From the frontlines: A contact tracer’s story

Here’s what happens to your data and how your info can help beat COVID, according to a contact tracer.

When COVID-19 hit and travel bans and lockdowns were declared, Mhiyaco Tenorio a cruise ship bar waiter, found himself landlocked. “At around August 2020, I read that they were looking for people to join the contact tracers of the Department of Inter ior and Local Government (DILG), so I signed up.”

He was interviewed online and was one of the 150 who received callbacks out of the 900 applicants. Tenorio, who was able to reach third year as a Psychology student at the Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Muntinlupa, also has a medical background as a nursing aide student at the Perpetual Help Medical Center in Las Pinas.

“At first, I just wanted to have something to do, but when I got on board, I learned so many things,” he shares. He is a team leader among the contact tracers of Barangay Sucat in Muntinlupa City.

The training was virtual, modules were given, and an exam was held. At their orientation, aside from familiarizing them with the process of contact tracing, they were also cautioned to be prepared for the worst things that can happen on the job.

“That worst thing happened to me already. To lose a patient that you were monitoring. You give them so much care and attention, but in the end mamamatay din pala,” he sighs. “Ang dami ko nang namatay na patients.”

On the beat

“Our scope of work is to respond, detect, report, isolate and treat. In Barangay Sucat, there are 14 contact tracers allotted. We are in the field most of the time to assist in swabbing patients or looking for those who have been reported as COVID-positive but gave the wrong information.”

Contact tracing for those with incomplete or incorrect information goes through several channels. They coordinate with the assigned physician at the Sucat Health Center and the Barangay Health Emergency Response Teams or BHERT.

“As a contact tracer, we are not under the barangay but under the DILG, we are just assigned to work together with the City Health Office. We work with the BHERT because they are the ones who are more familiar with the territory and they have connections with the community,” he explains.

There are different ways of finding the COVID patients. “The first way is through the LGU. We have a COVID hotline in Muntinlupa, and these are the people who self-report. It then becomes our job to find them. The City Health Office also receives reports of those who tested positive and are from Muntinlupa. Even if you are tested in another location, as long as you give your address as Muntinlupa, you are tagged in our city.”

For the contact of these positive patients, there are what he calls “tiers.” The first tier contacts are the immediate family or household members. After that, they look into the workplace, and find those who have been in a conversation with the patient for more than 15 minutes without social distancing. These are now subject for swab tests, which is free in Muntinlupa.

The third tier are those who are close contacts of their close contacts. “For every patient, you can get up to 32 contacts,” he says.

Truth be told

When we go into an establishment, we fill up contact tracing forms either manually or via contact tracing apps.

The former method was seen as clunky and ambiguous. A restaurateur who requested anonymity says that they really had no clear guidance on the implementation of the logbook. “I’m not entirely sure that there were specific requirements, we just had to copy what the mall was doing—asking people to give their name, address, phone number, and temperature. Everyone later on started doing QR codes and forms on Google sheets. We did that pretty fast. But since not everyone has QR capability, we still needed to have manual logs.”

He also reveals that their logbooks were never checked nor collected. “We expected them to collect it only when there were reports, thankfully we got no actual reports, thus we never needed to be contacted.”

When contact tracing apps were launched last year, restaurants and other establishments shifted to it immediately. Amy Uy of Davao Tuna Grill with branches at the food courts of SM, Robinsons Malls, Shangri-La Plaza, Gateway, Landmark, Market Market and Fisher Mall, says, “When the malls came up with the contact tracing kiosks where you flash your QR code with your personal details on, we didn’t know anymore how the data was handled or used. I believe this was a DILG directive and malls were asked to ensure compliance by all tenants.”

The anonymous restaurateur adds, “The good thing about the StaySafePH app was it reduced the time anyone had to log in their details to as little as 10 seconds compared to 4 to 5 minutes on Google sheets. As a restaurant, it is our every intention to not inconvenience our guests at any point of the meal, including before entering the door. StaysafePH was a great upgrade from the Google sheets. The great thing about it is that if a customer uses it for the first time, they automatically make an account for the guest, so if they happen to be regulars, the next time, the process is even faster.”

Tenorio says that the StaySafePH app was instrumental in tracking where mass transmission may have occurred. They were able to close down a supermarket in the area for disinfection because they were able to track through the app that a lot of positive cases originated from there.

However, not everyone is truthful in their forms. “For dine-in customers, we actually require them to show proof of filling up the contact tracing form before the server can take any orders. This means if they try to fake their details, the server may not take their orders. When we did this, almost everyone started to follow.”

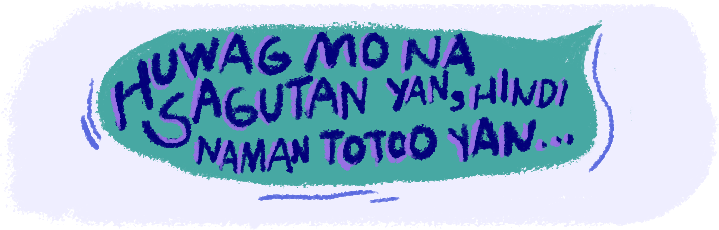

Tenorio is also very strict when he encounters these individuals. “I was once in line at a drugstore, and there was a couple ahead of me. The lady was filling it out properly but her husband says, ‘Huwag mo na i-fill-up yan, hindi naman totoo yan.’ I accosted him and told him that there are many people who have already died, and that he has to take COVID seriously.”

Strength in numbers

Contact Tracing czar Gen. Benjamin Magalong admitted last March 30 that contact tracing in the country was worsening. He explained that for many areas, it does not go beyond the household of the detected COVID-19 case, while ideally in urban settings, the contact tracing ratio should be between 1:30 and 1:37.

In a presentation, he noted the lack of uniform data collection tool among LGUs. The COVID KAYA and Tanod Kontra COVID projects are ineffective, the lack of trained contact tracers, the problems in encoding data, contact tracing analytical tools are not used by many LGUs, and many LGUs do not coordinate with uniformed personnel for contact tracing. He also said that the Stay Safe contact tracing application is not yet in full use, and has not been fully acquired by the government.

As of March 18, DILG Undersecretary and Spokesperson Jonathan Malaya says the NCR has a total of 9,386 contact tracers organized in 2,130 contact tracing teams (CTTs). As of March, there were 29,611 contact tracing teams nationwide.

Each CTT is composed of the Municipal/City Health Officer with members from the Philippine National Police, Bureau of Fire Protection, Barangay Health Emergency Response Teams (BHERTS), volunteers from Civil Society Organizations (CSOs), and the augmentation CTs from the DILG. To expand the program, the Department of Labor through the MMDA has announced last April 11 that they will also hire 14,000 additional contact tracers for Metro Manila.

Cooperation needed

Breaking the chain of transmission is also a community effort, and this is why the DILG and DOH have also launched the “BIDA ang may Disiplina: Solusyon sa COVID-19” advocacy campaign, with DILG Secretary Eduardo M. Año encouraging people participation in the battle against COVID-19 by living a life of discipline and earnestly practicing the minimum health standards.

Tenorio agrees that fighting community transmission is everyone’s responsibility. “Our success rate was better before. Now people don’t believe in COVID anymore or take it lightly. There is a mentality that has become a roadblock for us contact tracers. When we call them, they say they are just home when that isn’t true. There are people who keep going out when they are already positive. We had one case where a patient even went to a drinking session and the whole neighborhood caught COVID.”

He tells stories of families who were all quarantined for 14 days without a source of income. “Sometimes I have to give out from my own pocket because you see the children crying because they have no milk. When they got better, I was really happy that I teared up.”

The satisfaction from his job outweighs the risks, he says. “I am not afraid for myself, but I am afraid to bring the virus home. I take extra precautions, such as sending them all upstairs when I arrive and I strip down to my underwear in our garage. I don’t care if the neighbour sees me,” he laughs.

“When I grow old, I want to be able to tell my grandkids I was on the frontlines of COVID-19, and in my own little way, naging bayani ako.”

Banner illustration by Eka Ypil