Driven to Abstraction

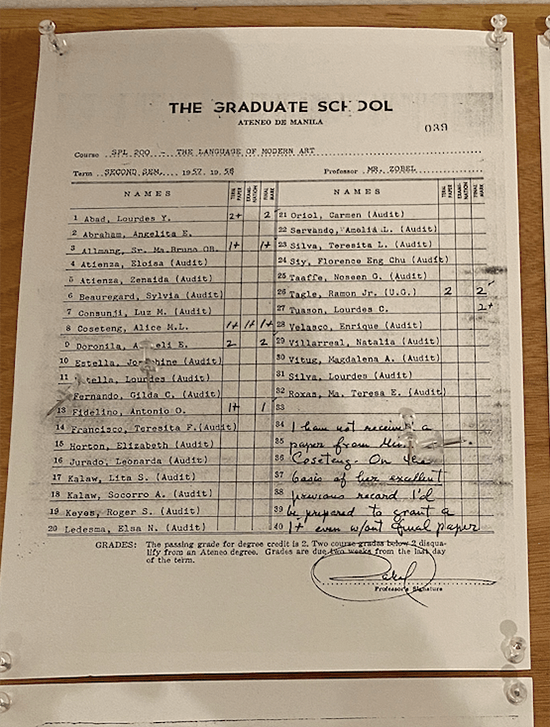

One thing you notice upon entering “A Synergy of Ventures,” the exhibit of works donated by Fernando Zóbel to the Ateneo between 1959 and 1981: there’s a display of grade books from the graduate class he taught there in 1957 (“The Language of Modern Art”). Some of the familiar names that audited the class—including Gilda Fernando, Lita and Socorro Kalaw, Alice Coseteng, Tessie Ojeda, Teresa Colayco, Don Jaime de Ayala and artist-students who came up under the guidance of Zóbel—read like a who’s who of the social and art circles of the time.

“You’ll probably recognize some names… Some of them didn’t submit requirements,” laughs exhibit curator Victoria “Boots” Herrera. She debated whether to include this bit of ephemera in the show, along with a course outline, but she’s glad she did: visitors were already poring over the list of soon-to-be-famous students, along with several of the artist’s travel sketchbooks and personal items. The grade books add to fleshing out Zóbel’s influence on his generation, and a whole era of Filipino art that was about to unfold after WWII.

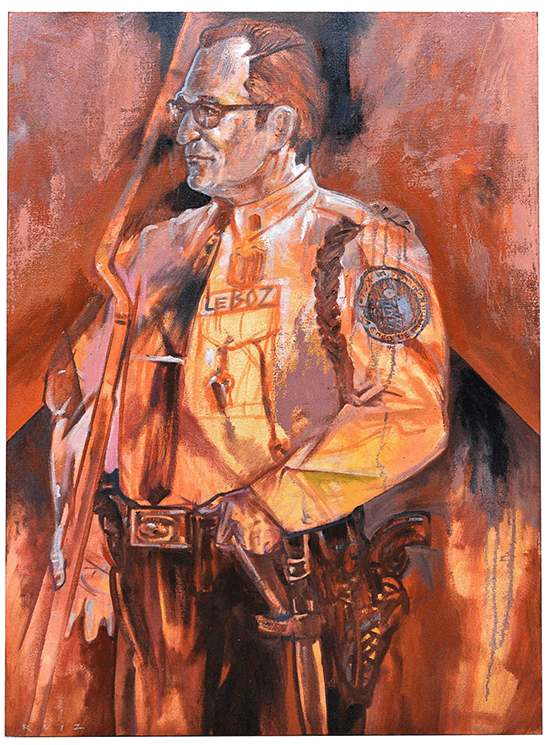

Another striking work greets visitors at the entrance—an oil portrait of the handsome young Zóbel in 1920, done by Fernando Amorsolo, no doubt a commission by (or a gift from) the great Filipino artist who’d been sent to study further in Madrid by Enrique Zóbel de Ayala.

You get the sense of the torch being passed in “A Synergy of Ventures,” running at Ateneo Art Gallery until July 12, 2025. A host of high-powered guests (including Fernando Zóbel II and wife Kitkat, trustees of the Purita-Kalaw Foundation, Spanish Ambassador to the Philippines Miguel Ultray, and others) came for the launch event, in which we learned, according to Spanish Ambassador to the Philippines Miguel Ultray, that there are streets and even a high-speed train station named after Zóbel in the city of Cuenca, Spain, where the artist founded the Museo de Arte Abstracto Español at Casa Colgadas in 1963. Amb. Ultray was at the launch of two big Zóbel exhibits that September week: “Zóbel: The Future of the Past” had just opened at the Ayala Museum, while the Ateneo Art Gallery show opened the following Sunday. Said Ultray, “His relevance is not limited to the Philippines, but spans Europe, America (as well as Asia). Fernando Zóbel was, and is, a true bridge between the three continents.”

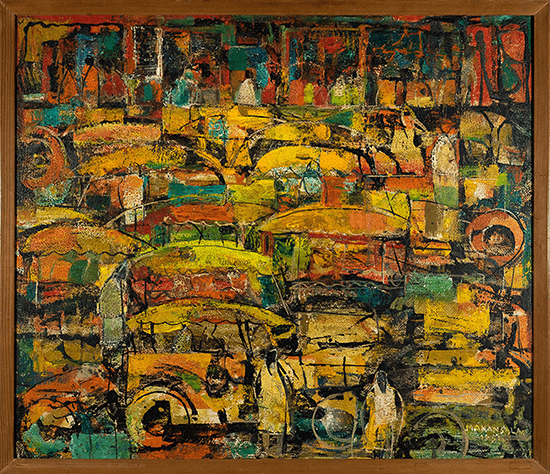

A walkthrough showcases the budding Manila art scene from the 1950s onward: there’s a striking, small Anita Magsaysay-Ho panel of three women holding back a contagious titter (“Laugh”) that has been on the walls of the Purita Kalaw-Ledesma family home for decades, says Ada Ledesma-Mabilangan, Kalaw-Ledesma Foundation trustee. (Boots says it’s her favorite.) You’ll see Hernando Ruiz Ocampos, early works by Lee Aguinaldo, Jose Luis Balguero, Romeo Tabuena, Vicente Manansala, Victor Oteyza, and a room-length yellow abstraction by Jose Joya (“Granadean Arabesque”) that leaves you absorbing its impact for several minutes.

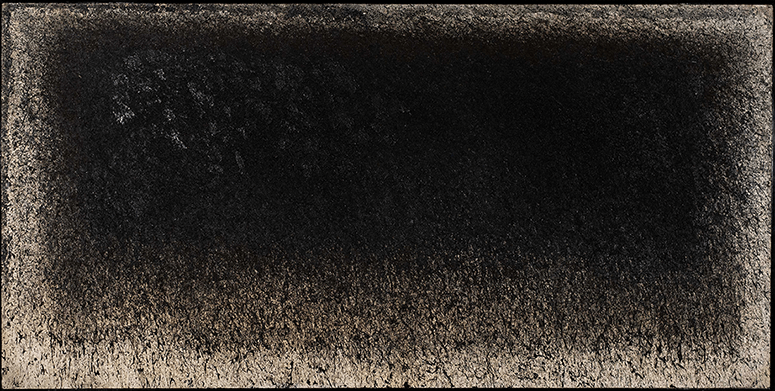

Importantly, you’ll also see the shift in the style of Zóbel and his fellow Filipino artists, shortly after Fernando studied in the US, where he encountered Abstract Expressionism for the first time. Before this, Zóbel was entrenched in the figurative Filipino art scene of the era — an embrace of neo-realism that often depicted Filipinos toiling at labor—before studying in New York, where he encountered, among others, the abstractions of Rothko and Jackson Pollock. It rocked his world. Line was still fundamental, and Zóbel took to using a syringe to “inject” lines onto his ever-larger abstract canvases. (“I saw a cook writing ‘Happy Birthday’ in icing on a cake… I wondered why it took me so long to figure that out…”) The “Saeta” series represented here is an indicator of how far the artist would go in capturing that “internal” emotion and (literally) spray it on the canvas, but he was to go much further.

Was it the CIA-funded Congress for Cultural Freedom—which some Filipinos suspect was used as a tool to steer artists towards abstraction and away from “political” representational art—that led Zóbel and other artists to embrace the vague and subtle shapes that took over the art scene in Manila? That is a topic for another day. Clearly, Zóbel and others saw in abstraction a new pathway to Filipino expression. “The first attempts of modern painting, the not always well-understood copies of foreign styles, are soon forgotten, and a kind of native expressionism emerges,” writes the artist, speaking of a new era in the ‘50s. “The houses destroyed by the Japanese are now in full reconstruction, and their walls, simple and modern, need life, which can only give good paintings. The exhibitions are full. These artists, and so many others—what do I know—represent a rebirth, or rather, the true birth of a national style.”

I bump into ArtFairPH co-founder Trickie Lopa, who recalls seeing so many of these paintings displayed all over campus and in certain Manila homes over the years; to see them all in one linear journey was Herrera’s intent: “This is the first time we are exhibiting a substantial portion of the Zóbel donation, and the exhibit gives us the chance to view post-war Filipino art through the lens of Fernando Zóbel as an artist and as an art patron.”

The show’s title is a reference to a 2019 essay by Eileen Legaspi-Ramirez, in which she outlines the importance of women in Southeast Asian art. Fittingly, as it was Purita Kalaw-Ledesma, founder of the Art Association of the Philippines in 1948, and Lydia Arguilla, who co-founded the Philippine Art Gallery in 1954, who helped usher in a postwar environment where art, criticism and exhibition could take hold and flourish. Other gallerists—Manuel Rodriguez Sr., Arturo Luz—would follow.

* * *

“A Synergy of Ventures: The Post-War Art Scene” runs at Mr. and Mrs. Ching Tan Gallery and Mr. and Mrs. Chung Te Gallery, UGF, Ateneo Art Gallery until July 12, 2025.