Diagnosis: Trump

To hear Mary L. Trump tell it, her family troubles with powerful uncle Donald may have started over a bowl of mashed potatoes.

In her book about growing up Trump, Too Much and Never Enough, the niece of the US president shares a key incident that may have forever soured Donald’s relationship with his older brother, Freddy Trump (her father), at an early age. It happened back when the Trump kids were having family dinner. Donald, the second oldest boy at age seven, was mercilessly picking on his younger brother Robert — until big brother Freddy decided to end it by reaching for the nearest available object on the table, a bowl of mashed potatoes, and dumping it over Donald’s head.

Mary recalls sitting down with newly installed President Donald Trump in the Oval Office after his inauguration ceremony in 2016, the siblings and family gleefully retelling that childhood incident, all of them laughing together. All except Donald, that is; he sat with his arms stiffly crossed. It was no laughing matter to him.

Donald Trump apparently never forgets a slight or jest aimed at him. Just as President Barack Obama cracking jokes about Donald during a White House Correspondents Dinner may have lit his fire to run for president and ultimately burn down every program created under Obama, Trump clearly never forgot about that bowl of mashed potatoes. Mary reports that, the night her father lay dying in a hospital bed after succumbing to a heart attack, other Trump family members sat by the phone waiting for updates on his condition, which proved fatal. Donald was noticeably absent, though; he went to see a movie instead.

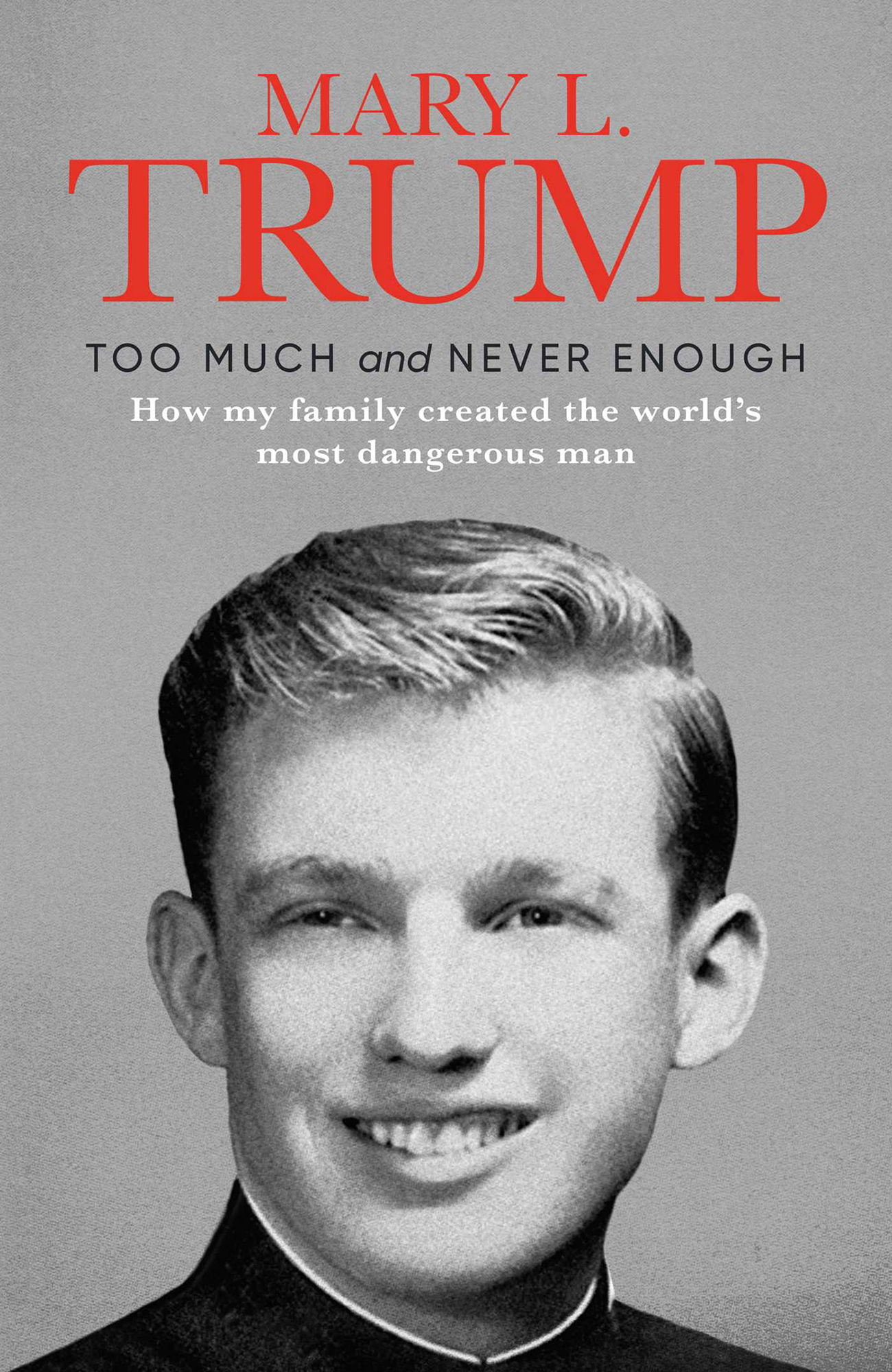

There’s been an endless line of Trump tell-alls since The Donald was elected president in 2016, but Too Much and Never Enough might be the most devastating. While Michael Wolff’s Fire and Fury and Bob Woodward’s Fear capture fly-on-the-wall glimpses of Trumpworld from inside the White House, and John Bolton’s memoir went deeper into Oval Office policy, this one goes inside the actual Trump home. There, Trump’s niece Mary, daughter of Freddy, who was apparently driven to despair, alcoholism and death for not living up to “Trump” expectations, bares all. And it’s a lot to unload.

Many have done armchair analysis of Trump. Mary has some added credentials: she holds a PhD in clinical psychology from the Derner Institute of Advanced Psychological Studies, so she may feel especially qualified to take a peek inside her Uncle Donald’s psyche. She describes him as meeting “all nine criteria” under the DSM’s definition of narcissistic personality disorder, but says that’s just scratching the surface. We’re taken not just inside the Trump house, but inside Trump’s head, reaching back to a father, Fred Trump, who had little interest in his children and thought of every relationship as transactional. And from Mary Trump’s account, the fruit doesn’t fall far from the tree. (For his part, Donald Trump now claims Mary “hardly knew” his family, his father, or mother.)

In truth, oldest son Freddy was considered a natural to take over Fred’s booming apartment-building empire in Queens, New York — largely built on low-interest loans he finagled from Federal (taxpayer) funds. When Freddy balked, saying he’d rather be a commercial pilot for TWA, the Trump patriarch embarked on a campaign to systematically belittle, bully and eventually cut him off from the family wealth. And Donald, the second son, who possessed a precocious level of cruelty, entitlement and toxic positivity, was more than willing to join in, if only to win over his father’s approval.

So it’s classic family dynamics, as rendered through the diagnostic prism of Dr. Mary Trump. Two male siblings jockeying for favor in a father’s indifferent light. Donald was determined to become the “killer” that his dad could respect. In order to get into a good college, Wharton, he allegedly paid another student to take his SAT college entrance exams, and Mary even names the kid who allegedly took them — Joe Shapiro — though admits there’s no physical “proof” the incident ever took place, just family lore.

The bigger “killer” move was when the Trump kids banded together, right after Freddy died, to cut out Mary, her brother and mother from the Trump fortune. The four surviving Trump kids carved out $170 million each between themselves from Fred’s business, while eldest son Freddy was effectively erased from existence. No wonder she’s bitter.

Mary has lots of gossip to unload here, and she is quite angry — after her father died at age 42, her mother and two kids were effectively ghettoized in a shabby Queens apartment, while Donald and Ivana would swan around in limos during Christmas holidays, dropping by to unload some “regifts”: usually something baffling and useless from Ivana, like a single cellophane-wrapped gold lamé slipper filled with hard candy, or a leather daily journal two years out of date for her younger brother Fritz.

But it goes deeper. And more personal. By the end of the memoir, she lays out why she believes Donald Trump is not simply an oversized bully with an oversized ego who somehow managed to game the media into constantly supplying him with headlines, and somehow convinced a large number of voters that “he alone” knew how to solve their problems; he’s actually in way over his head, and so when actual crises hit the country — such as the coronavirus epidemic or the economic implosion — he can only revert to his default setting, which is to never admit mistakes, and find someone else to blame.

The cult of denial of failure was so strong that everyone — especially Fred Trump — had to continue enabling Donald as he developed more grandiose real estate schemes in Manhattan, lost huge sums opening casinos in New Jersey, and careened toward multiple bankruptcies. The millions continued to flow from Fred Trump to back Donald’s teetering empire. It’s as though nobody ever thought of saying “no” to him. As Mary writes, “Nobody has failed upward as consistently and spectacularly as the ostensible leader of the shrinking free world.”

She describes her uncle as being “institutionalized” throughout his life, sheltered from the realities of the world. And by denying him any responsibility, Mary believes, the Trump clan may have built something close to a Frankenstein monster.

Unfortunately for Donald and everybody else on this planet, those behaviors became hardened into personality traits because once Fred started paying attention to his loud and difficult second son, he came to value them. Put another way, Fred Trump came to validate, encourage, and champion the things about Donald that rendered him essentially unlovable and that were in part the direct result of Fred’s abuse.

The fact is, Donald’s pathologies are so complex and his behaviors so often inexplicable that coming up with an accurate and comprehensive diagnosis would require a full battery of psychological and neuropsychological tests that he’ll never sit for. At this point, we can’t evaluate his day-to-day functioning because he is, in the West Wing, essentially institutionalized. Donald has been institutionalized for most of his adult life, so there is no way to know how he would thrive, or even survive, on his own in the real world.

That’s a pretty stark and brutal assessment of the world’s most powerful leader, let alone your own uncle. Mary Trump’s book — despite efforts by the White House to squelch its existence — does offer some resonant glimpses of Donald Trump’s behaviors. But, like the narcissist diagnosis, it only goes so far.

The problem with any analysis of Donald Trump that rests only on psychology is it doesn’t explain the real underlying, nagging question: Why people would vote for him in such large numbers, why they would be taken in again and again by such demonstrable lies and empty boasting, and why his behavior has not been significantly checked by all the remedies available under the US Constitution.