Swiss artist and hotelier Patrick Manthe wants to turn Boracay into an art hub

David Hockney’s large canvases were a pain to do, the British artist once said. You can climb up a ladder to paint but you can’t step back to assess your work or you’d fall.

Swiss hotelier and artist Patrick Manthe has experienced that feeling of falling many times over when he steps back to assess his work. In the light of day, contrasts that looked so good the night before under artificial light fall flat on the canvas by morning. It’s almost like what Hemingway said of Africa, that what is true at first light can become a lie at noon.

With one canvas he had been working on for four months, he got so frustrated he painted over the entire thing. He could not stand to look at it, so he erased it completely with a layer of paint to start again from scratch.

It was, for sure, an act of bravery to completely destroy one’s work, but it was also a human need—his own need to start again on something that is so true even the slightest detail would be enough to fill up the viewer’s life in that one moment of viewing.

There was no regret in erasing it, Patrick says, just relief.

It might be unwise to start a story about creating art with how the artist destroys it, but there is, on the opposite side of it, the act of stepping back and saying, “I’m done.”

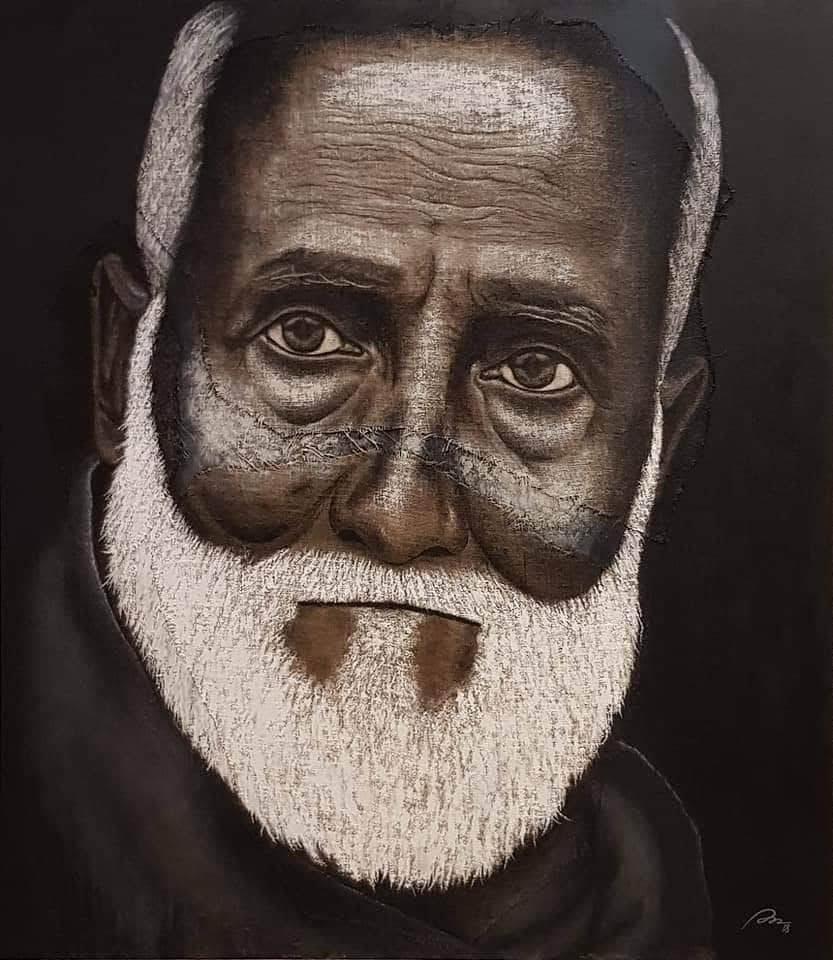

“Entrenched Wisdom” Photos courtesy of Patrick Manthe

Painting portraits is a passion that carries a heavy load. It’s borrowed momentousness from stock pictures of strangers that the process feels like it’s stolen time for both artist and subject.

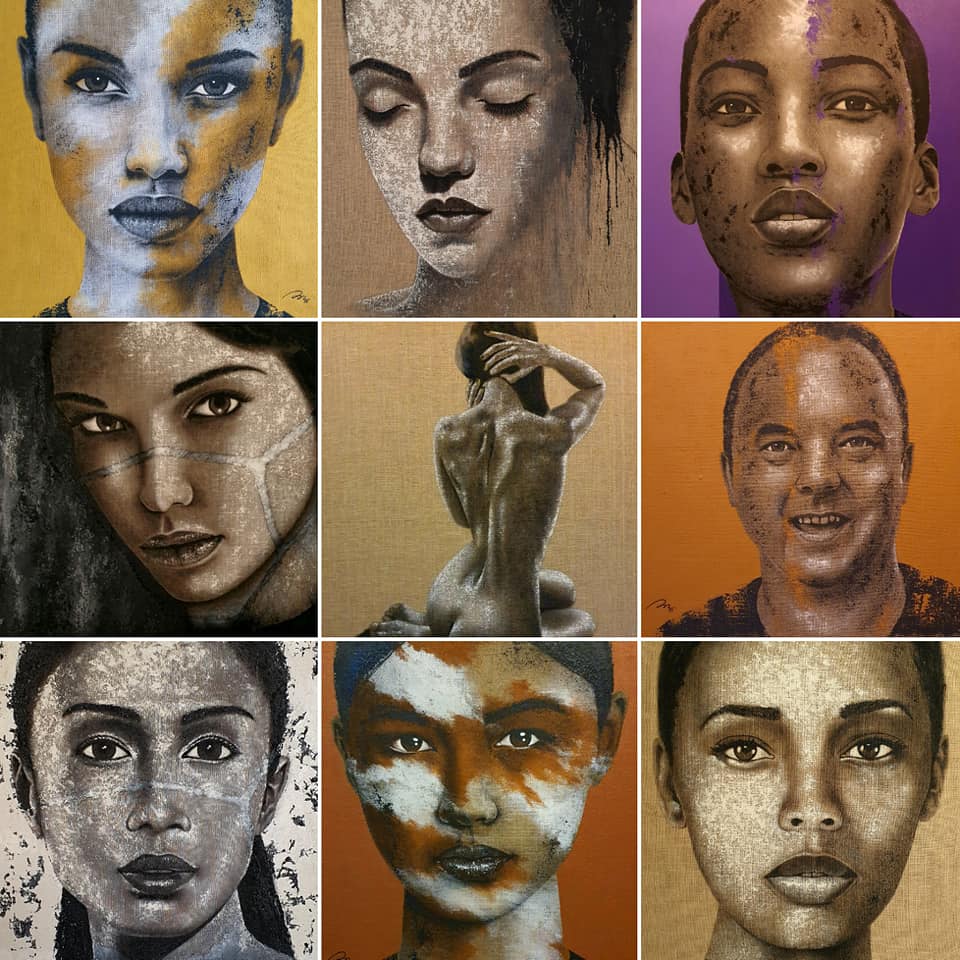

He doesn’t know his subjects, has never met them. Not the girl in the slums that looks with wanting eyes or the beautiful woman that looks obliquely at the viewer, or the old man with barely hidden tragedy in his face.

Patrick’s portraits elicit emotional reactions with their textures, their eyes, the wild yellow or white paint splashed across their cheeks to highlight their imperfections, the lines on their faces. Patrick may say he hates details but those that he puts on his canvas elicit such a visceral reaction.

We walk through crowded life thinking no one is seeing us as we should be seen, but we are seen—under different lights, in different ways. Sometimes we are unrecognizable even or most especially to ourselves. Artists like Patrick see something through the layers of subterfuge we build around us and he paints furiously to get through these layers.

We walk through crowded life thinking no one is seeing us as we should be seen, but we are seen—under different lights, in different ways.

Like the bearded man in “Entrenched Wisdom” with eyes that have seen grief, the young black boy’s innocent gaze that both separates and ages him, the beautiful Chinese woman that opens doors to deep, dark secrets. You can imagine him splashing paint on the canvas to embellish, to make humanity crawl toward a more reachable form of beauty.

He never paints smiling faces because he doesn’t like singular emotions like happiness or sadness. “I find it boring because it doesn’t leave enough freedom for the audience to interact with the portrait,” he says.

He once put five people in front of his canvas at River City in Bangkok—a shopping complex that houses antique shops and galleries—and said, “Tell me what you think about it.” He got five completely different interpretations of his portrait.

People to him are cast in shadows and the light, and his portraits are an eternal rendition of a fleeting moment. All his canvases are large scale with the smallest measuring more than a meter in length and width.

The general manager of Crimson Resort and Spa Boracay, Patrick worked in Bangkok, Vietnam, Australia, Maldives and Europe before the Philippines.

“Art helps me equalize what’s important. You know work is important but actually it’s not everything, there’s another world out there. When I was in Bangkok, I would get home from the hotel around 9 p.m. when my son was about to sleep. I’d paint until midnight. That’s healthy because you’re not getting too far into the work and you can’t mess up too much before you stop.”

The artist has a permanent room in a gallery at River City, Bangkok

At night, he underpaints; during the day, he gets his colors right.

“In the beginning, it’s raw, it’s two-dimensional because you’re doing the outline and then you start shading so you do the first layer, then the third and fourth layers. In my case, from light to getting the areas darker, and suddenly it’s molding out the features, and then it becomes three-dimensional.

“I love that moment. My wife looks at it and says, ‘Did she talk to you already?’ Not yet. But sometimes when I wake up it’s there, and I know it’s going to be a great painting.”

Architecture, art, hospitality

Patrick started as an architectural draftsman in his hometown Chur, the oldest town in Switzerland, located on the right bank of the river Rhine.

His father was an accountant for a bank and his mother early on was a hairdresser.

“My father was a baker and pastry chef in Germany. He came to Switzerland and worked as a bartender, he met my mother and they fell in love. But my mother’s dad said, ‘You can only marry her if you don’t work in hospitality.’ So he had to go to school again.”

When Patrick wanted to leave architecture as a young man and go to hotel school because he wanted travel the world, he was terrified of his father’s reaction. His father had helped him get a job in an architectural firm where he renovated the local bank and theater. Architecture would have been the natural progression of his childhood scribbling (“I was drawing everything!”), but he hated academics and wanted to get out of Chur.

When Anne Curtis was in Boracay in March, Crimson held a competition among local artists. She couldn’t decide on a single winner and in the end she bought all their works. Artists Jap Avelino and Patrick Manthe with their portraits of the actress.

“I thought he was going to rip my head off, but he was like, ‘Wow, that’s great!’ My relationship with my dad changed a lot when I started to travel, he was probably living vicariously through me. ‘Where to next?’ he would always ask and then google everything.”

His mother, on the other hand, wanted him to stay close by. After he completed his higher diploma in hotel management at Swiss School Hotel and Tourism Management, he first worked in Zurich and Germany, then he crossed the Atlantic to work in Australia and the Maldives. He worked for global chains like Hilton, Conrad and Movenpick. When he transferred from Hanoi to Hoi An in Vietnam, he began working for local hospitality companies.

After his contract ended in Bangkok, Patrick was hired by Filipino company Chroma Hospitality to be the preopening general manager of Crimson Koh Samui as it expands abroad.

“I really love to do preopening because my background is architecture and I like to be around construction. In a preopening, you can build your own team, you don’t walk into a team that is already there, which sometimes might not be your style. And of course, you see the whole product coming to life. Apart from the hardware, you can work on the software, on the services, the activities you want.”

Filinvest, the holding company of Chroma, was poised to buy the beachfront property, but then the pandemic happened.

That’s exactly what I want to achieve—that people come back and they’re not just remembering the sunsets, the pool, the food, there has to be another layer. I’ve always felt that from the very beginning when I went into hospitality.

Patrick was transferred to Crimson Boracay in September 2020. While Crimson opened in February 2018, Boracay was closed for rehabilitation from April to October. Its only full year of operations was 2019 because for most of 2020 and 2021, Boracay was at varying levels of lockdown.

That Patrick now helms Crimson Boracay is perfect timing for the resort to create its own identity and for him to bring his passion for art into his work.

On an island like Boracay, where hedonistic pursuits find outlets easily, art is hardly one of them. But he believes the island will benefit from the arts.

“When I first came here, I made a proper presentation to the owners. I love this resort, I love the vibe, the architecture. When the product is good, the beach is nice, the services are great—to me that’s still just a normal hotel.

“That’s when I started to propose, why don’t we make it a creative hub? Not just for art but for fashion, design, music, any artistic form, and try to differentiate ourselves from the rest. Also, the island is kind of moving away from being a party island. I think that’s what the DOT is also trying to do—to highlight the cultural and local aspects.”

Getting kids—and guests—to paint

In October, Crimson announced its first ever artist in residence, Eric Egualada, who handles on-site painting classes and art-related workshops for guests, local residents and staff members.

In November, it launched the ARTS in Youth initiative and sponsored several young students in their artistic education. Four young artists were mentored by Eric and their works were exhibited in the resort.

“Art needs to be only for one person. You may have to find that one person if you want to sell it, but there will be one person in the world for whom no matter what you paint, your painting is exactly for them,” says Patrick Manthe

Patrick also launched "Art On a Plate," which fuses art, music, food and wine with Eric and pianist RJ Pineda; and "Sip and Paint," where guests learn to paint while enjoying wine.

In the latter session that I attended, Patrick himself was the teacher. It was a relaxed afternoon, he was a great teacher, and people discovered artistic inclinations they never knew they had.

“Maybe the wine helped,” he says humbly.

One of the “students” called him up when she got back to Manila and said, “Patrick, I was crying that night because I finally found an outlet to let it all out. This helped me so much.”

“That’s exactly what I want to achieve,” he says. “That people come back and they’re not just remembering the sunsets, the pool, the food—there has to be another layer. I’ve always felt that from the very beginning when I went into hospitality. You have this, but of course you have to deliver in other areas as well. I don’t do anything that doesn’t make money.”

Patrick says Crimson was the first company that encouraged him to infuse art programs into a property and he’s very happy about it.

“If something fulfills you, that’s really all you need.”