A lesser-known Lapulapu statue in Cebu has been blamed for the deaths of local officials

About eight kilometers away from the pomp and circumstance that marked the celebration for the 500th year of the Battle of Mactan at the Lapulapu monument in Mactan Shrine is a much older and less glamorous statue of the national hero that has a history checkered with alleged murders.

The Lapulapu statue in Lapu-Lapu City is the oldest in the country. But it is quite obscure that it does not even have its own Wikipedia entry.

But what it lacks in contemporary publicity, it gains in lore and oral history.

The statue was erected on Dec. 31, 1933 at the center of a town that was then called Opon. It was the first statue put up to honor Lapulapu in the country.

When it was built, the statue depicted a regularly-built Lapulapu carrying a bow and arrow aiming at the old municipal hall across the town plaza. It’s unrecognizable by a generation used to seeing him with bulging muscles and highly toned abs.

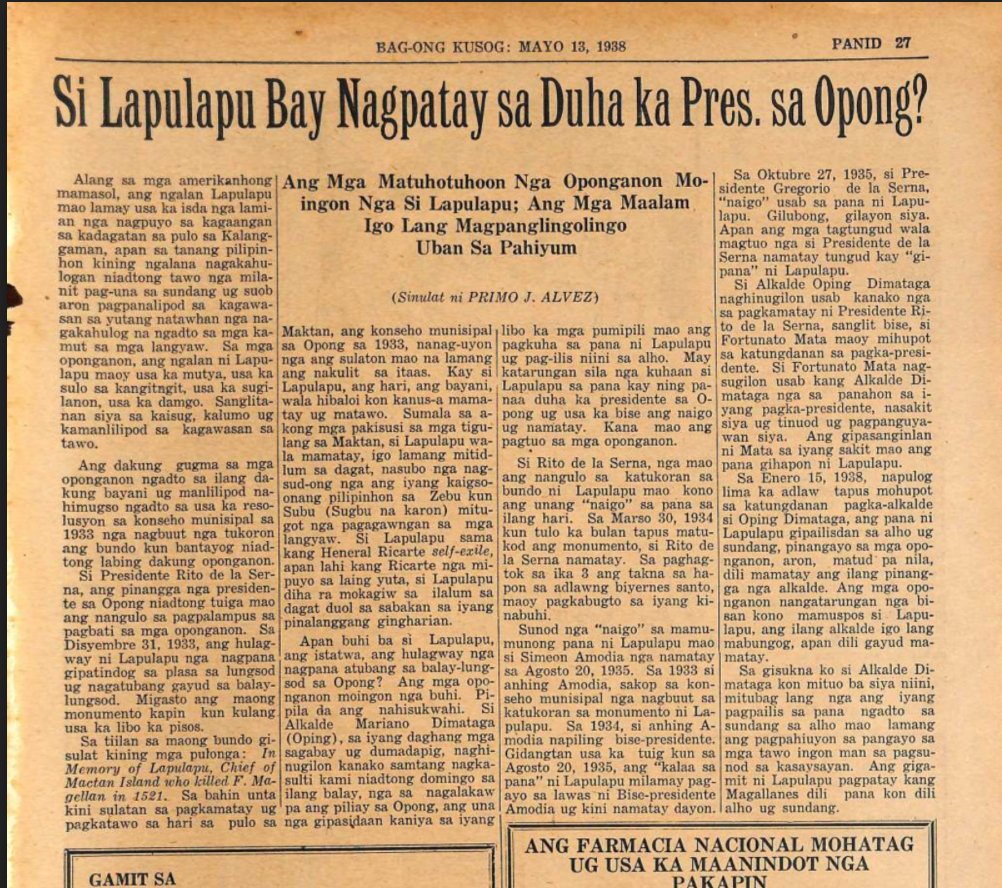

Three months after it was put up, the town mayor died in office. The report by the no-defunct news weekly "Bag-ong Kusog" said Opon Municipal President Rito de la Serna died on March 30, 1934.

The news article, published on May 13, 1938, went on to report the death of de la Serna’s successors: Simeon Amodia on August 20, 1935 and Gregorio de la Serna on October 27, 1935.

The title of the story was, “Si Lapulapu Bay Nagpatay sa Duha ka Pres. sa Opong?” which translates to “Did Lapulapu kill the two Presidents of Opong?”

Locals blamed the statue for their deaths, saying Lapulapu shot them with his bow and arrow. The Bag-ong Kusog story reported their deaths as naigo, using the Bisaya word for “hit.”

Even vice mayor Fortunato Mata, who briefly took over when President Rito de la Serna died, said he fell ill and blamed Lapulapu for it.

On January 15, 1938, 15 days after he took office, Mayor Mariano “Oping” Dimataga ordered that the bow and arrow be taken out and replaced with an alho or pestle on one hand and a kampilan or sword on the other. The alho figures prominently in the native folk tradition of Lapulapu according to a story saying Lapulapu killed Ferdinand Magellan using an alho. (In the 1930s, Cebu newspapers announced that Lapulapu’s alho and kuwako or pipe have been discovered and would be put on display in the Cebu Carnival. The daughter of the person who made that claim, however, later admitted to historian Dr. Reil Mojares that these were just old artifacts dug up and ascribed to the hero.)

Dimataga went on to become Opon’s longest serving mayor and the first Lapu-Lapu City mayor, when the town was renamed after the Mactan chieftain in 1961.

The story of the Lapulapu statue being blamed for the deaths of the mayors was widespread at that time, said Ahmed Cuizon, a regional director of the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB) and an author of a book on Lapu-Lapu City printed as part of the Cebu Provincial Government’s multi-year project to publish a book on the history on each of Cebu’s component towns and component cities. Cuizon said the first attempt to build a statue was in 1917 but it was only in 1933 that one was actually put up, the first in the country, he said.

“Mythology, superstitious beliefs, traditions have played an integral part in every civilization throughout the world. It is a belief structure of the locals. To some extent, locals may find mythology as a way of connecting and continuing history,” said Professor Laila Labajo, chair of the Department of Anthropology, Sociology, and History of the University of San Carlos.

Labajo said the story of the statue and “its tone on death/bad omen and pagsumpa is a typical belief in Philippine society. What makes it historical is the oral tradition or oral history attached to it.”

The lack of historical records on what happened to Lapulapu after the Battle of Mactan spurs many people to “fill in the blanks” with myths and legends, said Cuizon.

But only a few people remember the story of the statue now. Today it stands guard near parked cars of people attending church services in the nearby church. Cuizon said the younger generation no longer remembers the story of the statue and would express amazement when told about it.

He said this shows the huge potential of creating a tour of the old Opon town center to highlight the statue and the other historic places and buildings nearby.

“Whether we like it or not, it (people blaming the statue for the deaths of the mayors) really happened. It’s now part of history,” Cuizon said.

Today, it’s almost easy to miss out the Lapulapu statue in its namesake city when one ventures out to see it. In contrast to the much-celebrated statue in Mactan usually populated by tourists taking photos, the one in Lapulapu City seems almost forgotten.

When I went out to check it after it was recently refurbished, I saw sidewalk vendors selling green mangoes, dried shrimp paste, and some candles, as it is just near the parish of Virgen de Regla parish, who is the patroness of Lapulapu.

I have been taking photographs of the statue for a few minutes already when a curious male bystander took off from smoking in a corner, approached me, and asked, “Kinsa diay na, kuya?” (Who is he?)