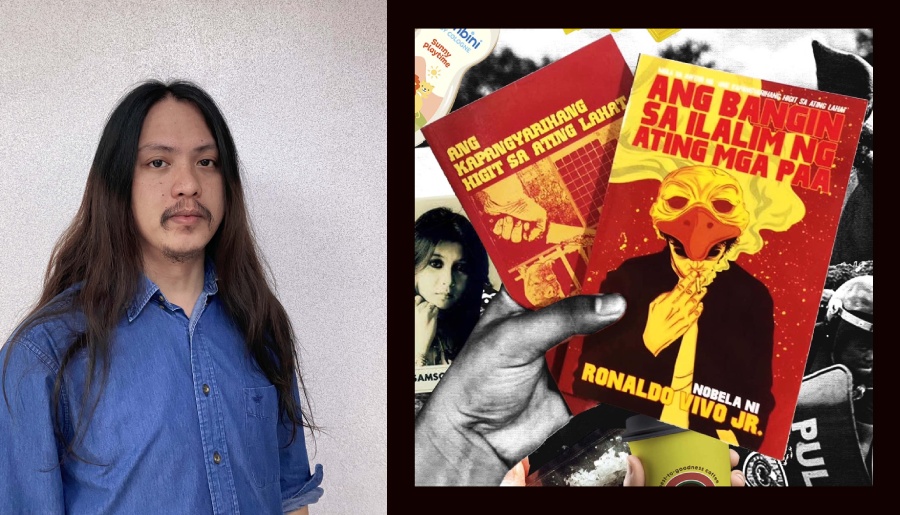

So when a writer like Ronaldo Vivo Jr. bursts forth from the fringe to achieve cult status, beyond the bubble of academic press coteries, writing workshops, and established publishing systems, the literary pool is vastly enriched. It may seem that he’s suddenly been discovered, yet he’s been honing his dystopian stories for years.

Vivo is the author of two books in Filipino, crime novels that are not for the faint of heart. Books as sharp as the authentic Filipino inner city vernacular he thrives in. His name may be familiar to those in the Filipino metal scene. Vivo’s the drummer of some extreme music supergroups, like the sludge metal project Dagtum to his current doom outfit Basalt Shrine with members of Surrogate Prey. He’s also a feted filmmaker, his short films constantly on the international film festival circuit. Ritmo ng Palahaw his most recent outing made it to the US South by Southeast Asia x Seattle Film Festival.

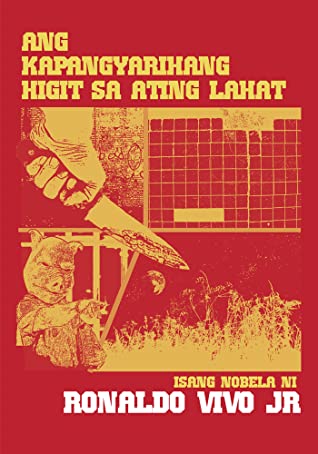

His first novel is Ang Kapangyarihang Higit sa Ating Lahat (2019, Psicom Literati). The Power Above Us All was a finalist at the Madrigal Gonzalez First Book Award. A shambolic collection of intersecting stories about criminal misfits and power drunk police that aren’t so much a cohesive narrative as a means to put forth a message about the reality of a hardscrabble life, specifically the shanties and slums known as Dreamland.

This debut is like an extended writing exercise on how to marry procedural mystery and reportage of inner city life. Characters like the streetwise Dodong and his best friend Buldan, the golden hearted prostitute Che, and the odious Elmer are like experiments to see how far one can stretch narrative realism without wading too much into gratuity. Here, Vivo took his roots from forays with his friends into zine-making to a literary level of practice, to the point where he could comfortably fire on all cylinders, beyond the noir and transgressive influences he had grown up with.

Reading it, you get a sense that this is more about making a point, proving that the author did have the stamina to accomplish a novel-length story. Vivo copped to this readily enough. “I just really wanted to prove to myself that I could write a novel that time. I can see now how it works and not work in the rearview of my second novel, I mean it looks pretty crude to me now.”

In Kapangyarihan there’s a Metro Manila that’s only reported in the city pages of newspapers and glimpsed at in headlines. To folks who wake up every day to that reality, it’s just another day in perdition. The people in his stories don’t so much live as suffer in degrees of hell. A life under constant poverty and state oppression, occasional sparks of hope lighting up their firmament between birth and demise.

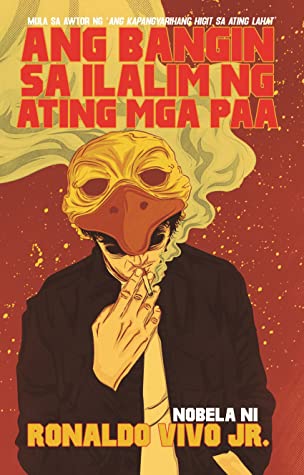

His second book Ang Bangin Sa Ilalim ng Ating mga Paa (2021, Ungaz Press) is where his storytelling powers made a leap from scrappy wordsmithing to pugilistic literateur. Though he credits The Abyss Beneath Our Feet, like many creative projects during this time, to suddenly possessing a huge blocks of days due to COVID quarantine, his pacing and plot twists are like a high intensity car chase turning on narrow alleys. Here, his ear for underground language takes us past street level into the sunless bowels of graffitoed walls and rat-infested corners.

Bangin is nominally held together by the story of a search for a missing person. Reynold Ventura has set out to look for his lost his teenage daughter, Alison, who has mysteriously never come home. Distraught and fearing the worst, Rey enlists his buddy Benjo in the hunt and through the process we are treated to a descent into the titular abyss of Philippine despair.

Sometimes books are also a repudiation of everything wrong with our social and political systems. This one is about the past six years: the ills brought on by the Duterte drug war, the EJKs, the rise to fore of police and state-sanctioned oppression, the further dearth of justice for the poor, and the rising popularity of fake news.

His novels depict a Metro Manila in the claws of both neon and darkness—that have either become too romanticized or given an exaggerated makeover for poverty porn purposes in film and literature.

Both his novels are set in the inner city “ghetto” of Dreamland and similar environs. Places where corrupt police control neighborhoods like medieval warlords, small-time dealers and prostitutes cling to each other in hopes of escaping their fate, and petty theft dovetails with a daily dose of meth or speedball to supplement the meager nutrition of one’s meals.

None of his heroes are pure. Nobody is without sin in Vivo’s novels. If you have lived in the slums, you can hear the argument and brag ring clear on Vivo’s streets and out of the nicotine-stained mouths of the protagonists. His novels depict a Metro Manila in the claws of both neon and darkness—that have either become too romanticized or given an exaggerated makeover for poverty porn purposes in film and literature—are here presented sans agenda or hyperbole.

Here too, sans much filter, is an exclusive interview with the novelist.

***

There’s a pretty big compositional gap between “Kapangyarihan” and “Bangin” that it almost seems like two different authors wrote it.

The second novel was really a product of being in COVID lockdown prison. I had plenty of time to write but yeah there was a six-year gap between books. If there wasn’t a pandemic I wouldn’t be able to have that much time to write but it was also definitely a time of frustration with the government.

I don’t think I could do this again without such a big block of time and all that momentum. I was already conceptualizing it by the third quarter of 2020, outlining and working on a draft, and then by February 2021 I had finished the novel’s first draft. I did remove plenty afterwards to cut out the fat but that was really quite fast writing for me.

My target reader is always someone who doesn’t read. And the best feedback was from those young people who said they don’t really read but said this book works for them.

Is Rey Ventura, your hero in “Bangin” a biographical extension of you, being a father yourself, and both having the same initials?

I named him after the actor Rey Ventura, the actor who is a contemporary of Joel Torre and Nonie Buencamino in the '90s. An uncle on my mother’s side is in construction and that’s where I got the hardware store references and quirks of the industry worker.

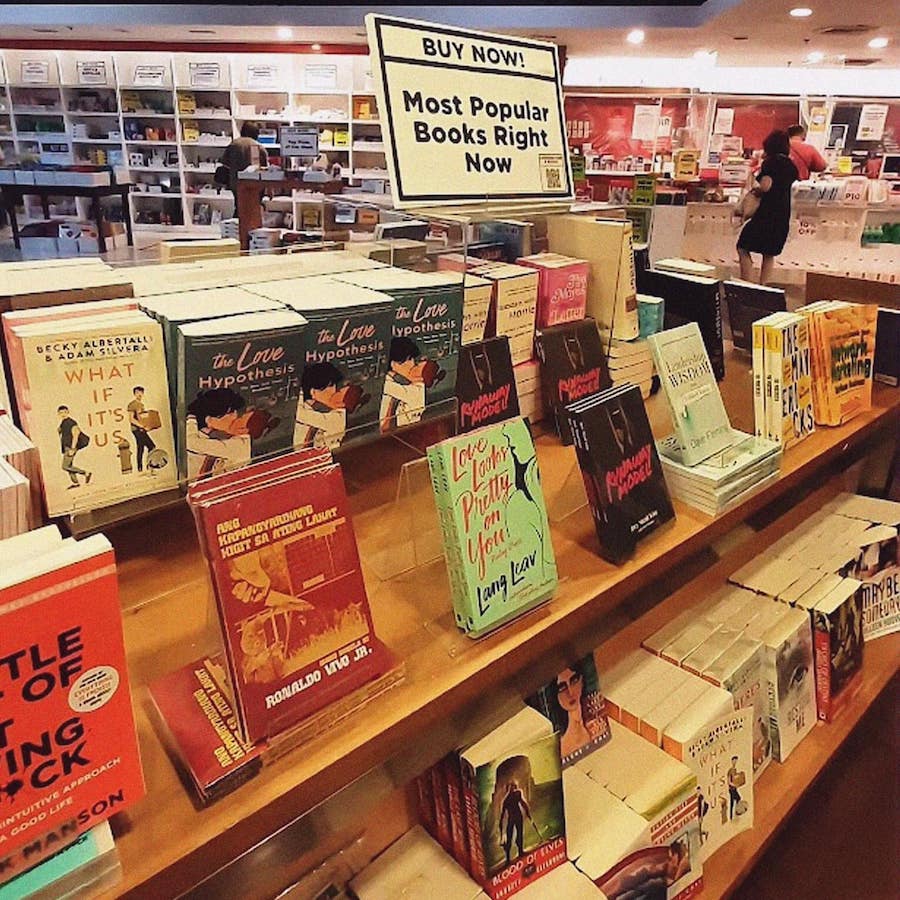

Your novels ring like fictionalized yet easily plausible stories from the Loobans of the Philippines without pretense or exaggeration. Especially in the first book, “Kapangyarihan” which became a cult hit that it got picked up and re-printed by Psicom from its 2016 original pressing.

In Kapangyarihan that ear for the authentic was a product of long time practice. It goes back to Ungaz Press in Pateros, my high school friends, a community writing group where we just wanted to put out stuff that we liked as a zine, back in 2012. I’d collect the handwritten stories and notes and poems and I said, one day we’ll put these all out to be published.

Then I bought a printer and (of course!) a drum set with my first paycheck. We did it zine style, learning how to print, design, produce. Seven of us assembled our first issue with short stories and we put out 100 copies. We sold it at school fairs and mini bookstores. We sold out!

What I picked up from those times was that the language and relatability of how characters speak in certain locations is very attractive to readers. Even the stutter of the characters I’d incorporate them. I never wanted the people to speak in long and rehearsed lines apt to novels. They should talk like they would in casual conversation. Make it crispy and sharp! I applied what I learned from zine writing. That’s how I nurtured the values of that time into my novels. The language in Kapangyarihan was a direct line from those days.

So language and authenticity, the registers and spirit of each place, are important to you because their presence imposes so much on the characters?

To the kids who read their feedback was the novel was like the first time they stepped foot in the Looban! That’s why they liked it.

I’d always ask myself what can I contribute to the current milieu? My own review of related literature was looking at the current books that were similar. My realization halfway through the material was that my main contribution and how to stand out was to get the language right. Get the mannerisms and the culture of the setting right. That’s how it’ll be unique beside the other Tagalog novels that would be released or have been released recently.

How to make it catch fire? Flesh all those out. I should get the nuances, pauses, and emphases right. Biggest thing I took to the extreme from the first to the second book. Same thing with community music. Salbakuta would never come out of Alabang.

This is a technique that seems to have been lost to many novelists who want to work in the vernacular of our literature.

Plenty of Tagalog writers are great at describing things. I mean they’re great technically with description. But they usually can’t get the details of the culture, especially the underground culture, just right.

For example, many books describe a drug deal where a character is buying “epektos.” If you’re from the Looban like me, you don’t call drugs “epektos”! If you’re buying, you won’t even say that. Authenticity is key for me. The readers need to hear familiar things happening in a scene so they can feel grounded.

See different places have different registers, even if they’re all in Metro Manila. There is a different point in Pateros. Different in Las Pinas. Different in Valenzuela. The ghetto of Makati is not the ghetto of Caloocan. You don’t have a firm grasp of a certain locality? It will sound… off. It’s important for a novelist or a writer to know those and have the technical ability to put it on the page if you want to depict scenes in a crime novel in a certain setting.

Tiktok, Facebook, IG, all those are fast consumption platforms. How can I get to those people who don’t read books but do write and read on those? Just seconds allotted to capture interest. How to do that in a novel?

Aside from that, you take pains to have things entertaining and always move thing along at a pace.

My target reader is always someone who doesn’t read. And the best feedback was from those young people who said they don’t really read but said this book works for them.

Make it as lean as possible so the patience of the reader is not tested as much as possible. It’s always left hanging to provide chapter by chapter momentum. My habit is to make every chapter as much as possible stand alone. A short short minimalist per chapter that’s not necessarily linear.

I always thought about the time of reading. Tiktok, Facebook, IG, all those are fast consumption platforms. How can I get to those people who don’t read books but do write and read on those? Just seconds allotted to capture interest. How to do that in a novel? So I structured it like it was streaming, like a Netflix episodic series.

With such extreme and intense scenes in your stories, is writing something that is fun or pleasurable for you?

Writing is never fun. If there was a machine that could execute on to the page what was in my head, then I’d buy that right away. No matter how expensive it is, I’ll buy it!

When people post about how writing and how it’s their channel, their outlet, their valve to let off steam, their way to breathe my reaction is always: wow, these guys are on another level huh!

Creative constipation is a constant. What’s enjoyable is finishing. Edits. Not even revisions. The process of revision is always just a bit less of a pain than actual writing.

So why write, people ask? I am compelled. Who else is going to write these stories how I will? Someone else might miss the details that I see. The kids who ask me in interviews always react weirdly: bakit daw po ba mahirap mag sulat.

And sometimes the whole writing process is also discovering you can’t write for that day. You feel like you can, when you’re walking down the street. Then you sit down and pak, nothing. Nothing for six hours! And then you say well, okay we aren’t ready then. That is also considered writing.

Order the books or connect with the author at https://www.facebook.com/ronaldovivojr