Obama on racism, democracy and Trump

A few weeks before A Promised Land, Barack Obama’s latest memoir, came out, Dave Chappelle was hosting Saturday Night Live. It was very soon after a contentious Election Day, and half the country believed Joe Biden won; the other half were angrily denying Trump had lost. Chappelle was there in the middle, shrugging about his plight as a Black stand-up comic — that, as a Black man in America, he always had to wear a mask, “disguise” every truth he told in a punchline.

This is a condition Obama had long internalized by the time he ran for president in 2008. There were certain political truths, such as that succeeding as a Black candidate in America meant not being too Black.

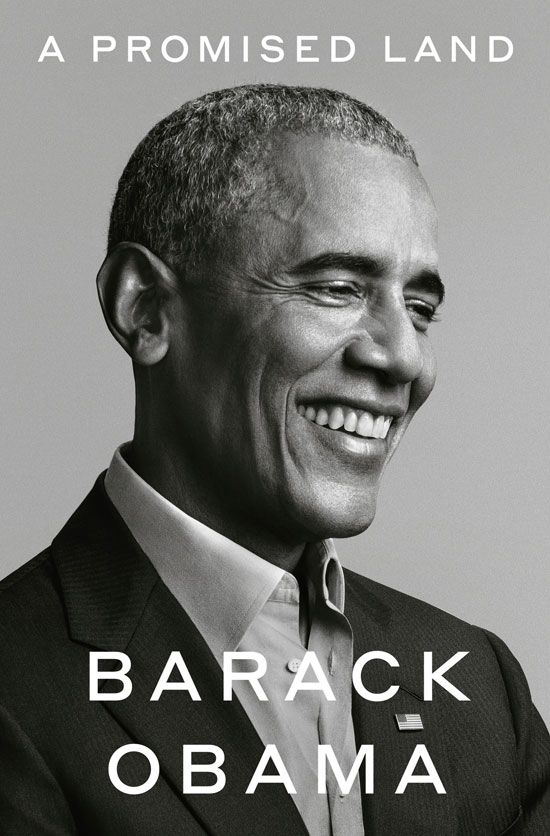

Barack Obama’s memoir comes at 768 pages and sold for 1.7 million copies in its first week

“Too much focus on civil rights, police misconduct, or other issues considered specific to Black people risked triggering suspicion, if not a backlash, from the broader electorate,” he writes. “You might decide to speak up anyway, as a matter of conscience, but you understood there’d be a price.”

Though he admits he didn’t take Trump seriously at the time, the former president sees in retrospect what was up

Obama learned the price — fast. Not only did he inherit a housing market collapse that left the economy teetering on the brink of Depression, he had to tell many white people to clean up their act — in the banking industry, in the auto industry, and in Congress, all of them having their own agendas — but he had to do it in a gentle, non-threatening voice. He couldn’t afford to piss off a country that gave the presidency to the first-ever African-American on a gamble, really. It would take finessing.

The first part of A Promised Land tracks young Obama — a familiar story of a smart guy who married the right woman and had an idea of unifying people through what he called “the audacity of hope.” But as much as young Obama sees his vision as a way of “bridging” political, ethnic and economic divisions, it does sometimes feel — even in his own telling — more like political ambition: a kind of inner GPS, an instinct that disregards odds, the way a heavy gambler or addict might pooh-pooh the risks. But of course, it’s really a combination of the two — idealism and unshakable confidence — necessary for any politician to survive. “Maybe it was impossible to disentangle one’s motives,” he concedes.

Still, here we can hark back to a time when a US president actually looked upon the duties of the Oval Office with a sense of awe — was it really so long ago? — instead of the chore that his successor found it to be. Here, Obama waxes poetic: “I would never fully rid myself of the sense of reverence I felt whenever I walked into the Oval Office, the feeling that I had entered not an office but a sanctum of democracy. Day after day, its light comforted and fortified me, reminding me of the privilege of my burdens and my duties.”

For millions of Americans spooked by a Black man in the White House, (Trump) promised an elixir for their racial anxiety

Contrast Obama’s awe with Trump’s reported quip that, next to his golf club properties, the White House was “a real dump.”

Obama also goes to lengths to depict his own transition — taking over from outgoing George W. Bush — as an exercise in mutual respect and dignity. “W” warned Obama he was in for “a hell of a ride,” but reminded him to “appreciate it every day.” Compare that to the ongoing transitionus interruptus Trump unleashes as he reluctantly prepares his exit.

There is, unavoidably in A Promised Land, the specter of that very elephant who came to occupy the Oval Office after Obama — the one whose “birtherism” claims and attempts to dismantle Obamacare became an obsession.

Though he admits he didn’t take Trump seriously at the time, the former president sees in retrospect what was up: “For millions of Americans spooked by a Black man in the White House, (Trump) promised an elixir for their racial anxiety,” Obama writes. “It was as if my very presence in the White House had triggered a deep-seated panic, a sense that the natural order had been disrupted.”

The first volume (yes, there will be a sequel) ends in 2011, with the White House Correspondents’ Dinner in which Obama famously roasted Donald Trump’s hints about a presidential run — thus setting the stage for the ominous winds that would, five years later, come to sweep through the White House.

We see Obama as a man obsessed with his own idea of America, of its perfectibility — or at least something closer to perfectibility

But the bitter winds were already in play when Obama took office in 2008. Rather than a “honeymoon,” he had to rush to get economic bailout packages through a non-budging pack of Republican Senators, notably Mitch McConnell, who reportedly shrugged off entreaties from Obama himself with a withering putdown: “You must be under the mistaken impression that I care.”

Obama regards McConnell as a “shameless” political operator who only cares about winning. The problem is, most people expect Democrats to rise to some higher moral level than people like McConnell — as dramatized when bank CEOs met with Obama to complain about their huge bonuses being cut during the bank bailout crisis. They called on Obama not to “fan the flames of populist anger with rhetoric” by pointing out that accepting $150 million in bonuses while the country was reeling from a housing collapse was unseemly. “I was stunned,” writes Obama. “You think it’s my rhetoric that’s made the public angry?” he told the CEOs.

Being a scold — whether it’s reminding CEOs not to be too greedy, or urging people to wear masks during a pandemic — is often a thankless duty that falls on Democrats.

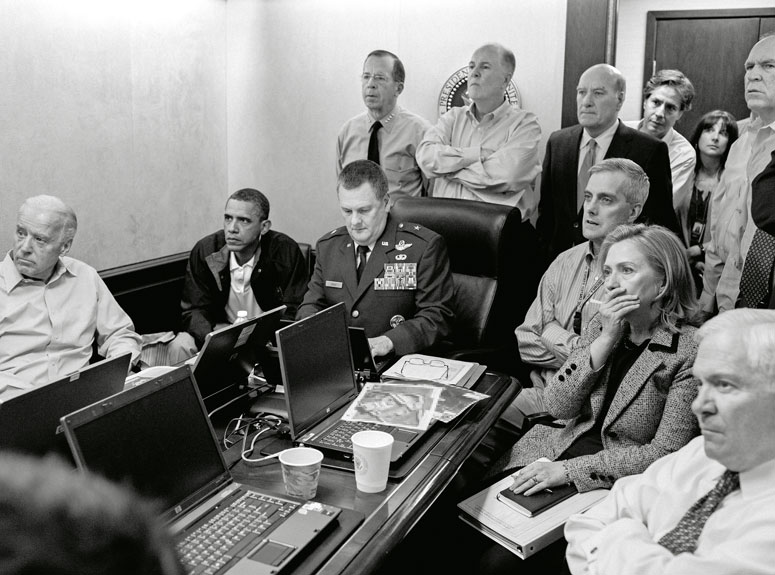

When he wasn’t navigating the right wing radio hosts and Republican politics, Obama showed steely resolve in passing the Affordable Care Act and taking out Osama bin Laden. Through it all, as contrast, A Promised Land offers some warm details of the work-life balance Obama was trying to strike with wife Michelle and his two daughters (Michelle Obama’s earlier memoir, Becoming, sold 16 million copies, though Barack’s latest may be on pace to beat that); his own weaknesses (a cigarette habit that grew and grew in his first year in office); and an admitted difficulty at times to “get to the point” in his rhetoric (he often had a prickly relationship with the press).

The idea of America, the promise of America: this I clung to with a stubbornness that surprised even me

We see Obama as a man obsessed with his own idea of America, of its perfectibility — or at least something closer to perfectibility. Today’s AOC followers would probably label Obama as way too moderate. But at heart, he’s a centrist who’s seen enough minority suffering to ignore it, but who’s also too practical to think you can succeed by tearing the whole system down. “I chafed against books that dismissed the notion of American exceptionalism; got into long, drawn-out arguments with friends who insisted the American hegemon was the root of oppression worldwide. I had lived overseas; I knew too much,” he writes. “That America fell perpetually short of its ideals, I readily conceded. The version of American history taught in schools, with slavery glossed over and the slaughter of Native Americans all but omitted—that, I did not defend. The blundering exercise of military power, the rapaciousness of multinationals—yeah, yeah, I got all that. But the idea of America, the promise of America: this I clung to with a stubbornness that surprised even me.”

The image one gets of Obama is of a man trying to surf the wave of some very conflicting, turbulent waters in America. (He is from Hawaii, after all.) He was not only trying to find a bridge between increasingly gaping divisions — between nationalism and legitimate criticism of US policy, between racism and white resentment — that would arise during and after his presidency; he was trying to do it all with… a speech. Through logic and rhetoric. And the unfortunate reality is that a speech, even if you believe in it wholeheartedly, will only navigate you through, if you’re lucky, the political moment. It will not change the reality on the ground.

The last four years in America have shown ample proof of that.