Back to the future home

Cleaning my architecture scrapbook files of 1950s design recently, I came across an article on the Pasay home of noted architect Pablo Antonio Sr. The feature highlighted mid-century modernist trends in residential design, adapted to the Philippine setting.

A good number of aspects of its design are relevant to us today, especially for a future where we need to prepare for all eventualities. We need to learn from the lessons of our lockdown this past year and a half — yes, it has been that long ago that we started on this path.

I had visited this home several times since the 1980s, when I bought a car from Pablo Antonio Jr. and had to pick it up at the Antonio compound. The location of the home near the corner of EDSA and Taft had seen better days. The district was, in fact, an enclave of the well-to-do, due to its proximity to Central Manila, as well as to exclusive schools like La Salle and St. Scholastica’s. From the 1960s however, there was migration to Makati’s modern, suburban “villages.”

The Antonio home is actually a compound that has evolved over a few decades, but with most of the original house and gardens intact. It was designed and completed in the late 1940s.

We need to go back to the past to bring lessons for our future. The pandemic has taught us the importance of gardens and greenery, which was essential to residential design in the 1950s.

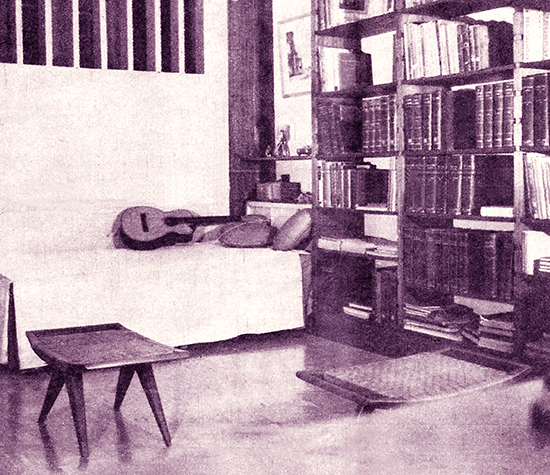

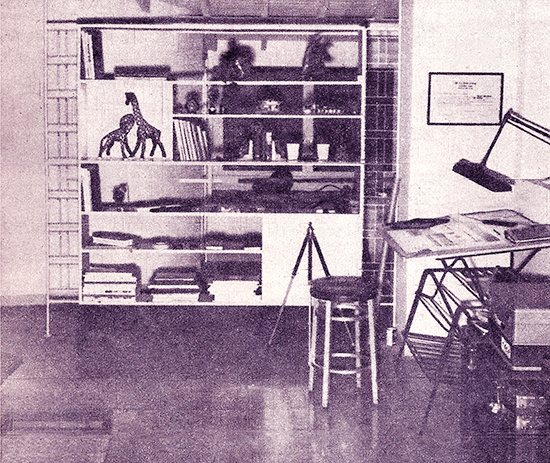

In the 1950s it was often the subject of magazine features. The images accompanying this piece are from 1959 and show how well kept the home was in its first decade of use.

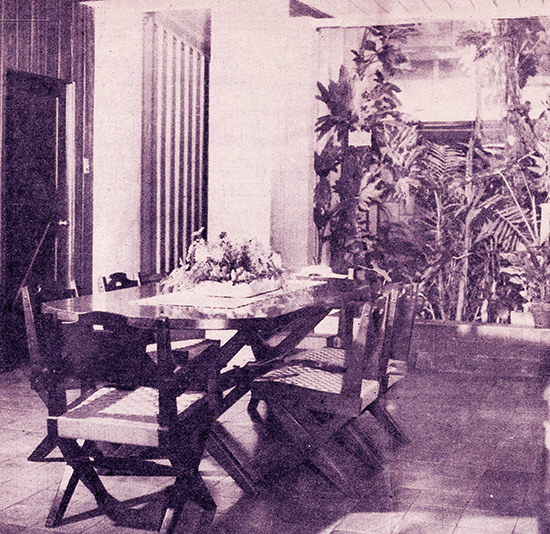

I quote freely from the original article: “A natural coolness pervades the entire house of the Pablo Antonios, a kind of coolness that hits you pleasantly all around, from the entrance foyer to the back parts of the house. This refreshing atmosphere is not attributable to any artificial device like air conditioning (which is absent) but to the effective blending of the outdoors with its interiors through the right combination of good architectural planning and landscape gardening.”

Continuing, “Built in (1949) the residence of the Pablo Antonios, a woody retreat not far removed from the hustle and bustle of the (shopping district) of Pasay City, is a low-slung, ground-hugging T-shaped affair of slanting roofs, set in the midst of a sylvan landscape, a walled-in area abounding in greenery reminiscent of the hilly countryside.

Design features like extra-wide, screened, slanting bay windows admitting the greatest possible view of the outdoors coupled with lush gardens, both indoors and out (the latter attended to personally by Mrs. Marina Reyes-Antonio herself), have achieved a successful fusion of interiors and gardens. The all-around restful coolness thus engendered has the most refreshing effect on both body and spirit, making the Pablo Antonio house a real haven of a home.”

I found out later in my research on the work of Pablo Antonio that he knew and collaborated with the American landscape architect and city planner Louis Croft. Croft had come to the country right before the Second World War to work as a consultant to President Manuel L. Quezon in establishing a system of national parks following the US model. He survived the war despite being incarcerated with his wife and daughter at the UST internment camp.

After liberation, Croft was assigned as city planning consultant to the new national government in the master planning of Quezon City and rehabilitation of Manila. Croft also took private commissions. He would work with Antonio on the design of the new Manila Polo Club in Makati about the same time as this house was built. The main building of the Polo Club has some similarities in detailing and use of adobe as the house. It also was probably Croft’s influence that ensured such a good combination of architecture and landscape design for this residence.

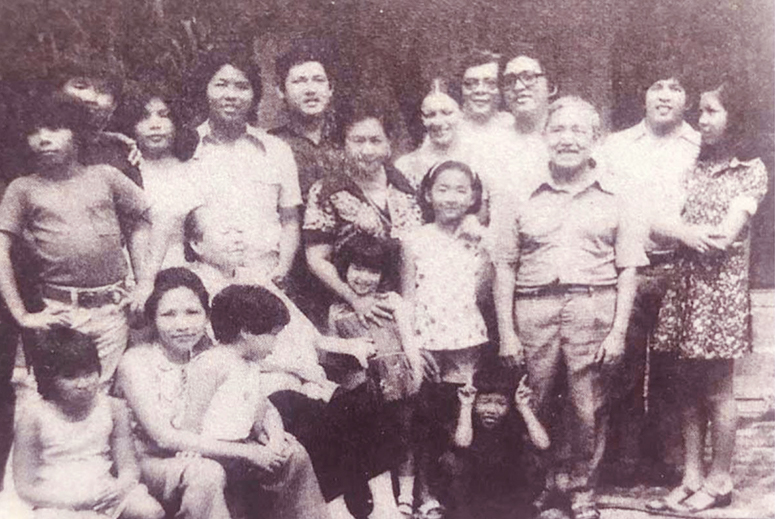

I would revisit the house a few more times in the 2000s as a guest of Mrs. Antonio, as she was in the midst then of putting together a book on her husband and his work. I always enjoyed her hospitality and the experience of the place. It is a testimony to the original design’s robustness, as well as the tender loving care she and the Antonio family have given the home and garden, that ensured its long life.

Residential design has gone through a lot of stylistic changes in the last six decades, but the Antonio house’s climate-sensitive design aligns with current trends to go back to a more sustainable way of building homes. We need to go back to the past to bring lessons for our future. The pandemic has taught us the importance of gardens and greenery, which was essential to residential design in the 1950s.

Moving forward, there are a lot of lessons that can be learned from this 70-year-old home, the most important of which is that we need to take care of our buildings and landscapes, so they, in turn, can take care of us.