China’s hidden century of resilience and creativity

China is always a hot topic because of its sheer size and population, not to mention its political and economic influence, felt in every corner of the world. With its proximity to the Philippines, a long history of trade and cultural exchanges, a significant Chinese community in the country and the unresolved issues in the South China Sea, it remains ever-present in our consciousness, so much so that we just had to see the British Museum exhibit, “China’s Hidden Century.”

To understand the modern nation that it has become today, we have to look back at a pivotal period in China’s history that acts as a crucial bridge of illumination—the “long” 19th century that stretches from the accession in 1796 of the fifth emperor of the Qing dynasty, Jiaqing, to the abdication in 1912 of the 11th, Puyi, who was a five-year-old boy.

Qing (meaning “bright”) was the name assumed by the Manchu warriors who defeated the existing Ming Dynasty in 1644. The 1800 All Under Heaven Complete Map of the Everlasting Unified Qing Empire, composed of eight scrolls, magnificently opens the exhibition with its vast expanse of blue seas that mirrored the pride of a growing empire. It’s an aerial view—one can imagine the emperor hovering, godlike, over the South China Sea, a feeling that the present China may be trying to relive with its present geopolitical claims and desires.

By 1796, the Qing ruled over one-third of all humanity and was one of the most prosperous empires in world history. With cataclysmic events, however, the country collapsed in 1912, bringing an end to some 2,000 years of dynastic rule and giving way to a revolutionary republic. It’s known as the “hidden century” because this era was thought of as so dark, violent and shameful due to famines, foreign invasions, wars and dynastic disintegration.

The Taiping Civil War (1850-1864) alone, between the Manchu-led Qing dynasty and the Hakka-led Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, cost more than 20 million lives in a population of 400 million.

A shocking lithograph shows a British opium factory in India preparing 300,000 blocks of opium to flood the Chinese market in 1851, putting the drug lords of Narcos to shame. This came after the First Opium War, when the Chinese emperor complained that addiction was ruining his empire and the British unleashed their guns. China lost and had to hand over Hong Kong with the Treaty of Nanjing.

With the Second Opium War, the old Summer Palace in Beijing was destroyed and looted by French and British soldiers in 1860. A shattered fragment of the palace is on display, beside a portrait of a dog appropriately named Looty, brought all the way back from the devastation to be presented to Queen Victoria as one of the first Pekingese to enter Britain.

Despite this tragic backdrop, the events and people of 19th-century China launched the country on a far-reaching, multifaceted quest for modernity. Survivors of this century’s dislocations, from various social classes and economic groups, demonstrated amazing resourcefulness and creativity, both driving and embracing cultural and technological change in painting and politics, war and craft, literature and fashion.

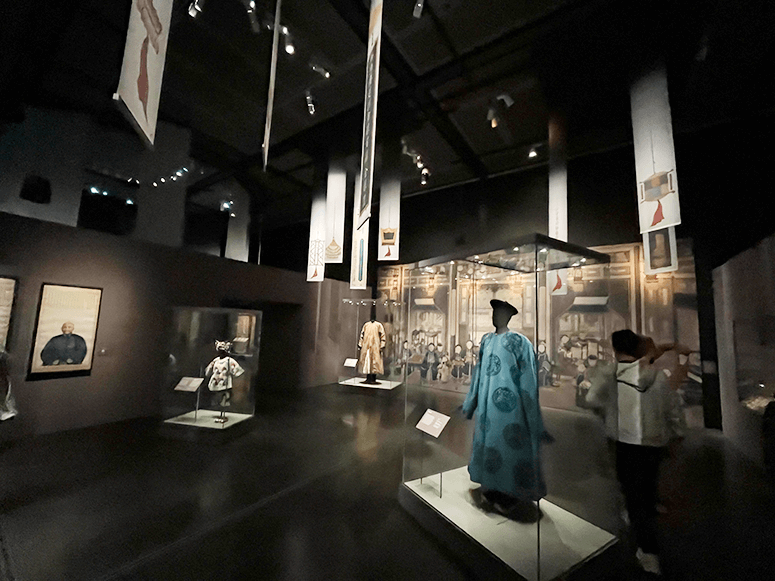

The result of a four-year research project led by the museum and London University, involving over 100 scholars from 14 countries, the exhibit consists of 300 objects, with a focus on individual groups of people so that viewers get to experience the visual richness of the era through the material culture of multiple sections of society. This point of view humanizes the century that has been dismissed globally as a period of China’s decline.

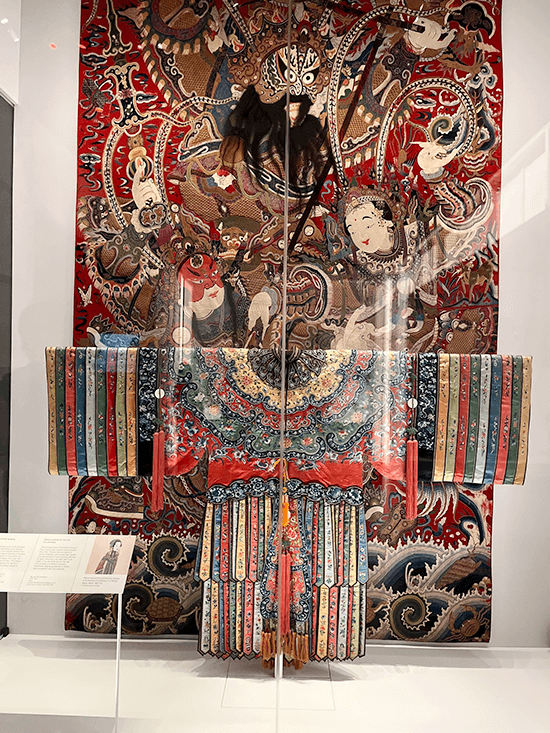

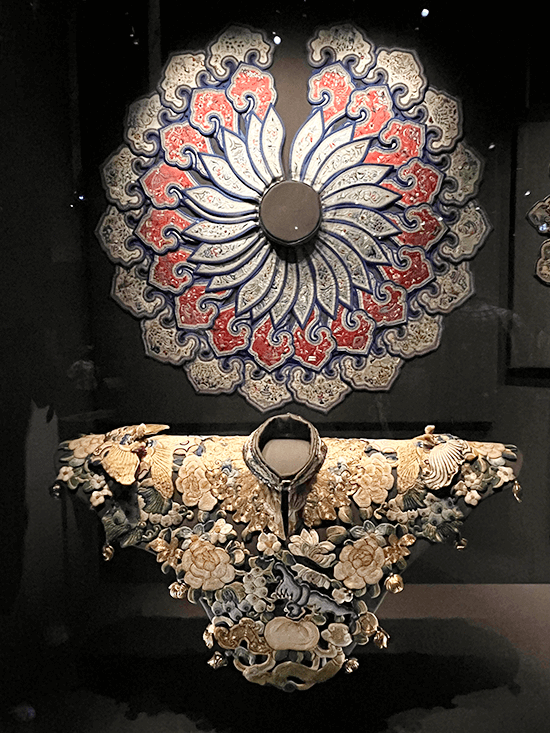

In the court section, a stunning robe of the Empress Dowager Cixi features a swooping phoenix amid lush chrysanthemums and wide sleeve bands—combining Manchu, Chinese and Japanese motifs. Considered opportunistic, ruthless and malicious, with a passion for power and intrigue, Cixi rose from low-ranking imperial concubine to regent, dominating the reign of three child emperors from 1861 to 1908. Extremely vain and delighting in extravagant ritual, she changed outfits 10 times a day and her wardrobe contained hundreds of dazzling pieces that she accessorized with grandiose, jeweled headpieces.

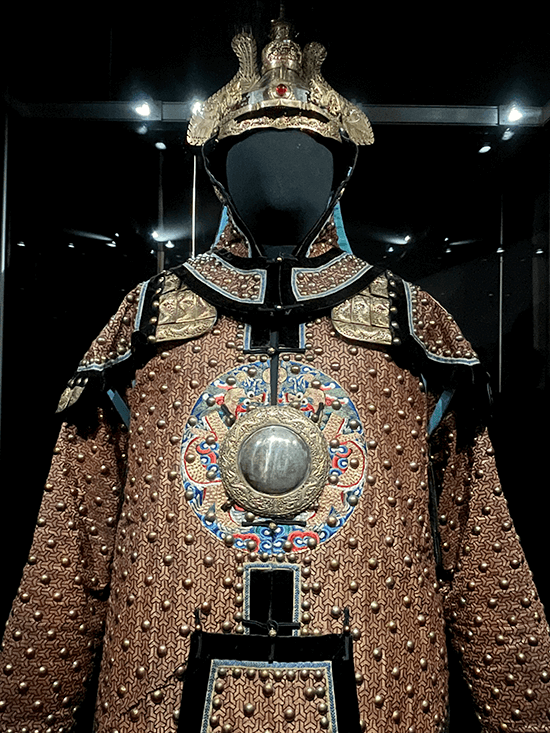

The military gallery devoted to the elite soldiers called Bannermen has a dramatically lit uniform in silk, steel, wood, leather and lacquer with studs and ornamentation in gold and silver. Weaponry is no less elaborate, embellished in tortoiseshell and fish skin.

The Artists section explores the traditions that were upheld, placing value on technical skill while introducing more modern influences. The artist Ren Xion and his beautiful portraits represent the new breed, particularly in Shanghai: a cosmopolitan hub where artists displaced by the war reinvented themselves by responding to fresh encounters with visual and material culture and technology.

Urban life in cities was difficult, but some enjoyed incredible wealth, as seen in lavishly embroidered collars and headdresses. Representing those on the other end of the spectrum is a challenge because not much survives but a waterproof dried-leaf raincoat for farmers and fishermen, similar to the one we have in Batanes, which was found and restored to its original state after months of conservation work.

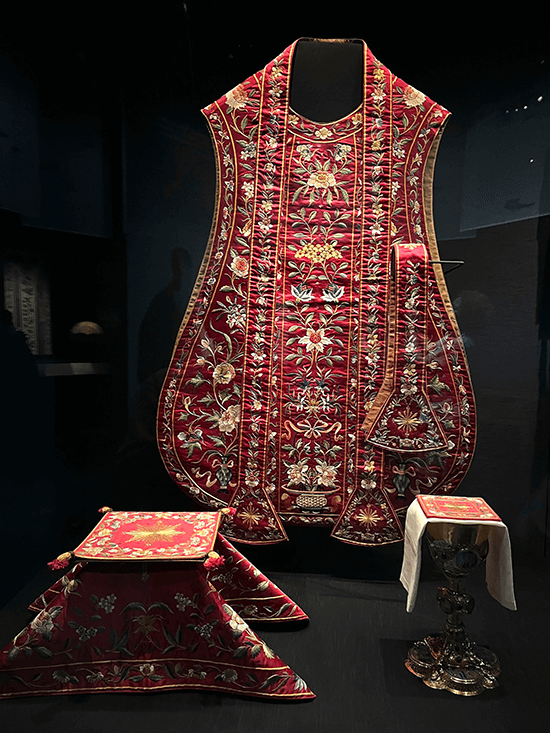

The quality of goods that were being exported from China in the 19th century was nothing short of exceptional, a fact that we know only too well as the transshipment point in the Manila Galleon Trade. A section of luxury items from silver to hand-carved ivory pieces illustrate the bustling trade that transformed Guangzhou (Canton) into the international port and major industrial city that it is today.

The final gallery is devoted to “Reformers and Revolutionaries,” epitomized by the poet and feminist Qiu Jin. Writing about the injustices of being forced to be a lady and joining anti-Manchu revolutionary groups, she supported the republican cause in 1905 and was executed by beheading for it. Her brutal death became a pivotal event to galvanize support for the revolution, which overthrew the Qing Empire in 1911 when Qiu Jin was celebrated as one of the famous martyrs. She remains a role model from China’s most tumultuous period, one its people faced with bravery, resilience and creativity.