Remembering Chito Sta. Romana

On the morning of August 21, 1971, Chito and I landed in Red China. For Filipino travelers, it was a verboten destination. There were no formal diplomatic relations between the Philippines and China then. In fact, it was illegal to travel there. Philippine passports were stamped with a warning: “Not valid for travel to China, the Soviet Union and other communist-controlled states.”

We were there anyway, 15 youth leaders privileged to visit a country still isolated and poorly understood by the rest of the world. Among us were leftist students, including some of the shock troops of the First Quarter Storm like Ericson Baculinao, the formidable chair of the University of the Philippines’ Student Council.

His counterpart from La Salle, Chito Sta. Romana, was himself impressive. He was especially eloquent. I remember first hearing him speak at a UP auditorium as spokesman of the Movement for a Democratic Philippines, and having nearly every student there convinced that "national democracy" was good for the Philippines.

Chito and Eric would become a huge part of my life. But I knew nothing of this then. Then, we were just guests of the China Friendship Association, a quasi-government agency; then, we were just college students excited about a special three-week study tour. We never expected a lifetime's friendship in the works.

.jpg)

Chito was our delegation leader. He was tall, charismatic, and well-spoken. He was the perfect flag-bearer and spokesman. I remember we arrived at the Beijing airport at night and, as our delegation head, Chito was first to disembark. Chinese hosts waited on the tarmac to welcome us. Unexpectedly, a middle-aged woman walked up to Chito and, in impeccable Filipino, said: “Kayo po ba ang delegasyon ng kabataang Pilipino?” Caught off guard, Chito replied in very crisp English: “Yes!”

For days Chito got a ribbing from us. Inggliserong La Sallista kasi, eh! He was a sport about it, laughing with us every time we recalled the incident.

A few days before we left for China via Hong Kong, I had asked Chito to come home with me to Malolos for a special mission. I wanted my parents to meet him. I wanted them reassured that ours was a legitimate study tour and that their 20-year-old son would be safe in the very mysterious, very vast China. Chito was the perfect person to do it. My parents liked the personable La Sallite.

In the first few days of our visit, we were oblivious to what was going on in the Philippines. China then was totally isolated. There were no direct phone links, no foreign newspapers, no daily radio-TV reports, certainly no mobile phones, Internet, and social media. It was a kind of hermit land.

On the night of August 21, we would learn later, grenade blasts had ripped through an election rally at Plaza Miranda, killing six in the crowd and seriously wounding more, including top leaders of the Liberal Party, which had the strongest chance of unseating then President Ferdinand Marcos.

That same night, Marcos declared a state of emergency and suspended the Writ of Habeas Corpus, allowing his police force to arrest and detain anyone without going through the courts, and lock them up indefinitely. Arrests followed. Many among them were student activists. Those they could not find, they put on a blacklist, and this included some of us in the tour group.

Five of us ended up staying put. “Wait until further notice,” our lawyers in the Philippines advised. A year later, however, on September 21, 1972, Marcos declared martial law—spawning more arrests. Some were tortured; others, kidnapped, adding to the country's desaparecidos. Another year later, our Philippine passports expired. Five of us—Chito, Eric Baculinao, Rey Tiquia, Grace Punongbayan, and I—were now stranded in China.

Forced exile

It was a terrible realization. To know we could not go home without facing jail. To know we were young and fired up about serving country, of being part of big changes. For months, we walked around feeling out of sorts, displaced. We found ourselves stranded in a totally alien landscape, a complex language, and very defined rules and traditions of a proud civilization.

Our Chinese hosts tried their best to make our lives bearable—they offered to continue covering our food and lodging—but they could not help us with the loneliness and the homesickness.

Chito and I shared many lonely nights thinking of our loved ones back home and wondering what to do next. We nearly punished ourselves imagining comrades fighting in the frontlines back home. We spoke of regrets. We had forgone a life that, even if imperfect, allowed for free thought, association, spontaneity—the singing and the dancing, the wit and the jokes, the eating, the street life, the magic of beaches and sunsets—all this was ours back home. Well, it was, until Marcos set himself up as dictator.

Being abruptly stranded in China was brutal but coping with infinite uncertainty was worse. We kept telling ourselves “maybe next week,” then “well, maybe next month.” Winter turned to spring and spring to summer. We went from one frustration to the next.

Struggling with these, Chito and I, with our fellow exiles, propped up each other: “We are much younger than Marcos. We shall outlive him.” (And we did.)

We could have gone home sooner. Some three years into our forced exile, when Imelda Marcos visited Beijing, we received feelers through her Chinese hosts that she wanted to bring us home. Chito and our group thought the offer through, but quickly figured out the agenda of the dictator's wife: she would bring us home as political trophies. We rebuffed the offer.

We asked to work and earn our keep. Our hosts said yes, you may go to the countryside and learn from the working people, just like the millions of Chinese youths are doing. It was part of the “settle down in the countryside” campaign that Mao pushed midway through the Cultural Revolution. In December of 1971, Chito, Eric, Rey, and I went to a state farm in Hengyang, Hunan Province. We worked on the farm for several months.

Manual labor

Like most in our group, Chito was not used to manual labor. I wasn’t. But in the spirit of “remolding our (non-proletarian) outlook” and “learning from the masses,” we spent months working on a state farm in Hunan Province, Mao’s hometown.

In the first several weeks, Chito and I had a really tough time. After all, we were city-bred petty bourgeois boys. Now we were doing wearying, mind-numbing tasks: repairing roads and ditches with crude tools and implements, hoeing dried-up rice fields, replanting rice seedlings, repelling leeches lurking in the water of the fields. We fed pigs, dug canals, picked tea leaves and fruit, all in the spirit of “remolding our bourgeois outlook.”

Perhaps the most wearying: carrying on our shoulders a bamboo pole hooked on both ends with big wooden buckets filled with human waste we collected from public latrines. This was fertilizer for the vegetable plots we tended. It was tough keeping my balance as I walked on uneven dirt paths. It was even harder for Chito, who was nearly six-feet tall. But Chito soldiered on, struggling, slipping, never complaining. I actually heard him humming a tune in between huffs and puffs.

We joked that this was probably what the Filipino song, the one that went "magtanim ay di biro," meant exactly. “Simple living and hard struggle,“ Mao’s revolutionary slogan, became our mantra.

The simple had become important. And, to survive exile, we did away with the negative. We became more philosophical—seeing the exile as interrupting our youth and stealing our dreams, true, but also as opening new paths.

We looked at our exile life as a rare opportunity to understand China up close. We tried to understand the ongoing Cultural Revolution, Mao’s policies and their impact on people’s daily lives and on geopolitics.

Soon, we realized that if we were to survive an indefinite stay in China, we had to learn Mandarin Chinese. In October 1974, we enrolled at the Beijing Languages Institute. It’s the best school for foreign students to learn Mandarin.

We struggled with Chinese grammar and specially with tones: 妈 mā (mother, mom), 麻 má (hemp, numb), 马 mã (horse) , 骂 mà (curse, swear), 吗 mä (particle at end of question.) Each character had to be pronounced with a specific tone to differentiate it from other word with the same or similar sound.

The pictographs were even more complicated. We had to memorize them, stroke by stroke, character by character. We started with 请喝茶 qing he cha (“please have some tea”) and 请坐& qing zuo (“take a seat”). Later we could read the People’s Daily and simple short stories and converse with friends!

Chito mastered Mandarin, dived deep into China’s history and kept abreast with its current state of affairs. He knew China inside out. With those credentials he carved out a successful career as a foreign correspondent in China, a China scholar, and finally a distinguished diplomat and public servant.

Chito did well in our Mandarin class. He got excellent grades in oral and written classes. He used it in his research, initially on economics, his field of interest and training, and later branched out into politics, current events and international relations.

Against all those odds, we have turned a bad thing into a good thing.

Chito mastered Mandarin, dived deep into China’s history and kept abreast with its current state of affairs. He made many friends and kept a rolodex of Chinese contacts. He learned how things worked in China—and why. He knew China inside out. With those credentials he carved out a successful career as a foreign correspondent in China, a China scholar, and finally a distinguished diplomat and public servant.

An economist by training, Chito nimbly branched into politics and international relations. He worked as a researcher for the Washington Post Beijing bureau. In 1987, he enrolled at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy in Massachusetts, earning an MA in international relations. In 1989, he returned to Beijing in time to cover the Tiananmen protests and crackdown for ABC News, the American news network. As ABC producer and later its Beijing bureau chief, he led the network’s coverage of landmark events, including the Wenquan earthquake and the Summer Olympics. He worked with the network's star anchors, Peter Jennings and Dianne Sawyer, when they reported on China. Behind the camera, Chito was the heart of all their coverage.

Chito excelled at his job, something that the Emmys recognized with nominations and awards. And yet, as often as I found myself with him, I hardly ever heard him speak of these accolades. Instead, he just stepped up his China reporting, despite the risks (state censorship) and frustrations (red tape). He was collegial to peers, even to competitors. He mentored young reporters, interns, and Chinese news assistants. He was good for the profession.

After retiring from journalism in 2010, Chito returned to Manila. He taught at the Asian Center of the University of the Philippines. And he co-founded—at one point serving as president—the Philippine Association of China Studies, a non-profit and non-partisan group of China scholars seeking to promote understanding between the now-superpower China and its neighbor, the Philippines.

As accomplished as he was as a journalist and as a professor, Chito seemed born to be a diplomat. He could speak his case without antagonizing other parties. He could get into an argument without raising his voice or digging into words that hurt. I’ve seen him work a room of strangers and charm them. He had the gift of making every person feel like he—or she—were the only person he wanted to address at the time. Even in casual talk, he would look you in the eye, smile, nod attentively. He sometimes kept this eye contact going even when he was behind the wheel. Fearing an accident, I would typically look straight ahead at the road, chatting with him while avoiding his eyes.

He was a consummate conversationalist. Whether it was “natdem," the "Cultural Revolution,” the “Four Cardinal Principles of Socialism,” or “diplomatic hedging strategy,” Chito could always offer explainers. He was good at talking but even better at listening. He could be friends with people he disagreed with. Couple that with his lack of prejudice, his avoidance of negative chatter about others—and you had a consummate diplomat.

Interrupted retirement

Indeed, in 2016, Chito was appointed Philippine ambassador to China. We joked that his easy charm may have played a part, but we knew it was his extraordinary knowledge of China that clinched the job. Yet I knew that accepting the appointment had not been easy for him. He had turned 70, retired, and at home looking after his wife Nancy, bedridden since a stroke in 2015. Chito had to make extraordinary arrangements to even begin to consider the offer: making certain Nancy received the meticulous care she needed; creating an environment supportive of his two adult sons, Norman and Christopher.

He knew, of course, that no one wanted the posting. “It’s a tough job,” he told me in a chat soon after he became ambassador. Two previous career ambassadors, both in their early seventies, had to cut short their tenure after they fell ill under the stresses of the job. Philippine-China relations had been in the doldrums since 2013, when President Benigno Aquino III filed an arbitration suit against China on the territorial dispute over the West Philippine Sea.

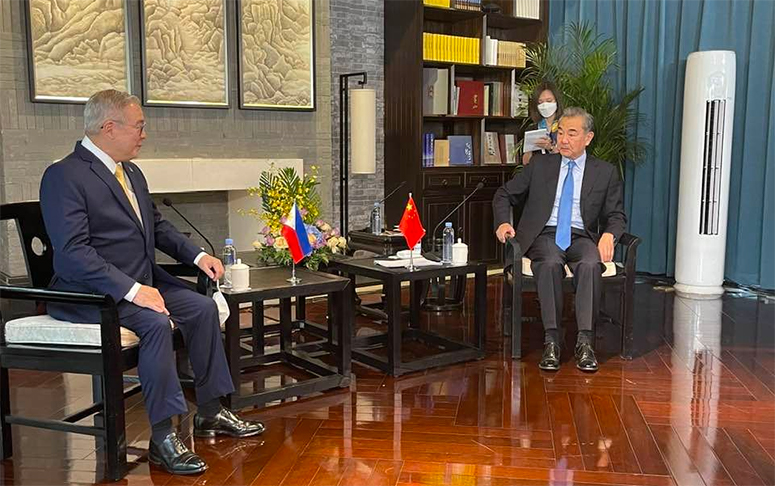

By 2016, relations had plunged into deep freeze after the Permanent Court of Arbitration at the Hague ruled in Manila’s favor, with Beijing refusing to accept the judgment. But in the end, seeing this as a moment to serve people and country, Chito took the job. By then, he had no need for an official Chinese interpreter even for top-level government talks. He knew China’s history and politics, culture and sensitivities, backward and forward. When he took up the post of Philippine ambassador to China, he was perfectly ready.

To me, Chito will always be bigger than the sum of his accomplishments and gifts. He was, I always say, a good man. A good man loyal to his country, people, family and friends.

A former student activist was sick and needing financial assistance? He would be first to suggest we pool money to help. A friend has died? He would have the lot of us buy a wreath. There's a reunion of classmates and activists of old? He would be there, eager to catch up. When my wife Ana got very sick with the alpha strain of Covid in April 2021, Chito was promptly texting her: “Wishing you a quick recovery! Take good care.” A few seconds later adding: “Ingat din Jimi. Take care & stay safe.” These moments may seem small, but to Ana and I, they meant the world.

And Chito had his quirks, too. (Which, truth to tell, I liked. It made him human.) His food loyalties were legendary. Our regular Sunday brunch was coming up? We had visitors to entertain in Beijing? When he could choose the venue, he always went for the Wangshunge Fish Head Restaurant because it served fish head as big as a platter paired with baked pancakes. He also always ordered a plate of fried frog legs.

Equally legendary were his curiosities. He was like a small boy, eyes all lit up, asking a visiting friend about Pinoy showbiz and actually remembering the names of the stars. His was a curiosity about everything. And it erased any arrogance that may have attached itself to someone so accomplished.

Chito was also Mr. Clean. There never was a whiff of suspicion in his decisions and dealings. The higher he rose, the higher the temptation, I gather. He would've been approached by “brokers” asking that he endorse their businesses and by "entrepreneurs" looking to make money out of embassy projects. Chito stayed clear of them.

Intimate bond

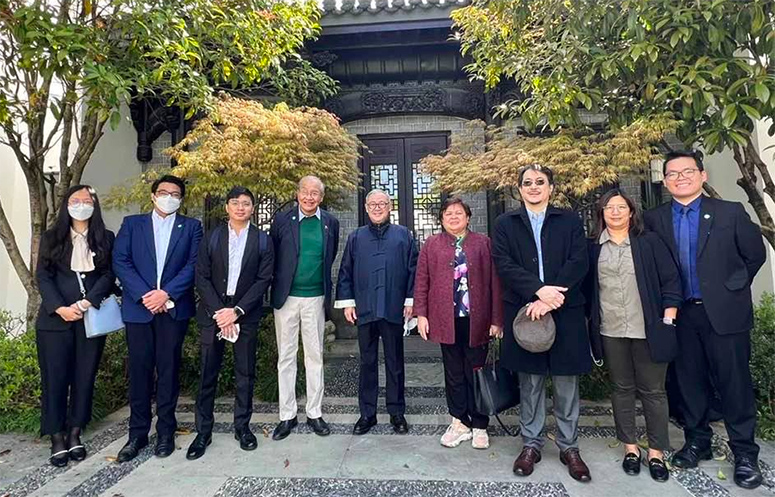

Brought together by exile, Chito, Eric, and I have kept close. That bond has been intimate and something we brought into the lives of our families. Since the 1980s, when we all lived and worked in Beijing, our families traditionally gathered for Sunday brunch. Our children, now living in different cities in the world, still remain their own special friends.

A month before he died, Chito invited me and Ana to have brunch, a tradition we’ve kept for 30 years. He was briefly back in Manila for work consultation. He was looking forward to wrapping up his tenure, he said, with that broad smile that almost made his eyes disappear. He ordered a meal of yoghurt, bread, slices of fruit. He was keen to return to Manila, go back to his interrupted retirement, and personally look after his wife. He planned to fly home on July 1, when a new administration takes over. I was happy for him. He was ending his career on a high note.

As our envoy to China the past six years, Chito had steered the floundering bilateral ties into a robust, multifaceted relationship. Thanks to his knowledge of China and his even-keeled temperament, he handled even the prickliest problems well. The Department of Foreign Affairs recognized his value. “Under his distinguished tenure,” the DFA said in announcing his death, “Philippine-China relations flourished despite differences.”

Chito summed up his patriotism in SERVE, a book to be published by our group of College Editors Guild alumni. “There have been numerous milestones and achievements during my diplomatic assignment,” he wrote in his chapter. “But if there is one thing that I am proud of, it is this: to have played a frontline role in building a bridge of friendship and cooperation between the Filipino and Chinese people that transcended any differences and contributed to regional stability and prosperity. For, after all, what is diplomacy for, if not to serve the people and promote the country’s interests?”

Through the years until his last days, Chito selflessly served our country and people. Always, he proudly waved the Philippine flag.

I am proud of Chito. I will miss him.