The green side of London

My brief encounters with London’s green spaces remain among my fondest memories of the city, from its idyllic public parks and gardens to the intimate communal gardens of residential neighborhoods, and the Chelsea Flower Show, the world’s most prestigious flower show spearheaded by the Royal Horticultural Society.

I went to London in May 1919 to see the RHS Chelsea flower show. The RHS is the UK’s leading gardening charity. Through scientific research and its programs, it aims to make the UK a greener and more beautiful place. The Chelsea Flower Show, as I read, is a place where one can see the latest trends in garden designs, discover new plants, and find ideas to enhance interior or exterior spaces. First opened in 1913, the show has become popular with royals and celebrities, as well as professional and amateur gardeners. Queen Elizabeth II has been an RHS Royal Patron since 1952 and attended the show 50 times during her long reign.

The show site spans 23 acres with more than 500 exhibitors, including show gardens, artisan gardens, and space to grow gardens. The Great Pavilion, which encompasses 12,000 square meters, holds a dazzling display of blooms from the nation’s best nurseries, and growers from around the world. For five days in May, it is estimated that over 150,000 people head to the grounds of the Royal Hospital in Chelsea to attend the show.

On the way to Chelsea from Knightsbridge, I came across shops, hotels, and a private club whose frontages and premises were embellished with stunning floral creations. For those who could not attend the show, the BBC dedicates several hours of coverage for the event.

Arriving at the flower show, we were given a map to find our way around the immense site. At the Great Pavilion, I found an impressive array of flowers, foliage, and garden ornamentals that said much about the special place nature and all its forms holds in the heart of the British.

A delightful display of gladiolas came in shades ranging from deep red and pale green to butter yellow. Peonies, a garden classic, came in hues of soft pink, magenta, and dark burgundy. Lilies were shown in a rainbow of colors, including light peach, lime green, fiery red-orange, and the delicate blush tones of the Lilium Isabella, which won the RHS President’s Award.

Calla lilies potted in gray jars stood out in bright orange, deep purple, and dark pink. Chrysanthemums were displayed in their different forms, such as the small red petals and green centers of the Corsair and Antigua varieties, and the bright-yellow pompoms named Archie Harrison, after the son of the Duke and Duchess of Sussex.

Further along, there was an artful display of vegetables: leafy greens, root vegetables, cherry tomatoes, sweet peppers, and globe artichokes held in baskets and wood containers.

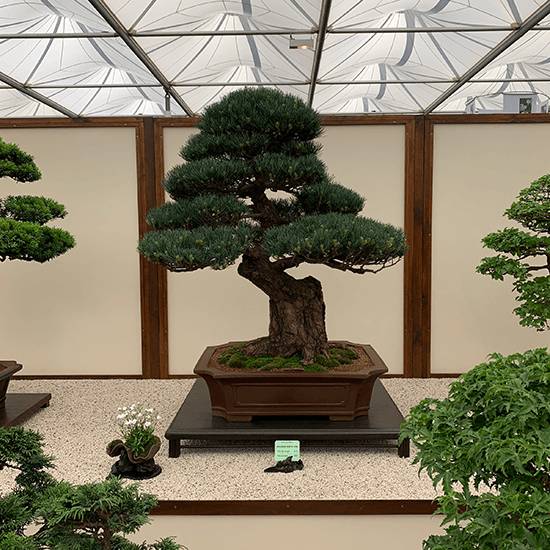

Bonsai trees cut a striking presence in the hall, among them the elegant creeping Juniper, and the distinctive Japanese White Pine with dates of origin that went back to 1958 and 1864, respectively.

Outside the pavilion, I stopped to see some of the show gardens. These conceptual gardens brought particular focus to social and environmental issues. There was a long queue leading to The Back to Nature Garden, which was created by the Duchess of Cambridge with architects Andree Davies and Adam White. It was described by the RHS as “a woodland garden inspired by childhood memories and with families in mind as a retreat from our busy world where visitors could play, learn, discover, and create memories.”

The RHS further pointed out that the garden featured wild trees and shrubs in the color palettes of blue and green. The planting included edible produce, plants for craft activities, and nectar to feed the pollinators. A pathway lined with foliage weaves throughout the garden, around rocks and steppingstones.

Among the flowers in the space were Forget-Me-Nots, a favorite of Princess Diana. These lovely blue flowers with yellow centers are thought ideal for woodland landscapes. Woodland gardens are meant to resemble the wildness of a natural forest.

The Morgan Stanley Garden designed by Chris Beardshaw won the Gold Medal in Chelsea 2019. According to the RHS, it was “inspired by the UK’s love of beautiful gardens and explores how to continue the tradition of creating herbaceous-rich spaces while managing resources more sensitively.” The garden showed how traditional herbaceous borders could be integrated in a contemporary garden setting. The garden was enclosed from behind by an artisan-designed, micro-cement wall. The wall was made using a minimum of micro-materials and was intended to stand the test of time.

The relaxation area at the rear of the garden featured thin stone cladding and laminated timber from sustainably managed forests. Low-voltage lights and the carbon-neutral bamboo decking completed the eco-friendly approach to the design of this garden.

Back at the Great Pavilion stood the eye-catching garden named Floella’s Future. Birmingham City Council’s entry for Chelsea 2019 was designed in partnership with Baroness Floella Benjamin. It touched on four themes, namely: waste reduction, sustainability, clean air, and water conservation. At the center of the display is a three-meter head made of 3,000 tubes, which was shown drinking water from a cup using a plastic straw.

The garden highlights the concern about micro-plastics in the food chain. As explained in the city council’s website, the water brought up through the straw is then recycled into a series of canals representing the 35 miles framing the city. Its pathways are planted with flora, which removes toxins from the air and shows both their beauty and benefits.

For highlighting the urgent need to respond to climate change, the Birmingham City Council won its eighth gold medal at the RHS Chelsea 2019.

Exploring some of London’s parks and gardens—whether you stop at Queen Mary’s Garden to see London’s largest collection of roses; find a peaceful retreat in the Mount Street Gardens of Mayfair amid lush lawns and flowering shrubbery; or stroll around the Dutch formal gardens in Holland Park where walking paths are surrounded by boxwood borders, bright flowers and garden sculptures, it is clear that the city nurtures it green spaces, and cares deeply about them.

Walking around the city, I came across some private, communal gardens—spaces shared by residential neighborhoods—some open to the public occasionally. The Cadogan Place South Garden features black mulberry trees that are about 300 years old, ornamental trees, and well-stocked borders.

At Wilton Crescent Street, a garden fronts an elegant row of Georgian houses. There, modern sculptures stand around tall London Plane trees. For a few moments, I stopped to relish these slices of nature that thrive in a vibrant city filled with endless attractions.

From BBC’s long running program, Gardener’s World, I learned that people in London and right across the country have carved out green spaces within their front yards, backyards, balconies, rooftops, and in the wider community. No matter the size or space, these spots have served as places of refuge, calm, and healing.

Behind the appreciation of gardens and green spaces is the sense of joy that they bring to those who cultivate them, and those who visit them. Gertrude Jekyll, a foremost English landscape architect who is credited with the design of 400 gardens once said, “The lesson I have thoroughly learnt, and that I wish to pass on to others, is to know the enduring happiness that the love of a garden brings.”