Fashion and art merge in Schiaparelli Exhibit

The eternal question of whether fashion can be considered art can probably be answered convincingly with the ongoing exhibit “Shocking! The Surreal World of Elsa Schiaparelli” at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

Considered obscure compared to her contemporaries like Coco Chanel and Madame Vionnet, Schiaparelli never really made a clear-cut distinction between the two, creating garments inspired by past and present art and collaborating with the most significant artists like Salvador Dalí, Jean Cocteau, Meret Oppenheim, Elsa Triolet and Man Ray.

The designer actually came from an intellectual and artistic background. Born to a Neapolitan aristocrat mother and an accomplished Orientalist scholar father, she grew up in a Roman palazzo and studied philosophy.

She considered herself an “ugly” child but sought to transcend the condition by planting seeds in her throat, ears and mouth so that she could have “a face covered with flowers like a heavenly garden.” The incident would be recalled in a dress she later designed with appliqués of seed packets and at recent shows of Thom Browne with transformative shrub makeup and Loewe’s coats, jeans and sneakers that sprout grass — demonstrating her influence almost a century after the prime of her career.

She was always a rebel, writing a book of poetry that scandalized her family, who sent her promptly to a Swiss convent school. Defying her parents’ wishes for a suitable life and husband, she went on her own, escaping to London, New York and later to Paris, where she established her own fashion house.

“She was patiently erudite and brilliant, and from this brilliance, she created a life and a celebrated body of work — with an elaborate grammar and an emancipated vocabulary — an achievement not within everyone’s reach,” says curator Olivier Gabet. “It’s very interesting for us to show that she has this visual and literary culture that very few people had at the time.”

Although she had the foundation of art history, she thought “it was futile to attempt to dig fashion inspiration out of a dead epoch. We live in an age of steel and skyscrapers, not sighs and sofas.” No wonder she appealed to the modern woman, having a first international hit in 1927 with her hand-knit trompe l’oeil bow sweater that capitalized on how women wanted something different and artful while being addicted to the sweater look.

The sweater in the exhibit is one of 212 silhouettes and accessories by Schiaparelli herself, among 577 works that include paintings, sculptures, jewelry, perfumes, ceramics, posters, and photographs by her artist friends and contemporaries. Adding excitement to the show are creations designed in her honor by fashion greats Yves Saint Laurent, Azzedine Alaïa, John Galliano and Christian Lacroix.

The introductory room has walls lined with hundreds of drawings of the couturière, overwhelming the viewer with the extent of her oeuvre. From here, one witnesses her awakening to fashion and modernity alongside the defining role of Paul Poiret as mentor in 1922. Although she designed practical and comfortable sportswear like cardigans and beach pajamas, Elsa reacted against the simplicity and muted color palette of Chanel and other designers by using bold, contrasting colors, including her signature “shocking pink.”

After her bow sweater created a sensation, she developed a taste for Art Deco, collaborating with Jean Dunand, who designed for her a dress with lacquered, painted pleats.

Inspired by the Surrealist aesthetic, she introduced witty decorations, patterns and accessories, designing gowns decorated with lobsters, flower vases, news articles reviewing her collections (predating Galliano), canceled stamp patterns, buttons in the form of tiny snails and collars made of feathers and monkey fur. She developed a fruitful relationship with Man Ray, who was inspired by her, as seen in his photographs that feature her as a model.

Aside from the use of embellishment, she made her pieces distinctive through cuts and silhouettes, exaggerating particular features like the shoulders through padding.

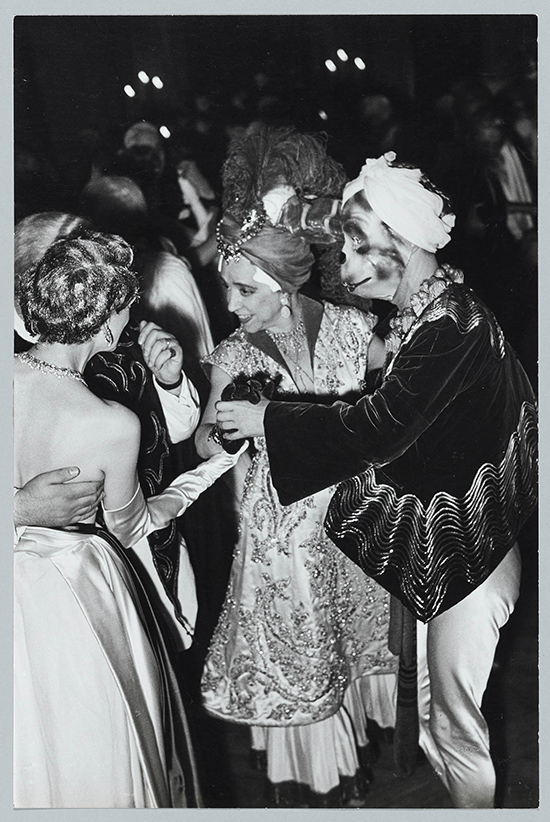

Next, her thematic collections, which she had been presenting starting in 1935, take center stage. Presented at her salon with theatrical staging and dramatic lighting, the show’s front rows are filled with royalty, politicians, artists and film stars who “pushed towards the models like it was rush hour,” recalls a fashion editor. An exquisitely embroidered jacket from her Zodiac collection (FW1938-39), one of her most imaginative collections, had proportions that were built upon the strictest measurements based on Euclid’s treatise on geometry.

Aside from the use of embellishment, she made her pieces distinctive through cuts and silhouettes, exaggerating particular features like the shoulders through padding. She was also adventurous in experimenting with fabrics and fastenings, mixing metallic and wool yarn and even glass and plastic for textiles and using zippers and metal clips instead of buttons.

Another collection from 1939, a full-length jacket, was based on the 16th-century Commedia dell’arte, referencing characters like the Harlequin, who was known as a prankster with a costume covered in random patches of every color that later evolved into blue, red and yellow diamonds.

She always did the unexpected, using the idea of displacement, where a chosen object is removed from its usual environment, modifying its original purpose, just like her collabs with Salvador Dali: a 1936 suit with bureau-drawer pockets and the famous Shoe Hat.

Bringing us back to the present are the pieces designed by the current creative director, Daniel Roseberry, whose couture creations for Schiaparelli are imbued with as much imagination and whimsy that have made them favorites on the red carpet and even chosen for President Biden’s inauguration when Lady Gaga sang the national anthem in his voluminous ball gown in patriotic colors, punctuated by a stunning dove of peace brooch. As Monsieur Gabet said in an essay, “He is truly a worthy successor who personifies the contemporary relevance of what Schiaparelli has represented for nearly a century. She loved to dress women, not to disguise them, but to elevate them.”