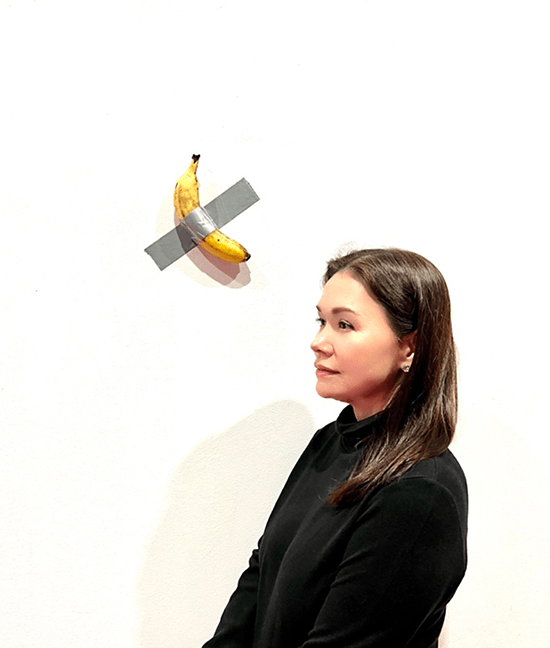

That iconic banana and the Maurizio Cattelan exhibit

“Comedian” created quite a stir. In 2019, satiric artist Maurizio Cattelan stuck a 30-cent banana on a wall with duct tape at Art Basel Miami Beach. It sold for a whopping $120,000. The banana and strip of duct tape came with a certificate of authenticity, with detailed instructions on how to display it.

The art world was abuzz. How did its price justify this “conceptual art”? What did it mean? Just bananas, right?

In a way, it was not surprising for a work from Cattelan, known as the “outsider of the art world,” who has a dark sense of humor. There is, of course, his famous solid-gold toilet called “America; L.O.V.E.” or “Il Dito,” that huge hand monument located in Milan, with a middle finger up and severed digits; “La Nona Ora,” a sculpture of a pope being hit by a meteorite; and of course, his taxidermied animals.

The controversial works of Cattelan are currently on exhibit at the Leeum Museum in Seoul until July 16. The exhibit, titled “WE,” is the largest display of the provocative artist’s works since his 2011 retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. It is a must-see, or shall I say, must-experience. Three floors have been dedicated to show 38 works from three decades, since his emergence in the 1990s.

As you walk into the museum space, you see a life-size hanging horse called “Novecento” (meaning 1900s but referring to the 20th century). The horse usually represents war heroes, power, and nobility, but this horse dangling from the ceiling looks pitiful, droopy, surrendering to the pull of gravity.

Unveiled in 1997, “Novecento” also refers to Bernardo Bertolucci’s film depicting the rise and fall of fascism in Italy during the two World Wars. The force carrying the horse upward and then downward is a serious warning of the aftermath of war.

Two hyper-realistic men lying on a bed is displayed a few feet from the hanging horse. The effigies resemble Cattelan himself. They look like twins or clones, and invite us to think of our own “contradictions and conflicts.”

The double self-portrait is a statement on “life, death and authority; it’s both an homage and subversion.” It references a photograph produced by Spanish playwright Federico Garcia Lorca called “In Bed with Lorca,” by Gilbert & George in 2007. Fascists assassinated the writer for being gay and a socialist. With this work, Cattelan shows his support for those considered “outsiders” like him.

An eerie but strangely hopeful sight is a pair of worn combat boots with soil and plants growing in it (“Untitled 2008”). Apparently, there are multiple meanings for this piece. It was first shown in a historical synagogue building, which was to be demolished under the Nazi regime but was spared because a farmer smartly converted it into a barn. So the artwork symbolizes hope, survival, and renewal.

Another meaning is that boots represent the “heart of the pilgrim who perceives the sublime in humble daily objects.” Cattelan’s ownerless boots depict the “nuances of everyday life, arduous labor, and even death, yet remind us of the continuous cycle of life.”

Out of the museum’s floor, a man is sticking his head out, also looking like Cattelan himself (“Untitled 2001”). The man is probably a thief, or maybe just some guy who excavated a tunnel and ended up in the wrong place. This work first came out in Rotterdam’s Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum surrounded by paintings of 18th-century Dutch masters, as if the Cattelan lookalike was out to steal these priceless pieces.

But then again, in the 1958 film I Soliti Ignoti, the main character embarrassingly ends up in an apartment but was originally planning to build a tunnel to a pawnshop. There’s a bit of comedy to it. I was amazed that the Leeum Museum actually deeply excavated through their cement floor for this piece. The result of this destruction, though, is worth it.

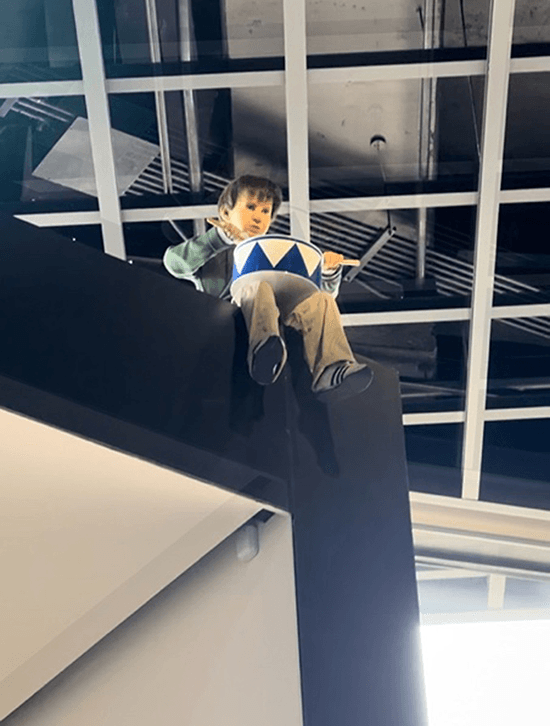

There’s a bit of “performance art” in the WE exhibit, too, if you can call it that. Out of the blue, you hear drums and the sound directs you to an innocent-looking boy (not a real one) playing tin drums and sitting dangerously on the edge of a high wall. It is a reference to Günter Grass’s film The Tin Drum, where the protagonist plays his instrument whenever there is a crisis.

There is even a scene where the drumming disrupts a Nazi rally. The meaning of “to beat a tin drum” is to stir up disturbance in the spirit of resistance. The drumming of this boy, out of nowhere, is meant to create a disturbance during art appreciation in a quiet and peaceful museum.

There was also another mechanical boy, looking again like Cattelan, on a bike, which suddenly appeared.

As I left the exhibit, I saw a bum in tattered clothes. He was so off, and did not fit in the art-filled environment. I think he was part of the Cattelan exhibit as well. I saw photos of the “bum” in various locations beside the artworks. With Cattelan, this is possible. I wonder what his presence was supposed to mean, though.

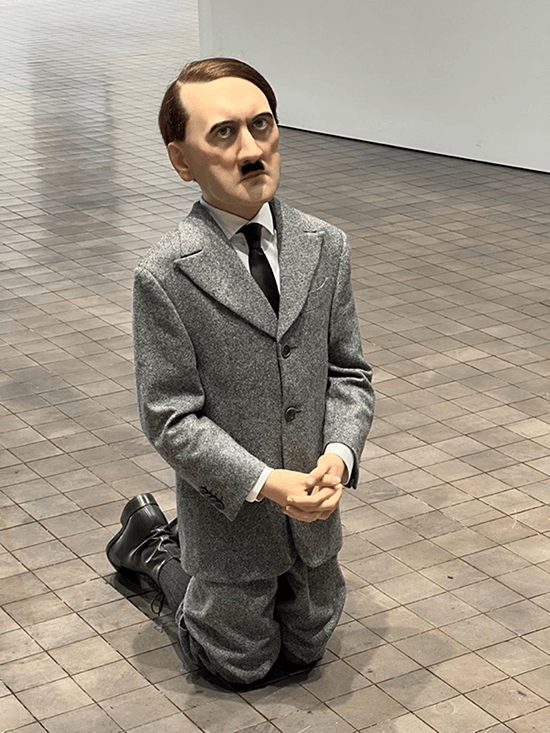

I was then led to what seemed like a statue of a young schoolboy kneeling, and as I got closer, I realized that it was Adolf Hitler (“Him,” 2001).

Cattelan is famous for thought-provoking work and asks uncomfortable questions. This artwork dwells on a definitely sensitive subject, namely, one of the most ruthless men in history. Yet, he is praying and seeks forgiveness. Cattelan asks the question: “If Hitler had repented, could he have been forgiven?” or “What do forgiveness and reconciliation entail?”

I then go to the Mona Lisa of the exhibit, the “piece de resistance among the other pieces de resistance”—that iconic banana under duct tape, “Comedian.” It was just there in its hundred-thousand-dollar glory, a simple fruit absurdly taped to the wall.

The museum explains the piece: "Cattelan jumps into the heart of the contradictions in the art world, and how it decides what art is and its worth. “Can a banana, destined to decay, become art? How does it make you feel to know that a series of actions so banal were sold at such a high price? Out of so many options, why a banana?”

Cattelan’s 1999 “La Nona Ora” created quite a scandal. A meteorite knocks down Pope John Paul II on a red carpet. Very strange, very absurd, and yes, I was a bit taken aback. It looked so real. Is this a criticism of authority? I wondered. Since this work was presented, there have been numerous debates on what it means and represents. Whatever it is, the work challenges the social conventions and perceptions of people.

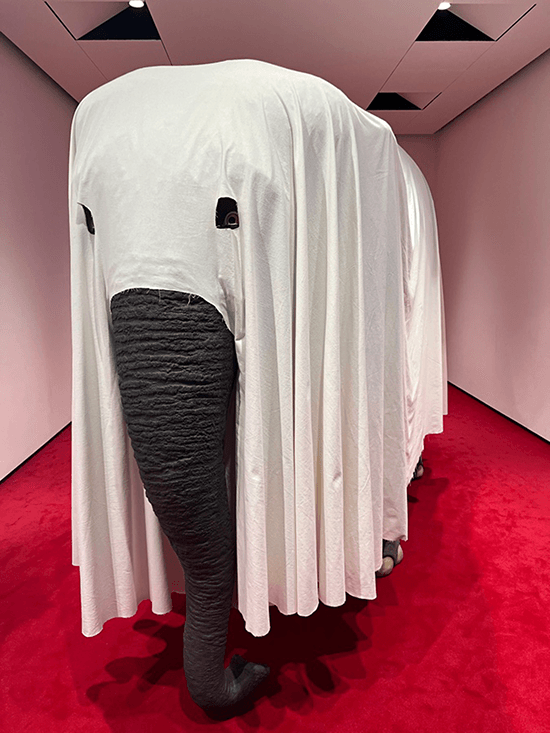

Then there was the “elephant in the room,” literally and figuratively. A humongous baby elephant covered in a white cloth with holes for eyes and nose sits quietly in the exhibit. It depicts an obvious issue that no one wants to talk about.

The white cloth is also similar to those worn by the Ku Klux Klan, expressing racial issues. This work was first shown in New York in 2000, “where its covered presence implied the artist’s inclination to flight while pointing to the racial conflicts deeply rooted in US society.”

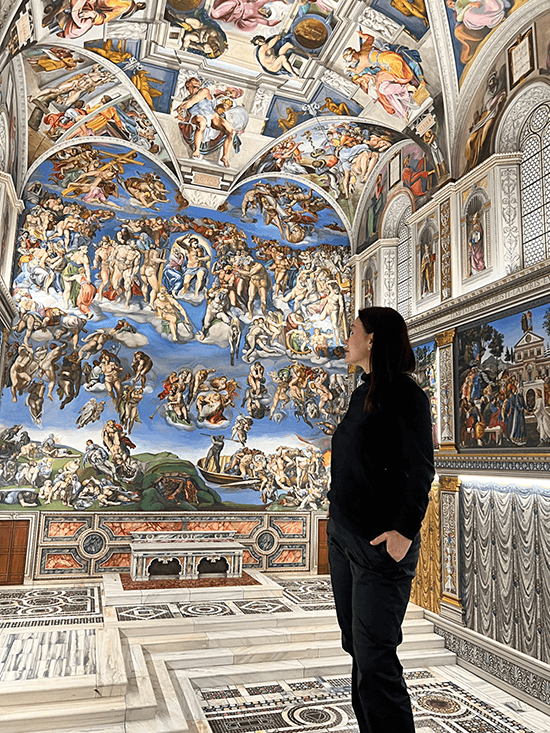

The journey ends with a fantastic replica of the Sistine Chapel. Cattelan reproduced the ceiling frescoes of Michelangelo to the minutest detail in a miniature-but-big-enough-to-walk-in replica. Here, you can see the art up close and even take photos and videos, unlike in the real Sistine Chapel, where it is banned.

This mini Sistine Chapel begs the question, “Do replicas strengthen or undermine the authority of the original?” Leeum Museum states, “Cattelan’s replication expands the question of originality in today’s world where we often encounter art through image and various reproductions.”

There was a lot of Maurizio Cattelan to cover in this impressive exhibit, and to absorb all the art and its meanings, one needs to go back. Maurizio Cattelan continues to stir up social issues, providing a dash of his dark humor, his brand of absurdity, and uneasy topics. But most of all, he makes you think about his art and what they are about—which, days after, I continue to do so.

* * *

To learn more about “WE,” a solo exhibit by Maurizio Cattelan at the Leeum Museum in Seoul, visit leeum.org.