Lanvin: Fashion born out of a mother’s love

Like Coco Chanel and Elsa Schiaparelli, Jeanne Lanvin was celebrated and enjoyed great success after the 1918 Spanish Flu, though she may be the least known of the three designers.

No surprise there since she shunned the spotlight and avoided large gatherings in the couture circle. Unlike Chanel, who hobnobbed with aristocrats and business tycoons, she preferred a creative group of artists, musicians, designers and writers.

Once in a while she would be seen at the horse races but only to do R&D: to see what women were wearing, what was flattering and what wasn’t, which fabrics and silhouettes worked. With her observations she not only improved on the clothes she was currently making but also predicted what women would be desiring next.

She rarely socialized with clients and downplayed her image, unlike her two rivals who were tireless self-promoters.

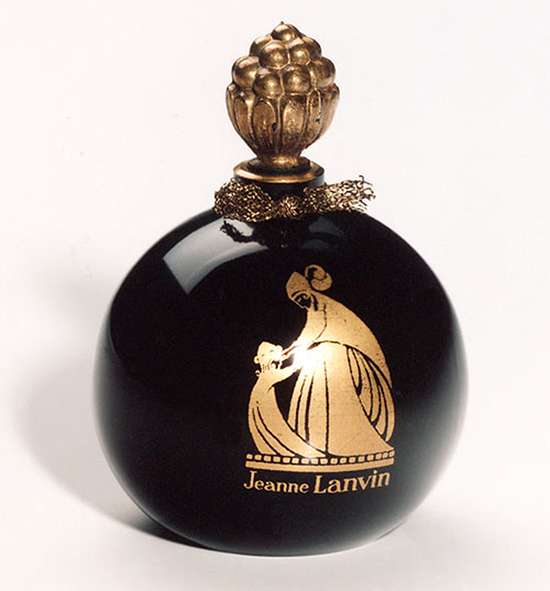

Self-effacing as she was, she became one of the greatest designers of the 20th century. In the 1920s, the house of Lanvin was a full-blown lifestyle brand that had expanded into perfumes and household goods.

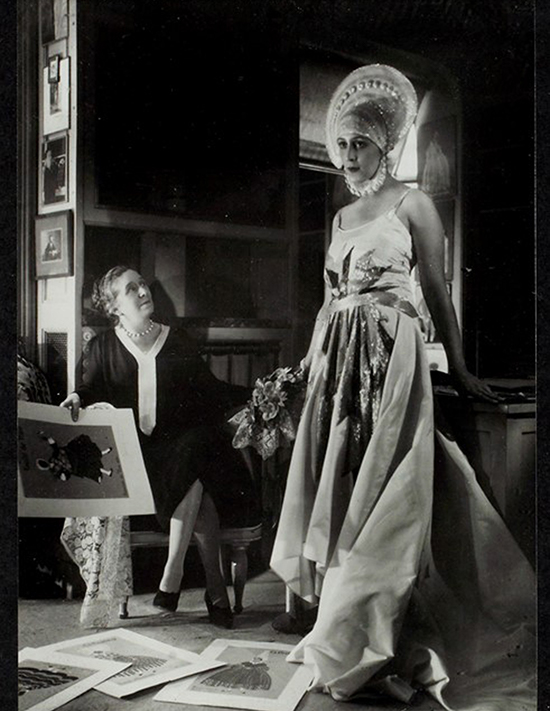

“Her image was not as strong because she was a nice old lady and not a fashion plate,” Karl Lagerfeld wrote of her. Unlike the embellished dresses in vibrant colors that she created, Lanvin wore discreet black and white outfits with pearls, which were more like the utilitarian Chanel signature.

Self-effacing as she was, she became one of the greatest designers of the 20th century. In the 1920s, the house of Lanvin was a full-blown lifestyle brand that had expanded into perfumes and household goods and was the first Parisian house to have a made-to-measure menswear line.

“Men, women, children, perfume, decoration: all of the departments that constitute a fashion house, she had at the beginning of the 20th century,” says fashion curator Olivier Saillard.

Quite a feat considering that women at that time were confined to domestic roles and the running of businesses — including haute couture — was largely the domain of men.

Ironically, it was domesticity that launched her brand to become a powerhouse. Born in Paris in 1867 as the eldest of 11 children, she spent most of her youth as a seamstress and milliner’s apprentice until 1885, when she was able to establish her own millinery workshop and opened a house in 1889.

Lanvin married the Italian aristocrat Emilio di Pietro in 1895 and, though the marriage was brief, ending in 1903, they had a single child, Marguerite, who would change the course of her life as well as the world of fashion.

As soon as her daughter was born, Lanvin embraced motherhood and made Marguerite the center of her world, dressing her up in the most beautiful dresses using the most luxurious fabrics that attracted the attention of society women.

A photograph of the mother and daughter at a costume party wearing matching outfits made them even more popular and this became the basis for the company logo, which was a coup in branding. This prompted the opening in 1908 of the children’s clothing department, which became so lucrative that a ladies’ department was opened the following year when women wanted adult versions of the garments.

Marguerite continued to be Lanvin’s inspiration as she grew older, resulting in pieces that were always feminine while providing a youthful slant to the designer’s creative ideas, which found fruition in one of her greatest contributions to fashion: the robe de style.

This dress took cues from the 18th century, using panniers, an elongated torso and a romantic full skirt that created a large canvas for ornamentation. It flattered every figure at every age for all occasions, a viable alternative to the slender, cylindrical silhouettes of other couturiers. Lanvin did her version of a narrow Empire waistline dress that had long, trailing sleeves, which was also popular because it complemented most body shapes.

What also contributed to her success was the fact that she opened a dye factory that created exclusive colors that others could not duplicate, such as Rose Polignac invented for her daughter, Fra Angelico blue and Velasquez green. Her references were rich, thanks to her being well travelled, resulting in designs and adornments that referenced the various cultures she encountered.

This tradition continues today with Bruno Salielli, who joined Lanvin in 2019 as the house’s youngest creative director of the oldest fashion house in France, providing a pioneering spirit as he plays with unlikely combinations like medieval motifs and manga. His urban planner father and Tunisian-born costume designer mother helped shape his multicultural, multidisciplinary perspective.

For spring 2022, he embarked on a “bold, joyful, free and unapologetic proposition,” exploring 1940s Batman comics, Pop-Art prints and Art Deco with styles and cultures freely mixing together as they do in his beloved animé: “Like a dream village in Pinocchio made up of a Bavarian church and an English house, and all this is mixed and looks new.”

His intuitive approach while employing the finest craftsmanship brings to mind what Lanvin told Vogue in 1934: “I act on impulse and believe in instinct. I am carried away by feeling, and technical knowledge makes it a reality.”

The youthfulness of his pieces, with nods to childhood memories in his native Marseille and the influence of his parents, also brings the filial roots of the house to full circle. He could almost be the Jeanne Lanvin in the logo dancing with his muse, giving rise to one of his many creations that are gaining many fans today, just as the founder’s dresses made many women happy and confident then.