The truth about vaccines: How community doctors are combatting vaccine hesitancy

“Measles Area - Regalado - IFC insertion.” I let out a deep sigh under my face mask upon seeing these words on my to-do list. The task was simple: insert an indwelling foley catheter into Patient Regalado located in the “measles area.”

But what it really entailed was me going to a supposed isolation area (read: a corner in the emergency room) where a plethora of parents and their kids sick with the measles virus is being crammed into. Then I needed to find the patient amidst the chaos. Is he that one on the stretcher bed near the fan? Or the one sat beside him, sharing the bed intended for one? How do I perform this sensitive procedure on him with all these other people around?

This was four years ago during the 2019 measles outbreak in the Philippines. Patients—children—with various complications from this highly infectious disease kept coming in. I was a medical student assigned to the Pediatric Emergency Department of a big public hospital in Metro Manila. I felt powerless despite our actively treating them. All the medication felt like desperate attempts and last-ditch efforts to manage what should have been a vaccine-preventable disease.

To me, our health system already failed these patients the moment they got sick.

As with all systemic problems, the outbreak did not happen overnight, but years prior: in 2016, when the number of children who properly got immunized with the measles vaccine declined from 92% to 80%; and in 2017, at the height of the Dengvaxia controversy when mistrust and disinformation were rampant. In 2018, the national vaccine coverage further dropped to 75%. As a result, we fought the largest measles outbreak in the World Health Organization Western Pacific region.

“While the decision-makers at the top are setting the foundations, we are here at the grassroots doing the dirty work, building the people’s trust back in our public health system.”

How do we stop this from happening again? Our interventions should also begin years prior, and they must go deep into the roots of the problem. In 2019, the Universal Health Care Bill was signed into law. In 2020, the Department of Health created the Health Promotion Bureau. In 2021, the Health Promotion Framework Strategy 2030 - Healthy Pilipinas was crafted. In 2022 and 2023, nationwide simultaneous vaccination activities were done. These solutions approach vaccine hesitancy systemically: ensuring that there are public policies supportive of the correct and healthy behavior (i.e. getting vaccinated); that communities make vaccinating an easy and smooth process; and that the people are consistently guided to choose the healthy option.

Now it is up to us health workers in the frontlines to carry out these initiatives. While the decision-makers at the top are setting the foundations, we are here at the grassroots doing the dirty work, building the people’s trust back in our public health system. Barangay health workers, being members of their own community, are instrumental to this trust-building process. They are now enjoined to be Bakuna Champions, community-based volunteers who are social mobilizers advocating for immunization. This aims to bridge the local health system down to the farthest and most isolated parts of the community.

Getting to the fringes of the community is not enough. To cultivate trust, we must listen to the people’s perceptions and understand their motivations; they must feel heard and understood. From responding to their initial hesitations to monitoring for post-injection side effects, there are conversations to be had to genuinely meet them where they are.

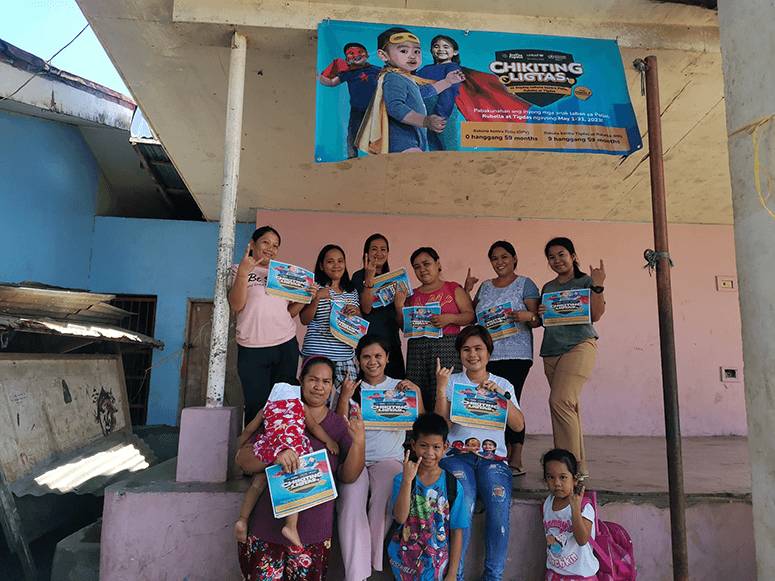

Conveying a clear and consistent message and engaging influential people in the community also helps build trust. To spread awareness for the Measles, Rubella, and Polio Vaccine Supplemental Immunization Activity last May 2023, we, the Rural Health Unit of San Sebastian, Samar, joined the Chikiting Ligtas Dance Challenge and blasted it everywhere. It used the same song containing the same message the DOH wants to convey to the entire country. We also invited the Municipal Mayor’s 4-year-old son to be the first one to get vaccinated. Then for Pinas Lakas: COVID-19 booster vaccination, the mayor got his booster shot in front of his constituents at the launching event. For the community to witness their local leaders support the vaccination programs is a powerful statement.

Combatting vaccine hesitancy is more than just bombarding people with health information. It is the entire pursuit of enabling the people to process that information themselves and letting them choose the healthy behavior naturally. In the recently concluded Chikiting Ligtas: Measles, Rubella, and Polio Vaccine Supplemental Immunization Activity, 111.3% of our target population agreed to get vaccinated. This put the Municipality of San Sebastian, Samar in the top four in the entire Eastern Visayas region for the highest vaccination coverage in the 100-2,000 target population category. That is a significant number of parents and their children who are not just protected from the consequences of another measles outbreak, but now also empowered community partners in health.

“Witnessing the tireless efforts of our nurses, midwives, allied and public health workers, RHU staff, and barangay health workers in the community make this a meaningful pursuit.”

The small successes in this fight serve as empowerment for us health workers in the community. We realize that here at the frontlines, we can do more. We are not anymore confined to the four corners of the hospital running at overcapacity during a surge because we see the larger battle at the grassroots. And witnessing the tireless efforts of our nurses, midwives, allied and public health workers, RHU staff, and barangay health workers in the community make this a meaningful pursuit.