Vintage maritime accounts debunk China's claim

Libreria Filipiniana often appears on FB to offer titles that are scarce. Sometimes they’re recent books, of late having included Rethinking Filipino Millennials: Alternative Perspectives on a Misunderstood Generation, edited by Jayeel Cornelio, 2022 National Book Awards winner for Social Sciences, and a “Heritage Architecture Bundle” that includes Diksyonaryong Biswal ng Arkitekturang Filipino by Rino D.A. Fernandez, published in 2015 as a hardbound edition.

An item aroused curiosity some weeks back, despite only sharing References to vintage accounts on maritime traditions in Asia-Pacific, plus some quotes, with “©️ Credits to Owners.”

These include: “Heng, Derek (2019). Ships, Shipwrecks, and Archaeological Recoveries as Sources of Southeast Asian History. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History …; Pham, Charlotte Minh-Hà (2012). Asian Shipbuilding Technology. Bangkok ... ISBN 978-92-9223-413-3; Dick-Read, Robert (2005). The Phantom Voyagers: Evidence of Indonesian Settlement in Africa in Ancient Times …; Manguin, Pierre-Yves (September 1980), ‘The Southeast Asian Ship: An Historical Approach’. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies; Manguin, Pierre-Yves. 2012. “Asian ship-building traditions in the Indian Ocean at the dawn of European expansion” …; and Worcester, G. R. G. (1947). The Junks and Sampans of the Yangtze, A Study in Chinese Nautical Research ….”

In a pseudonymously written argument, some paragraphs that drew my attention provide interesting excerpts:

“Is China’s claim of Nine-Dash line based on history relevant in modern times today? In fact, Southeast Asia maritime people controlled first the Nine-Dash before China accepted the transfer of navigation technology…

“Did you know that Chinese maritime shipping did not exist until the end of the Song dynasty (from the 12th century); before that their ships were river ships. However, large Austronesian merchant ships that docked in Chinese ports with four sails were recorded by scholars as early as the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD). They are called kunlun bo or kunlun po (lit. ‘ship of the dark-skinned Kunlun people’). They were ridden by Chinese Buddhist pilgrims for trips to South India and Sri Lanka.

“The 3rd century book Strange Things from the South by Wan Chen describes one of these archipelago ships as capable of carrying 600–700 people …

“The South Chinese junks were based on the multi-bladed and keeled Southern/Austronesian country ships (known to the Chinese as po, actually from the Javanese word ‘prau’ or Malay ‘perahu’ —formerly a big ship). …

“The Song dynasty developed the first junks based on Southeast Asian ships. During this era they had also adopted the sails of Austronesian junks. Song dynasty ships, both commercial and military, became the backbone of the next Yuan dynasty’s navy. In particular, the Mongol invasion of Japan (1274–84), as well as the Mongol invasion of Java (both failed), largely depended on their newly acquired Song naval capabilities.”

The writer then argues:

“Supposedly, the Indonesians who have the right to inherit the Kunlun nation should have the right to claim the NINE-DASH LINE, because they were the first to control this sea area; the peak of its glory was in the era of the Sriwijaya Empire. The Chinese were very late in developing their first Ocean ship, which was only in the 12th century AD, while the Indonesians had sailed in the ocean before AD.

“Claiming ocean areas based on ancient history is absurd and irrelevant to geopolitical developments.”

One can’t help but agree with these contentions, which practically render as preposterous China’s claim of its primacy as part of ancient lore, that only its seafarers that lorded it over the South China Sea. Why, we can also cast additional scorn on this fairy tale of a nine-or-ten-dash-line.

Has there been any other country that has set a precedent for China’s claim over an entire sea, simply by citing supposed early history? Just because it’s named South China Sea doesn’t mean it’s theirs. India has never laid claim to the Indian Ocean, nor Japan the Sea of Japan, Ireland the Irish Sea, etc. A body of water is named for a proximate country for geography’s sake, thanks to early map-makers.

But the bully-boy has not only rescinded its earlier compliance with UNCLOS (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea), as one of the first countries to sign it, on December 1982, and even ratified the convention in 1996.

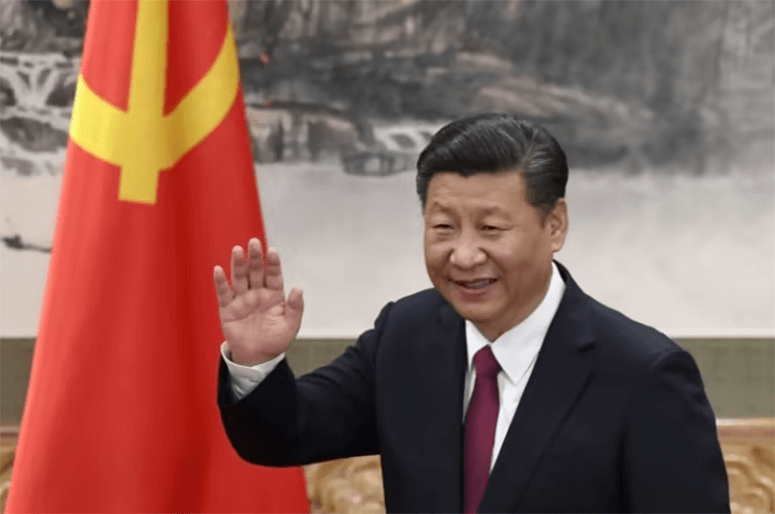

When its present leadership weighed PROC’s growing economy and influence against the Philippines’ call for adjudication during President Noynoy Aquino’s term, greed appeared to get the better of Xi Jinping’s rush toward global dominance.

Earlier, PROC had seemed to patiently anticipate the fulfillment of historians’ and economic observers’ futuristic take that the century introduced by the new millennium would be China’s for the taking. It finally bared its agenda when the Philippines’ challenge, even before it merited the Hague Tribunal’s approval in 2016, clearly unveiled Chinese arrogance. The ruling threw cold water on the spurious claim of “historic waters” — or that China has historically controlled this maritime environment.

Had it continued to be led by sagacious statesmen who thrived in Confucian tradition, befriending all countries with humility and charm might have been the proper direction.

But no, Xi Jinping’s ego would not conform with his predecessor Deng Xiaoping’s oft-stated principles. A famous quote by the “General Architect” of reform within the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from the late 1970s to the late 1990s reads thus:

“China will never seek to be a superpower, to bully others, and will forever side with the third world countries.”

It was Xiaoping who spearheaded changes resulting in a booming economy, living standards, and expanded personal and cultural freedoms. At 82, he even agreed to avoid smoking in the presence of then-President Cory Aquino.

The problem with most countries is seldom the collective will of its people, but the ego of an autocrat who manipulates his power.

These years, these despots include Putin, Jinping, Kim Jong Un, and Netanyahu (also potentially Trump)—whose levels of misguided pride still seek to make up for historical embarrassments, recent or in the remote past. But they are not immortal. Being replaced by a successor cannot guarantee continuity of foolishness (even in North Korea). When can these leaders realize this? Or will it take another kind of ship, bearing sailors from another realm of space (or future) to get rid of them in one fell swoop?

In China’s case, it is not its people that Filipinos contend with for a sea’s blessings. However likely that Xi Jinping’s transparent agenda will be carried on or even made worse by the next generation of PROC leaders, there’s always a chance that someone rises after falling out of line, and correctly observes their country’s rightful place in the equality of nations.

Fairy tales can stay as fairy tales. And whatever previously imagined historic lore and fabled dash-line can be recalled with much laughter.