The living sound in translations

When Marne Kilates departed in July 2024, we lost not only a premier poet in English, but a top-rate translator into Filipino. His proficiency as a translator (from both Bikol and English) was such that his most significant works in recent decades were almost exclusively devoted to the poetry in Filipino of National Artist Virgilio S. Almario a.k.a. Rio Alma, with whom he shared mutual appreciation of their respective literary merits.

Almario hailed Kilates as “a vital, creative and patriotic literary voice,” while Kilates viewed his translation work as “a journey alongside Almario’s literary vision.”

Their collaboration spanned several decades, resulting in such significant volumes as the senior poet’s exceptional “exploration of Filipino identity and history”—Pitong Bundok ng Haraya (Seven Mountains of the Imagination).” Other works that rewarded English readers with the treasures of Tagalog literature included the bilingual anthology Selected Poems 1968-1985; the poignant poetry collection Lemlúnay (where the translator’s note stressed its importance “in redefining Filipino self-pride”; and Pitik-Bulag: An Art & Poetry Coffee Table Book, co-edited and translated by Kilates, featuring works by Filipino artists and poets, including Almario.

With the unfortunate end to their partnership, Almario had to find someone else with the literary wherewithal to share his core concerns as a National Artist. It came at a point when he had just completed a new collection. Thankfully, he couldn’t have done any better with his choice.

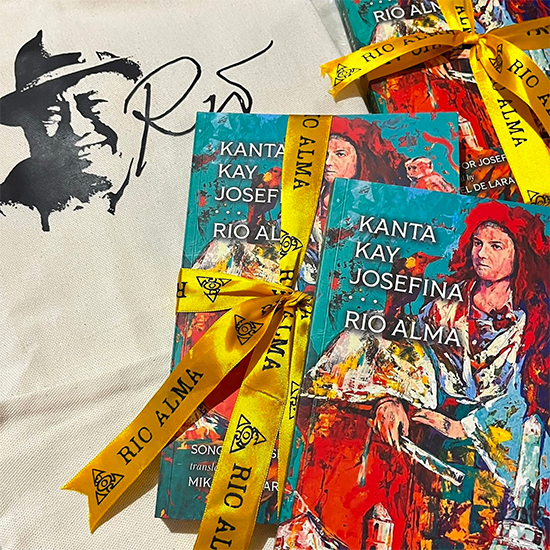

Launched in time for Quezon City Day on Aug. 19, 2025 at the Ferndale Village Clubhouse as part of Pista ng Sining sa Ferndale was Kanta kay Josefina (Song for Josefina) by Rio Alma, translated by Mikael de Lara Co, published by the NCCA. The splendid painting used for the cover, plus inside artworks, are credited to the collectors’ artist Celeste Lecaroz-Aceron.

At only 42, bilingual poet Mikael de Lara Co earned his spurs early. His own poetry books and translations were finalists for the National Book Award four times. He won the Maningning Miclat Award for poetry twice. And supremely, has won the Palanca Awards’ first prize for poetry five times, elevating him as a Hall of Famer in 2024. There were consecutive years when he won the first prize for poetry in English thence Filipino.

Among his published titles and award-winning poetry collections are: What Passes for Answers, published by the Ateneo de Manila University Press in 2013; Canopy, published as part of the deciBels series by Vagabond Press in 2017; Panayam sa Abo and Epistolaryo ng Bagamundo at ang Tugon ng Multo—collections that won the Palanca First Prize for the Tula category in 2023 and 2024. His individual poems and translations have been anthologized in prestigious journals such as Cordite Poetry Review, Four Way Review, and Likhaan.

In his preliminary reflection as translator for Kanta kay Josefina, Kael recalls a conversation he had with his fellow “poet and translator (and later on godfather) Michael M. Coroza,” more senior and wiser, who had said: “‘Ang translation, parang beast transplant. Kailangang Mabuhay.’ Translation is like a heart transplant—the poem must live. The transfer is never just technical: the sinews of language are threaded now for display or as an exhibition of mechanical fidelity, but to achieve that singular goal of generating pulse, breath, feeling.”

Given an increasingly tight timetable and other obligations, Kael had to struggle to gain momentum as he started to work on Almario’s hundred or so original poems. This involved a “return to earlier drafts, tweakings and reworkings, occasional consultations with Sir Rio via FB messenger…” The full draft was achieved “after a short back and forth with Sir Rio, who had given me further notes on intent and on nuances I had missed.”

Most of the poems are from recent years and the past decade, except for Sa Wikang Griego from 1986. Here’s one of the briefer poems:

“Oyayi ng Relo”: “Saan napupunta ang mga tanong ng musmos?/ Sa tuktok ng bundok./ Sa pusod ng dagat./ Kailan masasagot ang mga tanong ng musmos?/ Pag nakalbo ang bundok./ Pag nabaog ang dagat./ ‘Malapit na,’ ang ugoy ng laboratoryo./ ‘Binabalakubak na ang bundok.’/ ‘Oo, malapit na,’ ang bulong ng pabrika. ‘Ginagalit na ang dagat.’”

“Timepiece Lullaby”: “Where do the child’s questions go?/ To the mountaintop./ To the navel of the sea./ When will the child’s questions be answered?/ When the mountains are stripped./ When the seas go barren./ ‘Soon,’ the laboratory sways;/ ‘Scurf is already forming on the mountains’/ ‘Yes, soon,’ whispers the factory./ ‘The sea is already breaking out with sores.’”

The bilingual collection has four thematic parts: “Obertura sa Naglalaho at Ginugunita (Overture to the Vanishing and the Remembered)”; “Parinig at Parunggit (Allusions and Innuendoes)”; “Pagtawag ng Simoy (Summoning the Breeze)”; and “Mga Layak ng Mundo (World’s Debris).”

To be sure, a challenge for any translator of Almario’s poetry is to avoid simple reliance on its inherent primacy, which could be enough to lend strength to an interpretation in any language.

De Lara Co writes: “I’ve long learned that translation is less a process of solving than it is of listening—of allowing oneself to become porous in another consciousness, another heart. I offer these translations, after having listened as intently and as deeply as I could, with gratitude and a certain trembling. I doubt it is perfect, but it was done with care, and with love and reverence not only for poetry but for the man who wrote them. I can only hope that something of the original remains intact, and that, in these English versions, the reader hears an echo, hopefully a living sound.”

Here’s an excerpt from the last, longish poem, the finishing lines in the final stanza of Ang Pagtula ay Kaaway ng Kapayapaan (Poetry is the Enemy of Peace):

“Ang pagtula, kahit paano, ay naghahandog ng liwanag/ Sa mga lihim na pinagkakaitan ng pagkakataong maipahayag,/ Sa mga hiyas na dapat pang itanghal at ipatuklas./ At kung hindi, ang pagtula ay nararapat lang isadlak/ Sa basurahan ng mga nakamishanang katitikan at opisyal na ulat,/ At ng mga de-kahon at gasgas na tugma’t sukat,/ At ng mga de-susing bangis ng kamao at pulang watawat.”

“Then poetry, at least, offers light/ To secrets denied a chance at declaration,/ Treasures that should be displayed and discovered;/ And if not, it is only right for poetry to be cast/ Upon trash bins filled with staid letters and official reports,/ And dogmatic, worn-out rhymes and meters,/ And the mechanical brutality of fists and red flags.”